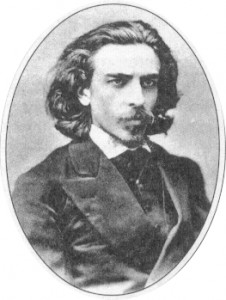

On 11 July 1875, the philosopher and poet Vladimir Solov’ev arrived in London. Having finished his studies (in natural sciences, then history and philology) at Moscow University and at the seminary at Sergiev Posad, Solov’ev was already, at the tender age of 22, teaching philosophy at Moscow University.

On the advice of various friends and colleagues, including Dostoevsky, he travelled to Britain to study Kabbalistic, gnostic and mystical literature, and wasted no time in getting down to work; in a letter to his mother dated 13 July, he reports registering at the reading room of the British Museum on the previous day. Although he made a number of friends in London, mostly with Russians, including the sociologist Maxim Kovalevsky, he spent most of his time alone, working in the library, which he described as ‘the best institution in the world’ in a letter to Pyotr Alekseevich Preobrazhensky dated 7 August 1875.

He immediately moved into lodgings at 39 Great Russell Street (now home to Gosh! comics), where the landlady was one Mrs Siggers. In a letter to Olga Novikova, the notorious right-wing Russian publicist who lived in London for many years and wrote regular articles on Russian affairs for the Pall Mall Gazette, also written on 13 July, he states that his rooms are ‘quite gloomy’, but that he is ‘enjoying seeing the London smog through the open window’. In the light of this, his claim in a letter of 29 July to his mother that ‘London is notable for its fresh air and is the healthiest city in the world’ looks more like an attempt to assuage parental concerns than an honest assessment.

He was, at least, at pains to ensure his parents have the correct address for correspondence. He concludes his letter of 13 July: ‘London. 39 Great Russel [sic] Street, W. (Opposite the British Museum)’, and then spends subsequent letters explaining that he had missed out the ‘C’ and that they had to write W.C.; ‘Russel’ never regains the missing ‘l’, however.

Given his interest in all aspects of mysticism, not only in literature and philosophy, but also its popular forms, it is perhaps not surprising that Solov’ev was attracted to the spiritualists who achieved great notoriety in Britain at the time, encounters he describes in a brief but detailed letter to his friend Dmitry Nikolaevich Tsertelev, dated 3 September 1875. He is not impressed, saying his hopes of finding something interesting were in vain, and his impression was of ‘charlatans on the one hand and blind believers on the other’. He refers to a seance he attended, conducted by ‘Williams’, who is ‘a magician, more impudent than expert’, and whose manifestation of the spirit control popularly known as ‘John King’ (reputedly the spirit of the pirate Henry Morgan) ‘looked as much like a spirit as I do an elephant’. Solov’ev was, I was not surprised to learn, correct; Charles Williams, together with his partner Frank Herne, operating out of 61 Lamb’s Conduit Street, was more than once exposed as a fraud. Solov’ev ends his letter by noting that the following week, Williams, who had been ‘somewhat taken aback by my discoveries [assumedly of the absence of real spirit activity – SJY] last time’ would be holding a ‘test-seance’ (written in English). Solov’ev promises to send more news if anything beyond the expected occurred; the absence of any further reference to the subject speaks for itself.

But this was something of a side-show from his main work in the library, described in the letter to his mother of 29 July as ‘ideal in all respects’. Walicki states (p. 372) that in London Solov’ev studied ‘the history of mysticism, especially the Neoplatonic tradition and German mysticism and theosophy (Jacob Boehme, Franz Baader).’ His work was apparently going well, but was famously interrupted by his vision of Sophia, the personification of divine wisdom. Twenty years later, he described the vision — and the two others he was granted — in the poem Mochul’skii describes as ‘semi-joking’ (p. 69), ‘Three Meetings’:

… My dream took me to the British Museum,

And my dream was no misdirection.

Shall I ever forget that blessed half-year?

Not phantoms of perfect beauty,

Neither lives, nor passions, nor nature —

But You! You owned my whole soul.

Despite the crowd’s bustle back and forth,

And the roar of fire-breathing factories,

Despite the hard city blocks, the soulless buildings —

In sacred silence I sit, here, alone.

Well, certainly cum grano salis:

I was lonely, but no misanthrope;

In social solitude.

Which of my friends shall I now name?

A shame, that in this short space I cannot manage

Their names nor their foreign chatter…

I’ll just list: Two, three British wizards

And, yes, two or three masters from Moscow.

So few so much the better, leaving me alone in the library;

And believe it or not (God is my witness),

Mysterious forces chose my

Every book; and I read only of Her.

When sinful whims whispered,

“Look in a book ‘from another opera’” —

Such operatic dramas erupted,

That in confusion I fled back to my flat.

And it was here — it was autumn —

When I told Her: “Divine Flower,

I feel Your touch! But why have you hidden Yourself

From my sight since I was a boy?”

At the very moment these thoughts moved through my mind —

Instantly, golden azure filled the room,

And she shone before me once again —

But just Her face — Her face.

At that instant lasting bliss was born in me!

Once more my soul went blind to mundane matters.

If I gave a sober hearing to Her, I know not what I heard;

Her words were incomprehensible, talk fit for a fool.

3

I said to Her: “I see your face,

But I yearn for all of you.

What You have not held back from the boy,

That — the young man also wants!”

“To Egypt go!” — a voice within proclaimed.

Translation by Ivan M. Granger. Taken from Poetry Chaikana.

… Моей мечтою был Музей Британский,

И он не обманул моей мечты.

Забуду ль вас, блаженные полгода?

Не призраки минутной красоты,

Не быт людей, не страсти, не природа –

Всей, всей душой одна владела ты.

Пусть там сиюут людские мириады

Под грохот огнедышащих машин,

Пусть зиждутся бездушные громады, –

Святая тишина, я здесь один.

Ну, разумеется, cum grano salis:

Я одинок был, но не мизантроп;

В уединении и люди попадались,

Из коих мне теперь назвать кого б?

Жаль, в свой размер вложить я не сумею

Их имена, не чуждые молвы…

Скажу: два-три британских чудодея

Да два иль три доцента из Москвы.

Всё ж больше я один в читальном зале;

И верьте иль не верьте, – видит Бог,

Что тайные мне силы выбрали

Всё, что о ней читать я только мог.

Когда же прихоти греховные внушали

Мне книгу взять «из оперы другой» –

Такие тут истории бывали,

Что я в смущенье уходил домой.

И вот однажды – к осенью то было –

Я ей сказал: «О божества расцвет!

Ты здесь, я чую, – что же не явила

Себя глазам моим ты о детских лет?»

И только я помыслил это слово, –

Вдруг золотой лазурью всё полно,

И предо мной она сияет снова –

Одно её лицо – оно одно.

И то мгновенье долгим счастьем стало,

К земным делам опять душа слепа,

И если речь «серезный» слух встречала,

Она была невнятна и глупа.

3

Я ей сказал: « Твое лицо явилось,

Но всю тебя хочу я увидать.

Чем для ребёнка ты не поскупилась,

В том – юноше нельзя же отказать!»

«В Египте будь!» – внутри раздался голос.

… And, despite his initial intention of staying in London for at least six months, Solov’ev changed his plans immediately, leaving for Cairo on 28 October 1875. In Egypt, still wearing a long black coat and the silk top hat he found so difficult to get used to in London (letter to his mother, 13 July), he was robbed by the Bedouin in the desert (Mochul’skii, p. 69). But, according to the poem, he was at least granted his third vision.

Sources

Letters to Solov’ev’s mother and D. N. Tsertelev taken from: Vladimir Solov’ev, “Nepodvizhno lish’ solntse liubvi…”: Stikhotvoreniia, Proza, Pis’ma, Vospominaniia sovremennikov, n. ed. (Moscow: Moskovskii rabochii, 1990), pp. 184-190 and 209-10.

Letters to O. A. Novikova and P. A. Preobrazhenskii taken from Vladimir Solov’ev, Pis’ma, ed. E. L. Radlov (Petersburg: Vremia, 1923), pp. 161-2 and 231-2.

Translation of ‘Three Meetings’ by Ivan M. Granger at Poetry Chaikhana.

Konstantin Mochul’skii, Vladimir Solov’ev: Zihzn’ i uchenie (Paris: YMCA Press, 1951)

Andrzej Walicki, A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism, trans. Hilda Andrews-Rusiecka (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1980)