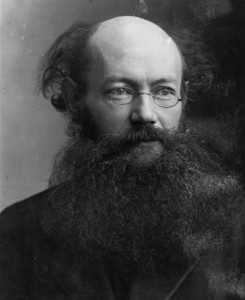

The geographer and anarchist Prince Pyotr Kropotkin first arrived in England in July 1876, fresh from his legendary escape from the Peter and Paul fortress in St Petersburg. He lived briefly in Edinburgh, and earned a living writing for The Times and the journal Nature, but it would be another ten years before he settled in London. His first visit to London was in July 1881 to attend the International Anarchist Congress. Most sources suggest this took place at a pub in Charrington Street, Somers Town (Quail, p. 16) that has been identified in this timeline (p. 37) as the Brewer’s Hall (no longer there, but at no. 59, according to the Dead Pubs website). George Woodcock states that the congress began on 14th July on Charrington Street, and included ‘a fair array of the celebrated names of anarchism. Malatesta and Merlino, Kropotkin and Nicholas Chaikovsky, Louise Michel and Emile Pouget’ (Anarchism, pp. 241-3). However, Stan Shipley notes that ‘The Radical (23 July 1881) reports a congress held on Monday July 18th at the Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy Square, with […] speeches from Marie Le Compte, the transatlantic agitator, Louise Michel, and Kropotkin’ (p. 60).

The geographer and anarchist Prince Pyotr Kropotkin first arrived in England in July 1876, fresh from his legendary escape from the Peter and Paul fortress in St Petersburg. He lived briefly in Edinburgh, and earned a living writing for The Times and the journal Nature, but it would be another ten years before he settled in London. His first visit to London was in July 1881 to attend the International Anarchist Congress. Most sources suggest this took place at a pub in Charrington Street, Somers Town (Quail, p. 16) that has been identified in this timeline (p. 37) as the Brewer’s Hall (no longer there, but at no. 59, according to the Dead Pubs website). George Woodcock states that the congress began on 14th July on Charrington Street, and included ‘a fair array of the celebrated names of anarchism. Malatesta and Merlino, Kropotkin and Nicholas Chaikovsky, Louise Michel and Emile Pouget’ (Anarchism, pp. 241-3). However, Stan Shipley notes that ‘The Radical (23 July 1881) reports a congress held on Monday July 18th at the Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy Square, with […] speeches from Marie Le Compte, the transatlantic agitator, Louise Michel, and Kropotkin’ (p. 60).

Kropotkin moved with his wife Sophie to Islington in October of the same year, and with Chaikovsky was active ‘touring the metropolitan radical clubs to collect money for the Red Cross Society of the People’s Will’ (Shipley, p. 13), to support those imprisoned after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II.

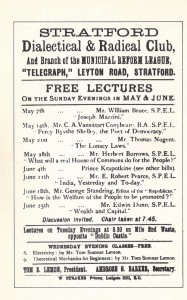

One meeting at which Kropotkin spoke in May 1882, held at the Patriotic Club, Clerkenwell Green (now the Marx Memorial Library), erupted into an argument between George Standring, editor of The Republican, and Charles Murray of the Manhood Suffrage League, over whether this Red Cross was a political or a philanthropic movement. At this meeting Kropotkin also met the young anarchist Ambrose Barker, and accepted his invitation to speak at the Stratford Dialectical and Radical Club (Shipley, p. 36), so this undated handbill (reproduced from Shipley) advertising ‘Prince Krapotkine’s’ [sic] appearance on 4th June must also be from 1882.

One meeting at which Kropotkin spoke in May 1882, held at the Patriotic Club, Clerkenwell Green (now the Marx Memorial Library), erupted into an argument between George Standring, editor of The Republican, and Charles Murray of the Manhood Suffrage League, over whether this Red Cross was a political or a philanthropic movement. At this meeting Kropotkin also met the young anarchist Ambrose Barker, and accepted his invitation to speak at the Stratford Dialectical and Radical Club (Shipley, p. 36), so this undated handbill (reproduced from Shipley) advertising ‘Prince Krapotkine’s’ [sic] appearance on 4th June must also be from 1882.

But despite such activity, Kropotkin’s first stay in London was not a happy experience, and he left a year later, apparently unable to bear the solitude, and declaring in his Memoirs of a Revolutionist ‘Better a French prison than this grave’ (II, 254). And a French prison was indeed where he ended up, following his arrest in December 1882 for belonging to the International Working Men’s Association (the First International).

After his release in January 1886, Kropotkin and his wife arrived back in London in March 1886, staying at first with his fellow exile Sergei Stepniak-Kravchinsky in St John’s Wood. He immediately became involved in political and propaganda activities, stating in his Memoirs, ‘[t]he socialist movement was in full swing, and life in London was no longer the dull, vegetating existence that it had been for me four years before. We settled in a small cottage in Harrow’ (II, 306). Some might see a contradiction between these two sentences, but I couldn’t possibly comment. The attractions of Harrow apparently included the proximity of his old comrade Nikolai Chaikovsky (Morris, p. 60) and a nice garden (both Kropotkin and his wife were keen gardeners). I have not yet been able to establish the precise location of this house.

That first summer in London was a difficult period; Sophie was severely ill with typhus, and Kropotkin received news of his brother’s suicide, shortly before he had been due for release from Siberian exile (George Kennan describes his encounter with Alexander Kropotkin in Siberia and the Exile System, I, 325-33). By October 1886 Kropotkin had written the majority of the first issue of the anarchist-communist monthly journal Freedom, published by Charlotte Wilson, which was the first step to the foundation of the Freedom Press, still located in Whitechapel today. Aside from this, and resuming his scientific journalism, again for The Times and Nature, he also spoke at workers’ and anarchists’ meetings around the country, and met both middle- and working-class anarchists.

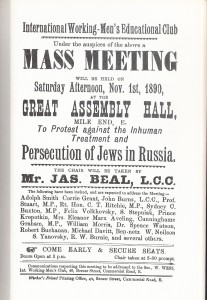

Fishman has a good deal of information on this (pp. 193-268). On 1 November 1890, Kropotkin appeared at a meeting at the Mile End Assembly Hall (site of the Tower Hamlets Mission), alongside Stepniak-Kravchinsky, Feliks Volkhovsky, Eleanor Marx, William Morris and others, to protest against persecution of Jews in Russia (p. 193; handbill reproduced from Fishman). The following year, on 11 November, Kropotkin was one of the speakers at a memorial meeting for the Chicago Martyrs at the South Place Institute (the Ethical Society, which later moved to Conway Hall, Red Lion Square); other speakers included Louise Michel and Errico Malatesta (p. 207). On 7 February 1896, he gave a lecture at the Working Lads’ Institute, 137 Whitechapel Road (p. 218). Particularly notable was the march from Mile End Waste and rally in Hyde Park on 21 June 1903 in protest at the Kishinev pogrom; 25,000 people gathered and Kropotkin, who arrived late, was lifted over the heads of the crowd, giving short speeches in Russian and English despite his illness (p. 252). Advised by his doctor to retire from public speaking, Kropotkin nevertheless contributed to the inaugural ceremony and series of Friday lectures at the workers’s club established in February 1906 at 165 Jubilee Street (p. 265). The building is no longer there.

Fishman has a good deal of information on this (pp. 193-268). On 1 November 1890, Kropotkin appeared at a meeting at the Mile End Assembly Hall (site of the Tower Hamlets Mission), alongside Stepniak-Kravchinsky, Feliks Volkhovsky, Eleanor Marx, William Morris and others, to protest against persecution of Jews in Russia (p. 193; handbill reproduced from Fishman). The following year, on 11 November, Kropotkin was one of the speakers at a memorial meeting for the Chicago Martyrs at the South Place Institute (the Ethical Society, which later moved to Conway Hall, Red Lion Square); other speakers included Louise Michel and Errico Malatesta (p. 207). On 7 February 1896, he gave a lecture at the Working Lads’ Institute, 137 Whitechapel Road (p. 218). Particularly notable was the march from Mile End Waste and rally in Hyde Park on 21 June 1903 in protest at the Kishinev pogrom; 25,000 people gathered and Kropotkin, who arrived late, was lifted over the heads of the crowd, giving short speeches in Russian and English despite his illness (p. 252). Advised by his doctor to retire from public speaking, Kropotkin nevertheless contributed to the inaugural ceremony and series of Friday lectures at the workers’s club established in February 1906 at 165 Jubilee Street (p. 265). The building is no longer there.

But despite these activities and the appreciative reception Kropotkin always seems to have received, he formed the ‘conviction that a revolution was impossible in England’ (Memoirs, II, 312), because the demands the workers were making had not yet reached the level of those of the socialists, and he felt that as a result even the slightest improvements in conditions would be deemed acceptable. But in some quarters Kropotkin was also considered too gradualist; in 1909, Rudolf Rocker had to dissuade a group of young Russians from their plan to assassinate Kropotkin on the grounds that his moderate influence was holding back the revolutionary forces (Fishman, p. 272).

Kropotkin gradually moved from propaganda to intellectual activities, and published a number of his best-known theoretical writings whilst in London, including The Conquest of Bread (1892), Fields, Factories and Workshops (1899), and Mutual Aid (1902), as well as In Russian and French Prisons (1887) and Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1899). But he clearly maintained an important position and was seen as an authority; when Shaul (Saul) Yanovsky, the editor of the Yiddish socialist newspaper Arbeter Fraint, was felt to be damaging the paper because of his authoritarian tendencies, it was Kropotkin who was called in to warn him of the damage he was doing (Fishman, p. 208).

In summer 1894, he and his wife moved to 6 Crescent Road, Bromley (again, the garden was important, and at least it had the advantage of being a remote suburb in South London, rather than North), commemorated with a blue plaque.

This became an open house for anarchist exiles, and British socialists such as Keir Hardie (Morris, p. 69). Life was not easy, though; Fishman notes that it was practically a hand-to-mouth existence, and there was never any money in the house – when Stepniak visited Bromley from Hammersmith, Sophie had to borrow money from the neighbours for his return ticket (p. 222). Nevertheless, he gave financial support to anarchist causes, including donating money to the Arbeter Fraint so that it could continue publishing (Graur, p. 94). Perhaps the most notable incident of his life in Bromley happened in January 1905, when news of the Bloody Sunday massacre in St Petersburg reached Britain. According to his nephew, who was staying with him at the time, the cottage was besieged by reporters who wanted to interview Kropotkin. He was ill at the time, and just sent out a note with ‘Down with the Romanovs!’ written on it (Woodcock and Avakumovic, p. 365), which conjures up a rather marvellous picture.

This period saw increasing numbers of Russian (mostly Jewish) immigrants to the East End, who formed not only the largest Russian emigre group in Europe, but also the largest anarchist group in Britain. With the increase in activity this implied, Kropotkin remained involved despite increasing health problems. He participated in further anarchist conferences in London in December 1904 and October 1906 (Woodcock and Avakumovic, p. 360), and in October 1906, he also helped launch a new periodical, Listki khleb i volia (Pages from Bread and Freedom), the forerunner of which (Bread and Freedom) had been published by young radicals who returned to Russia after the 1905 revolution.

This venture lasted less than a year, but reinforced his contacts within anarchist groups; the journal was printed at 33 Dunstan Houses, Stepney Green, the headquarters of Yiddish anarchism and home of its de-facto leader, Rudolf Rocker (Fishman, p. 268). It was to this magnificent block (built in 1899 and still there in all its glory) that Kropotkin took one one of his visitors, Afanasy Matushenko, one of the leaders of the Potemkin mutiny, in late 1905 (Fishman, p. 258). But he also, in these later years, began to work with the authorities; in 1909, in co-operation with the British parliamentary committee on Russian affairs, he produced the report The Terror in Russia, which had a great impact on British opinion of Russia at the time (Woodcock and Avakumovic, p. 373).

Two years later, Kropotkin and his wife moved to Chesham Street, Kemp Town, Brighton (I do not know which house), which, according to Woodcock and Avakumovic, ‘looked like a dull end to an active life’ (p. 387) — perhaps an odd observation, considering the long years of suburban life. In his later years he became isolated from much of the anarchist movement because he saw the war as necessary to protect France from German absolutism and militarism (Grauer, pp.111-20). Like many Russian exiles, he returned to Russia with his family after the February revolution of 1917, but he was unenthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution. He died in 1921 near Moscow.

Two years later, Kropotkin and his wife moved to Chesham Street, Kemp Town, Brighton (I do not know which house), which, according to Woodcock and Avakumovic, ‘looked like a dull end to an active life’ (p. 387) — perhaps an odd observation, considering the long years of suburban life. In his later years he became isolated from much of the anarchist movement because he saw the war as necessary to protect France from German absolutism and militarism (Grauer, pp.111-20). Like many Russian exiles, he returned to Russia with his family after the February revolution of 1917, but he was unenthusiastic about the Bolshevik revolution. He died in 1921 near Moscow.

Sources

William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals, 1875-1914 (London: Duckworth, 1975)

Mina Graur, An Anarchist ‘Rabbi’: The Life and Teaching of Rudolf Rocker (New York: St Martin’s Press; Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 1997)

James W. Hulse, Revolutionists in London: A Study of Five Unorthodox Socialists (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970)

George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (New York: Century, 1891), 2 vols

P. Kropotkin, Memoirs of a Revolutionist (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1899), vol. 2

Brian Morris, The Anarchist Geographer: An Introduction to the Life of Peter Kropotkin (Minehead: Genge Press, 2007)

John Quail, The Slow Burning Fuse: The Lost History of British Anarchists (London: Flamingo, 1978)

Stan Shipley, Club Life and Socialism in Mid-Victorian London (London: Journeyman/London History Workshop Centre, 1983)

G. M. Stekloff, History of the First International (London: Martin Lawrence, 1928)

George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic, The Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin (London: Boardman & Co., 1950)

George Woodcock, Anarchism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963)

Philip Hines

/ January 12, 2011Thanks for this post. A fascinating character; the combination of anarchism and a liking for suburban gardens must be unique. Can’t help wondering what plants he grew, though; I imagine some cabbages, cucumbers and dill for pickling, among the roses and chrysanths.

Another Stoppard play there somewhere.

Sarah Young

/ January 12, 2011Indeed! In the addendum I’ve just published, Rocker describes Kropotkin in terms of the integrity of his person and his beliefs, so the cabbages and crysanths were as much a part of his make-up as his philosophy. I certainly imagine there would have been a bit of an emphasis on fruit and veg, as the family’s income was pretty meagre.

Andrew Birukov

/ November 28, 2011Замечательная статья! Сходу я не все понял, т.к. английским владею плохо. Постараюсь перевести.

I have a photo of house where Kropotkin lived in London. probably Muswell Hill Rd. May I send it to you for expertise?

Sarah Young

/ December 12, 2011Please do send it – I would love to see it! Do you have a scanned version you can send? If so my email is: sarah [at] sarahjyoung.com

Tom Bombadill

/ January 27, 2012Thanks for this interesting post. I found out about Kropotkin recently, after watching an interview with Chomsky. I intend to read more: anything that challenges justifications for social-Darwinism must be worth a look, particularly now that our profit-driven, individualistically-oriented societies appear to be so challenged. Besides, I was born in Bromley and grew up in Brighton, so Kropotkin seems like my kinda guy!

Tom Bombadill.

Sarah Young

/ January 29, 2012Thanks – Kropotkin’s definitely my kind of guy too!

Chris Hewitson

/ July 13, 2012Kropotkin lived at number 9 Chesham Street in Brighton.

Sarah Young

/ July 13, 2012Thanks!

Douglas Tallack

/ August 10, 2013I have just moved to Bromley and live a few streets from the house where Kropotkin lived. When a student, I also lived in Kemp Town, and knew that he lived there, too. I don’t know much about Bromley’s history but H.G. Wells was born about half a mile away in the town centre and lived there until c1879. A few miles away is Downe House but Darwin had died before Kropotkin moved to Bromley.

Roger Kattenhorn

/ September 17, 2013Hi Sarah,

I was looking for stuff about Mary Bridges Adams who helped Russian exiles in WW1, when I stumbled on your bit about Kropotkin. I see you don’t know where he lived in Harrow. It was 17, Roxborough Rd.

The house was demolished in 1996 but I took a photo and will send it if I can figure out how to. Chaikovsky I believe a couple of streets away in College Rd. I have some scraps of info about his time in Harrow if you’d like. Do you know the story of his court appearance at the Edgware Petty Sessions?

You have a classy looking site by the way.

Best wishes

Roger.

Sarah Young

/ September 19, 2013Hi Roger,

Many thanks for this. I’d love to see the picture, and any other info you have about Chaikovsky (who is close to the top of my ‘to do’ list). I haven’t come across the story of his court appearance, so would be very interested to hear more about that. I assume your material is in hard copy? If you sent it to me, I could scan it and send it back to you. My work address is: Dr sarah Young, SSEES, UCL, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT.

best wishes,

Sarah

Rod Quinn

/ July 6, 2015After his return to Russia did Kropotkin urge the new government to continue its involvement in the First World War?

If he did it would explain his growing isolation from the anarchists and other revolutionaries.

Sarah Young

/ July 7, 2015Good question, but don’t know the answer off hand, will have to look that up.

Roger Kattenhorn

/ August 9, 2015Hi Rod,

Kropotkin certainly did back the Russian Government’s policy of continued involvement in WW1 but he was already quite isolated in the anarchist movement for his support for the war against Germany. In 1914 a distressed comrade, Malatesta, wrote ‘Anarchists Have Forgotten Their Principles’ in response to a pro war manifesto signed by Kropotkin. It also led to a falling out with the editorial staff at the Freedom newspaper he had founded. He nevertheless maintained his public stand of support for the allied war effort, to the point where a young Stalin wrote to Lenin “I have recently read Kropotkin’s articles – the old fool must have completely lost his mind.”

He was pretty much painfully estranged from the anarchist/revolutinary movement by the time he returned to Russia in 1917. He miscalculated the mood of the people in Russia and supported Lvov/Kerensky’s revolutionary government in its policy of continuing the war.

When the Bolshevik coup took place in October he remarked ‘this buries the revolution’ and redeemed himself somewhat within Anarchist circles by condemning their party dictatorship. But the damage was already done and the Bolsheviks used his views on the war to taint the whole anarchist movement in Russia.

Stephanie Calman

/ March 29, 2020Dear Dr Young

I’ve been told my grandfather Calman Israilevitch (d 1950) belonged to a ‘Russian club in the City frequented by Kropotkin’. My gf didn’t arrive until 1912. I don’t think he was an anarchist as such, but is there any institution you know of that might fit this rather meagre description? It doesn’t quite sound like the ones in your excellent article here. I’d be grateful for any reply you can give me.

With Thanks

Stephanie Calman