Reading: Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground (1864)

This week we turn to the main response to the Nihilists’ ideas of rational egoism and social reorganization, in the form of Dostoevsky’s 1864 novel, Notes from Underground. Dostoevsky is the only writer whose fictional texts we are examining in any detail, but I think this is justified in a course on intellectual history in part because of the philosophical nature of Dostoevsky’s writing, but also because the literary context of the Nihilists’ writings. The appearance of Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done? in particular, demanded a literary response; as we shall see, the form Dostoevsky’s work takes is an important part of his answer to his opponents’ theories.

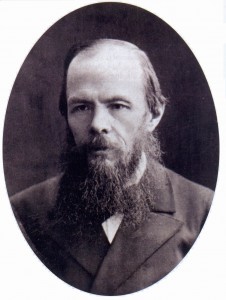

Dostoevsky’s biography is very well known, but I will go over the important elements for those of you who do not know it, and also because I want to emphasize a couple of things in particular (for more details, see Joseph Frank’s five-volume biography, or the one-volume abridged edition, or for a concise work on Dostoevsky’s life, Robert Bird’s recent study is useful). Dostoevsky was born in Moscow in 1821 to a quite religious family from the impoverished nobility. His father was a retired army doctor who worked at a hospital for the poor. He was sent to St Petersburg – the city with which he became so strongly connected – in his teens to study at the military engineering school housed in the Mikhailovskii zamok (where Tsar Paul I had been murdered in 1801) and on graduation joined the engineering department of the war ministry in 1843, but in the following year he resigned his commission in the army and began his literary career.

This, you will remember, was the time when “natural school” aesthetics and social or critical realism were at their most popular (Gogol’s “Overcoat” was published in 1842) and when Belinsky was very much the key figure on the literary scene. His praise for Dostoevsky’s first original literary work, the epistolary novel Poor Folk (1846), about that stock figure the “poor clerk,” oppressed by the Petersburg bureaucracy, turned it into an overnight success. But this was short-lived; Belinsky derided Dostoevsky’s next work, The Double(1846), as a sub-Gogolian fantasy. Indeed Dostoevsky’s works in this early period are of mixed quality, but this not really the point; I mention Belinsky to indicate the overlap of the different generations, and to emphasize the fact that Dostoevsky was moving in similar circles and was very much involved in philosophical debate at the time. (Frank is particularly good on this background.)

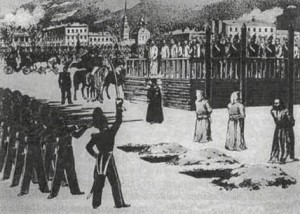

The particular group to which Dostoevsky was connected was the Petrashevsky circle, named after Mikhail Petrashevsky (1821-1866), in whose apartment the group met. Socialist and democratic ideas were very much on the agenda (on their ideas, see Walicki, pp. 152-61), but this was not a particularly extreme group. There were more radical members, notably the off-shoot group surrounding Sergei Durov (1815-1869) and Alexander Palm (1822-1885), who went as far as trying to acquire a printing press – a necessary condition for radical activity – and Dostoevsky was involved with them to some extent. The Petrashevtsy were certainly radical enough to come under suspicion, and in the end they were arrested in late 1848, ostensibly because of Dostoevsky’s reading of Belinsky’s “Letter to Gogol” to the group. Dostoevsky, along with other members, was incarcerated in the Peter and Paul fortress, and eventually sentenced to death.

The group underwent a mock execution in Semenovsky square in Petersburg in November 1849, reprieved moments before they were supposed to be shot, and were sentenced to hard labour instead. Dostoevsky spent four years in a prison camp in Omsk, and then was exiled to Semipalatinsk as a ordinary soldier. He was allowed to return to European Russia at the end of the 1850s and resumed his literary career, his first really notable work being the fictionalized account of his imprisonment, Notes from the House of the Dead (1861).

The experience of the prison camp, and in particular of being incarcerated alongside peasant convicts, unsurprisingly had a profound effect on Dostoevsky, and began what he called the “rebirth of [his] convictions.” This ultimately led to him adopting a very conservative position, praising the Orthodox church (and the autocracy) and seeing the Russian peasantry as a uniquely holy “God-bearing people” that would bring salvation to mankind. His arrival at that worldview was gradual (see Jones, p. 46), and in the early 1860s, when he wrote Notes from Underground, I would contend that it was not fully in place, or, at least, not being expressed in the dogmatic (not to say xenophobic and anti-semitic) form his views took in the 1870s. Relating to this question, there is also a distinction to be made between Dostoevsky’s fiction and his journalistic writings, as it is almost solely in the latter that his most intemperate and ugly pronouncements appear; his fiction very seldom exhibits the same sort of nationalistic tendencies, and one can even say that a quite ambivalent picture of his most sacred beliefs, including the Orthodox church, emerges in his novels. So although he is very frequently nowadays described as an Orthodox Christian novelist, I think this is a limiting definition that does not fully acknowledge the scope of his work (it also makes him sound incredibly dull and worthy, and he is anything but). My own view is that questions of religious faith – like other “accursed questions” – are central to his thinking, but that encompasses all sides of the question, including (perhaps even privileging) doubt and non-belief. In a letter of 1854, shortly after his release from prison, he described himself as “a child of the age, a child of unbelief and doubt,” who would, however, rather “remain with Christ” even if it were shown that Christ lay outside the truth (Dostoevskii, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, 28/1:176). I suspect that sense he had of both the need for an ideal and the uncertainty inherent in living in an age in which God was no longer a given, remained with him throughout his life.

Despite these very significant ambiguities – which are, after all, what make Dostoevsky such a complex and interesting writer – it is true to say that when he arrived back in St Petersburg he was a changed man, and had left his youthful dabbling with socialism way behind him. And the literary and philosophical milieu to which he returned was transformed as well; as I said in my last lecture, a new generation of thinkers had taken over, with much more radical ideas – ideas with which Dostoevsky not only disagreed, but which he found profoundly dangerous. And this is the context in which he wrote Notes from Underground, which can be seen primarily as a response to Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done? and the ideas of rational egoism developed in “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy.” It is also frequently seen as an example of early existentialist philosophy.

The underground man, as the narrator of Dostoevsky’s novel is habitually called, bases his argument on the question of human nature. Contrary to the Nihilists’ view of human nature as rational, because of the absence of dualism they assert, the underground man states that human beings are full of contradictions and dualities, ir-rational, and do not always act for their own benefit:

Oh, tell me who was first to announce, first to proclaim that man does nasty things because he doesn’t know his own true interest; and that if he were enlightened, if his eyes were opened to his true, normal interests, he would stop doing nasty things at once and would immediately become good and noble, because, being so enlightened and understanding his real advantage, he would realise that his own advantage really did lie in the good. […] when was it […] that man has ever acted only in his own self interest. […] And what if it turns out that man’s advantage sometimes not only may, but even must in certain circumstances, consist precisely in his desiring something harmful to himself instead of something advantageous. (Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground, p. 15; pt 1, ch 7; page numbers refer to the Norton Critical Edition, translated by Michael Katz)

He acknowledges that reason is one aspect of human nature (Notes, p. 20), but is far from being all of life, and he suggests that if human beings did always act rationally, and science were able to uncover the laws governing human activity to the extent of being able to define man’s best interest – as Chernyshevsky claimed would happen – man, far from being able to act for the benefit of society as a whole would have no autonomy and therefore no responsibility for his actions:

science itself will teach man […] that he in fact possesses neither a will nor any whim of his own, and that he himself is nothing more than a kind of piano key or an organ stop. […] we need only discover these laws of nature and man will no longer have to answer for his own actions. (Notes, p. 16; pt 1, ch 7)

The underground man, like his rationalist opponent, equates this imaginary situation where everything in human life is accounted for, with the Crystal Palace:

new economic relations will be established, all ready-made, also calculated with mathematical precision, so that all possible questions will disappear in a single instant, simply because all possible answers have been provided. Then the crystal palace will be built. (Notes, p. 16)

So the Crystal Palace becomes a symbol of the rational, utopian future. But the narrator questions this idea of future perfection: won’t it just be ‘terribly boring’, he asks (Notes, p. 16). (It’s interesting that in later works by Dostoevsky, such as Demons, the idea of the ‘anthill’ of social reorganization for the benefit of all mankind leads to slavery; one could suggest that the idea of boredom advanced here is somewhat more subtle.) In Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (written shortly before Notes from Underground, as a response to his first visit to Europe), Dostoevsky characterizes the Crystal Palace as monolithic and unanswerable:

you feel a terrible force that has united all the people here, who come from all over the world, into a single herd; you become aware of a gigantic idea; you feel that here something has already been achieved, that here there is victory and triumph. […] “Hasn’t the ideal in fact been achieved here?” you think. “Isn’t this the ultimate, isn’t it in fact the ‘one fold’? Isn’t it in fact necessary to accept this as the truth fulfilled and grow dumb once and for all?” […] You feel that it would require a great deal of eternal spiritual resistance and denial not to succumb… (Winter Notes, p. 37)

That sense of unanswerability is still present in Notes from Underground: the narrator states that suffering “is inconceivable in the crystal palace; suffering is doubt and negation. What sort of crystal palace would it be if any doubt were allowed?” (p. 25) (I discuss Dostoevsky’s response to the Crystal Palace in more detail here.)

But the underground man does now propose an answer, or rather, two answers, even if he is not sure either is entirely possible in practice. In the face of this rational perfection, you can behave gratuitously, i.e. perform a pointlessly irrational act: you can stick your tongue out (Notes, p. 25). Or you can destroy it – throw stones at it. What is wrong with perfection, he states, is that it leaves people with nothing to do. ‘Man is a creative animal’, he states, ‘destined to strive consciously towards a goal’ (Notes, p. 23), but it is the process rather than the goal itself that attracts man, and he claims man will turn to destruction, even – perhaps especially – of his own creations, rather than fulfil the goal.

Both these possible responses to the Crystal Palace – the randomly gratuitous and the violently destructive – point to the irrational nature the underground man ascribes to man. Far from being happy to accept organized perfection for the benefit of all, he claims,

man, always and everywhere, whoever he is, has preferred to act as he wished and not at all as reason and advantage have dictated; one might even desire something opposed to one’s own advantage, and sometimes […] one positively must do so. (Notes, p. 19)

Why is this so? Because he states that man’s primary interest – what he calls “the most advantageous advantage” (Notes, pp. 16, 19) – is in asserting his personality and individuality, for which ‘a man may intentionally, seriously desire even something harmful to himself, something stupid, even very stupid’ (Notes, p. 21). And this is a question of freedom, of man proving that he is still a man and not a ‘piano key’ (Notes, p. 22), that he is not at the mercy of the laws of nature, and that his will has some meaning.

We could link this idea of freedom, and its opposition to the necessity it ascribes to the Nihilists’ principle of rational egoism, to Khomiakov’s “Iranian” and “Kushite” principles (see Hudspith, pp. 99-101). The importance of freedom to Dostoevsky derives from the perspective he gained in prison, where he sees that the peasant convicts, deprived of their will, will do anything to assert their sense of freedom (see, e.g. Notes, pp. 108-10), even actions that will result in their punishment or which objectively harm them in other ways, in order to show that they retain their individuality, their personality. And this is significant because the Russian peasantry becomes such a moral force in Dostoevsky’s later thinking. So this idea of the necessity of individual freedom is an essential component of Dostoevsky’s moral world.

But Notes from Underground is not quite as simple as that, and this is where its construction as a work of art rather than philosophy comes into play. The first thing to note is that this conception of irrationality and freedom is is being advanced not by Dostoevsky, but by his narrator; Dostoevsky may agree with some of the things the underground man says, but the fact that he has constructed a character to express these ideas should give us pause for thought. Because although we might happily concur with some of the underground man’s pronouncements in part 1 – about man’s irrational side, and the importance of maintaining the freedom to assert one’s own personality – most sane readers would not see his actions or personality in part 2 as any sort of model to emulate (and this is important because the characters in What is to be Done? were perceived precisely in those terms). His life is isolated, as he is unable to build or maintain any meaningful relationships, and he is bitter, spiteful, perverse, sadistic and aggressive – in other words, thoroughly unlikeable, and difficult to sympathize with (indeed, he would not want his reader’s sympathy, and part of the problem is that a lot of his aggression is directed at the reader).

So what does this mean? To what extent does his personality engender his ideas, and does this thereby undermine them? As Vasily Rozanov states:

The man from the underground is a person who has withdrawn deep within himself. He hates life and spitefully criticizes the ideal of the rational utopians on the basis of a precise knowledge of human nature, which he has acquired through a long and lonely observation of himself and of history. (Rozanov, p. 48)

On the one hand, the underground man’s ideas affirm the subjective nature of human experience, which in itself reasserts humanity as dualistic, and rejects the possibility that human beings are knowable. But on the other hand, is his own experience, and knowledge of his own personality, sufficient to develop an all-encompassing theory of human nature? Surely he is not typical; his behaviour is certainly skewed, so should we not also assume his views are? His very isolation implies that he does not understand “normal” people.

So what is the point? The underground man’s polemic in part 1 has been taken in isolation as a complete philosophy, but that only examines half of the story; his memoiristic, confessional text in part 2 is there for a reason, and that must be to shed further light on the ideas of part 1, or to change them in some way. In which case we have to look at his personality and actions in more detail and consider them in relation to his ideas.

The fact that part 1 of the novel begins “I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man” (p. 3) indicates immediately how important the underground man’s personality is. It is evident that he is driven by spite, directed at both himself and others; he would not visit a dentist if he had toothache, out of spite towards himself and a desire to irritate others, proving his irrationality by harming himself and others.

But this aspect of the novel is fully developed in part 2, “A propos of wet snow,” when we see the underground man as he was twenty years ago, before his retreat from the world. In a series of real and aborted encounters – with an officer who has no idea he even exists (for a very good analysis of this scene in relation to What is to be Done?, see Berman, pp. 221-228), his old school acquaintances, and a prostitute – the underground man reveals the full extent of his capacity to harm himself, and thereby act against his own self-interest. We see, for example, how he imposes himself on the school friends who do not like him and whom he does not like, apparently out of sheer perversity, thereby creating a situation that can only result in his own humiliation. But does acting against his own self-interest in this way assert his freedom, and his personality, as his discourse claims? It appears not; far from proving his freedom, these irrational acts become necessary. As examples of this, we can point to the fact that he tells himself he will not be late for the dinner, but is then – inevitably – the first to arrive, or the way he rejects Liza the prostitute, when she offers him the chance of happiness and a way out of his isolation. In such circumstances there is only one way he can logically act: irrationally, and self-damagingly. So the underground man becomes trapped in a vicious circle, and is forced to act against his own self-interest, thereby showing not his freedom, but his non-freedom. Moreover, the fact that his irrationality is the product of his logic also indicates the trap he has created for himself, and that he is not as irrational as he thinks (or, perhaps, would like us to think). As Joseph Frank states, his ideas

do not arise, as has been commonly thought, because of his rejection of reason; on the contrary, they result from his acceptance of all the implications of reason in its then-current Russian incarnation – and particularly, all those consequences that advocates of reason such as Chernyshevsky blithely chose to disregard. (Frank, p. 416)

Beyond implying that the application of reason may not – contra Chernyshevsky – lead to actions for the benefit of all, and beyond the underground man’s own perception (whether erroneous or misleading) of his irrationality, another aspect of the question of whether he is able to act freely relates to his interactions with others in a different way. Unable to relate to others properly in part 2, he consciously rejects human contact and isolates himself in the ‘underground’ (as we see in part 1). But in neither part of the novel does he actually prove capable of managing without another person. His notes are supposedly written for himself alone, with no public audience in mind, and yet he constantly addresses (and tries to provoke) his readers (“that’s something you probably won’t understand”, p. 3), and polemicizes with the “gentlemen” who are evidently those people who follow the precepts of rational egoism (“after all, two times two makes four is no longer life, gentlemen but the beginning of death”, p. 24). And in part 2 we see this even more acutely at the dinner party; the narrator describes the scene thus:

I smiled contemptuously and paced up and down the other side of the room, directly behind the sofa, along the wall from the table to the stove and back again. I wanted to show them with all my might that I could get along without them; meanwhile, I deliberately stomped my boots, thumping my heels. But all this was in vain. They paid me no attention. I had the forebearance to pace like that, right in front of them, from eight o’clock until eleven […] It was impossible to humiliate myself more shamelessly and more willingly, and I fully understood that, fully; nevertheless I continued to pace from the table to the stove and back again. “Oh, if you only knew what thoughts and feelings I’m capable of, and how cultured I really am!” I thought at moments […] But my enemies behaved as if I weren’t even in the room. Once, and only once, they turned to me, precisely when Zverkov started talking about Shakespeare, and I suddenly burst into contemptuous laughter. I snorted so affectedly and repulsively that they broke off their conversation immediately and stared at me in silence for about two minutes, in earnest, without laughing, as I paced up and down, from the table to the stove, while I paid not the slightest bit of attention to them. But nothing came of it; they didn’t speak to me. (Notes, pp. 55-56)

The paradox he finds himself in is quite apparent here: he wants to manage without the other, or perhaps even more than this to demonstrate his ability to manage without the other, and yet that only works if the other pays attention to the fact that he is ignoring them, i.e. he in fact needs the other to affirm his own stance (see Bakhtin, pp. 227-36 on this process). So he cannot remain in isolation from the world and assert his own freedom outside that of the other, and his freedom is therefore illusory. But this also subverts his aim of acting against his own self-interest, as this too cannot be entirely separated from the other. In the scene with the prostitute, the line between masochism and sadism is crossed; his ultimate aim may be to hurt himself, but because he needs the other to affirm him, he can only do that by hurting Liza.

The question that remains is: how much does the underground man understand what is going on here? He makes a great deal of the fact that he is acutely self-conscious, that he sees, understands and feels everything about himself and his actions. Thus, like Chernyshevsky’s rational egoists, he comprehends the entirety of his life. But unlike the Nihilists’ “new men,” for whom this leads automatically to action unencumbered by doubt or dualism, for the underground man the consequences of this consciousness are negative: “being overly conscious is a disease” (p. 5), because it leads to “inertia” (p. 7) – self-consciousness prevents one from acting, as one is filled with all the hesitations, doubts and anxieties that such knowledge brings (pp. 8-9). And certainly, his narrative in part 2 of the novel appears to be the product of that self-awareness, as he looks unflinchingly at his past and understands what he has done to himself and to Liza. But can we really trust this? Are we expected to believe that this cynical, manipulative character is entirely straightforward in his narrative self-presentation? What is his text for? Is he seeking redemption? There are perhaps suggestions that this is the case, vague allusions to another ideal besides that of the Crystal Palace, and originally the novel contained a short passage that pointed to Christianity as that ideal. However, this was removed by the censorship, and has been lost, so beyond a few references in letters, we do not know precisely what it contained. In any case Dostoevsky, although annoyed that it had been cut, wrote the remainder of the novel in the knowledge that this passage had been removed (Bird, p. 83), so one should not overplay the significance of this possibility; we can, in the end, only interpret the text we have. And I would suggest that another factor is potentially more important in assessing the narrator’s motives: the form of the text as a type of confession. Distanced from the religious context, first-person confessional narratives that detail the writer’s or speaker’s crimes or misdemeanours inevitably raise questions about the reliability and honesty of the narrator. Ever since Rousseau’s Confessions (1769) – a work Dostoevsky knew well – the genre has been associated with parading one’s own faults for dubious reasons (see Coetzee for more on confessions in Dostoevsky and Rousseau). So the form can be seen as part of his continuing self-humiliation, but if it is this, can it also be an honest self-examination?

So Notes from Underground is a complex and multi-layered work, and I’ve barely scratched the surface today, but I hope I’ve given you some pointers to focus on, thinking in particular about how the narrator responds to the concept of rational egoism, and the interaction of his personality and his ideas. We will examine further aspects of those in next week’s seminar.

Sources

Bakhtin, Mikhail, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, trans. Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1984)

Berman, Marshall, All that is solid melts into air: the experience of modernity (Verso, 1982)

Bird, Robert, Dostoevsky (Reaktion Books, 2012)

Coetzee, J. M., “Confession and Double Thoughts: Tolstoy, Rousseau, Dostoevsky,” Comparative Literature, 37.3 (1985), 193-232

Dostoevskii, F. M., Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v tridtsati tomakh (Moscow-Leningrad: Nauka, 1972-90) | Dostoevsky’s texts in Russian | Dostoevsky in English

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, The House of the Dead, trans. David McDuff (London: Penguin, 2003) | Russian text | English translation

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, Notes from Underground, trans. Michael Katz (New York: Norton, 2001) (2nd edn) | Russian text | English translation

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, trans. David Patterson (Northwestern University Press, 1988) | Russian text

Frank, Joseph, Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time (Princeton University Press, 2010)

Hudspith, Sarah, Dostoevsky and the Idea of Russianness (London and New York: Routledge, 2004)

Jones, Malcolm, Dostoevsky and the Dynamics of Religious Experience (London: Anthem, 2005)

Rozanov, Vasily, Dostoevsky and the Legend of the Grand Inquisitor, trans. Spencer E. Roberts (Cornell University Press, 1972)

Walicki, Andrzej, A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism (Stanford University Press, 1980)

1 Comment