As regular readers will know, I am currently working on a book manuscript on the Russian tradition of prison and exile writing, from the tsarist era to the present day. This is a subject that generally focuses, with good reason, on the victims’ perspective, and many people will disagree with the idea of including Stalinist propaganda in such a study. I was myself reluctant to address works like The History of the Construction of the White Sea Canal (1934), the collectively written volume edited by Maxim Gorky and others, that celebrate the first large-scale Soviet forced labour projects and publicize the theory of reforging (perekovka) through re-education, hard labour and differential rationing depending on the amount of work achieved. I initially began work on this topic because of my interest in Dostoevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead, Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales, Sergei Dovlatov’s The Zone, and the many other fascinating, and frequently harrowing, memoirs and fictional works that make up this tradition. I did not anticipate spending much time reading about the salutary effects of hard labour in works that ignore most of the salient facts, including the arrests of large numbers of people on trumped-up political charges, the shocking mortality rates, the violence and extremely harsh conditions convicts endured, and so on – in other words, almost everything we would normally associate with the Gulag.

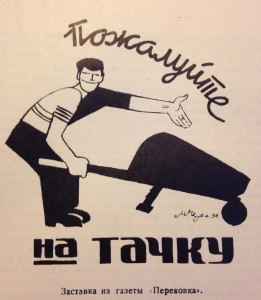

Cartoon from the camp newspaper ‘Perekovka’, Ida Averbakh, Ot prestupleniia k trudu (From Crime to Labour, 1936)

But I became increasing convinced that such works do in fact belong in my project. My subject is precisely the tradition of labour camp writing, and while the majority of texts may take the form of critiques and/or be written by former convicts, books like The History of the Construction of the White Sea Canal make a significant intervention in part because of the counter-perspective they represent. That counter-perspective is also important for the light it sheds on vital questions about the Gulag that underlie its ambivalent legacy and contested memory in Russia today. This is in part because its brutal reality notwithstanding, the Gulag was conceived, theoretically at least, with the aim of transformation of criminals, and it enjoyed popular support for that reason. Moreover, the Gulag as umbrella term encompassed many different types of institution, and incarceration was not a homogenous experience – one only has to read Solzhenitsyn’s In the First Circle to understand that, or recall the many depictions in memoirs of ‘loyalists’ in the camps, who endorsed their own incarceration as contributing to the building of socialism.

So, in addition to The White Sea Canal book, I embarked on studying Nikolai Pogodin’s 1934 ‘comedy’ play about the reforging of criminals on the White Sea Canal project, The Aristocrats, and the 1936 film version directed by Evgeny Chervyakov, The Convicts, documentaries about the White Sea and Moscow-Volga canal projects, pamphlets by an OGPU (secret police) operative about a youth offender commune, and scholarly texts from the 1930s on reform through labour, including Ida Averbakh’s From Crime to Labour. The latter work, which I initially expected to use only as a secondary source, particularly caught my attention. Part turgid Stalinist tract, part coffee-table book, full of pictures of smiling, reformed prisoners and their artworks – there are over 50 pages of illustrations – it represents the most consistent attempt both to place the idea of reform through labour in a Marxist-Leninist framework, and to persuade and attract the reader. All these works had similar aims: there was a huge effort in the first half of the 1930s to present a positive image of corrective labour camps and popularize the idea of reform through physical work. I don’t think this effort should be viewed simply as a cynical attempt to obscure the horrific aspects of the Gulag. While conditions were already very harsh, this was relatively benign phase in the Gulag’s history, and indeed I think it is wrong to suggest that the authorities at this stage felt they had very much to hide. The change in policy from celebration of hard labour to silence that took place at the start of the Great Terror – when conditions deteriorated markedly and the most lethal branches of the Gulag, such as the camps of Kolyma in Russia’s Far East, were established – shows that the Stalinist regime had a far more reliable way of concealing the reality when that became expedient. Rather, these texts and films should be seen as a genuine attempt to communicate a new approach to penal justice, however partial and idealized the picture they paint.

Such important ideological work could only be put in the safest of hands, so it’s no surprise to see Gorky, chief architect of Socialist Realism, at the helm of the White Sea Canal book, alongside Leopold Averbakh, formerly head of the Proletarian Writers’ Union, and a high-profile member of the security services, Semyon Firin, director of the White Sea-Baltic corrective labour camp. Ida Averbakh also had impeccable credentials: a prominent jurist in her own right, she was also the niece of the late Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov, sister of Leopold and wife of the head of OGPU, Genrikh Yagoda (it seems likely in fact that she was responsible for her husband’s rise to power). These backgrounds, as well as the aims of the texts and films, lead one to expect a clear articulation of the socialist basis of the theory of reforging. But beyond the Stalinist jargon and repeated assertions that reforging is socialist, there is little in these works to support that claim. Instead, they use similar strategies to avoid not only depicting the crucial turning points in the transformation of the reforged prisoners, but even reference to the motivating factors, so that the process is divested of both psychological and ideological content. Where a socialist element is apparent, such as the role of the collective, the authors reverse both causality and accepted definitions, so that reforging is distanced from socialism, instead of representing its apex. In my paper for the SSEES Centenary conference, Socialism, Capitalism and the Alternatives: Lessons from Russia and Eastern Europe, I shall explore some of the strategies these works use that undermine the relationship between reforging and socialism. I will examine some alternative – and seemimgly contradictory – sources for the theory of reforging in pre-revolutionary discourses of prison and exile, and discuss the implications of these for our understanding of the Gulag as the essence of Stalinism, and as a necessary part of the Soviet building of socialism.

kate dillon

/ November 10, 2015I have recently uncovered some letters from my great grandmothers husband whilst in the prison of Vologda 1923 or 1928 (the writing is so small).

They are, essentially, love letters but only two. it appears they had a connection with the Russian Refugee’s self help association and the Russian Book Store in London. Please contact me if you would like any information

Sarah Young

/ November 10, 2015Thank you for this – I’d very much like to know more and will be in touch.

M

/ February 18, 2016I’d love to discuss this topic, privately, if possible. I will tell you that Ida was my relative. One of the most poignant examples of Stalin’s maniacal paranoid 1930s purge of the old reds, was regarding Averbakh’s mother, Sophie, imprisoned, as well. She would occasionally get letters from the outside. Her young grandson writes her a heartbreaking missive of one line, the only positive thing he could say, ”Grandmother, I did not die again, today….” I have stories, related to your research, including their disillusionment, revision of beliefs, and experiences.

Sarah Young

/ February 29, 2016Many thanks for this. I’d very much like to discuss this with you. Please email me at sarah[at]sarahjyoung.com.

Sarah