When I wrote a post on Herzen in London, my focus was primarily on the man himself, rather than his publishing activities. But much of the discussion generated by the post recently has focused on the Free Russian Press (Вольная русская типография), leading me to conduct some further research, supported significantly by the contributions of three readers: Richard Ekins, Sean Mitchell and Hilary Chapman (their comments can be read in the discussion thread here). As the comments show, the emphasis has been on building a case for the Marchmont Association in Bloomsbury to approve a plaque commemorating the Free Russian Press. Herzen has fallen somewhat out of scholarly fashion of late, but the Press played a hugely important role in Russian political and intellectual life both at home and in emigration, so it is certainly worth celebrating, particularly in this year of his bicentenary. In this post, to mark the anniversary itself (Herzen was born in Moscow on 6 April 1812), I want to bring together all the evidence into a (hopefully) more readable narrative, and untangle the confusion that for some reason has previously surrounded the Press, and has led to some rather muddled versions of events appearing in various studies of Herzen over the years.

Alexander Herzen established the Free Russian Press in the spring or early summer of 1853, less than a year after his arrival in London. In an open letter of 20 May 1853 to the editors of Democratic Poland [Польский демократ], alongside whose press the Free Russian Press would initially be housed, Herzen stated: ‘Основание русской типографии в Лондоне является делом наиболее практически революционным, какое русский может сегодня предпринять в ожидании исполнения иных, лучших дел.’ [The founding of a Russian press in London is the most practical revolutionary action a Russian can undertake today in anticipation of fulfilling of other, better actions.] Aleksandr Gertsen, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v tridtsati tomakh (Moscow: Nauka, 1954-65), XII, p. 79. (Further references to this edition will be given as volume and page numbers in parentheses, with links to the on-line edition which can, however, be somewhat temperamental.)

While Herzen’s initial announcement, ‘ВОЛЬНОЕ РУССКОЕ КНИГОПЕЧАТАНИЕ В ЛОНДОНЕ: БРАТЬЯМ НА РУСИ’ [A Free Russian Press in London: to our Brothers in Russia], stated that the Press would open on 1 May 1853 (‘С первого мая 1853 типография будет открыта’, XII, p. 64), other evidence points to a slightly later date. In the article ‘РУССКАЯ ТИПОГРАФИЯ В ЛОНДОНЕ’ [The Russian Press in London] Herzen dates it to 1 June 1853 (XII, p. 237): : ‘С 1 июня 1853 наш печатный станок не прекращал работу, несмотря на все осложнения’ [Since 1 June 1853 our printing press hasn’t ceased working, despite all the difficulties]. However, the amazingly useful Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva A. I. Gertsena, 1851-1858 [A Chronicle of the Life and Works of Alexander Herzen, 1851-1858], ed. B. F. Egorov et al (Moscow: Nauka, 1976), p. 150, dates the start of the press even later, to 22 June 1853, citing as evidence a letter to Maria Reichel, dated 25 (13) June 1853 (XXV, p. 77), in which Herzen he writes ‘Типография взошла в действие в ту же середу [sic]’ [The press went into action this Wednesday]. But the waters are muddied further by a comment a few pages earlier in another letter to Maria Reichel (XXV, p. 69), dated 30 May 1853, on the publication in the Polish journal of his article «Юрьев день! Юрьев день!» [St George’s Day!]: ‘Типография шумит и идет вперед’ [The press is making a racket and moving forward]. It’s hard to see why Herzen would make such a comment about the supposedly already-established Polish press, but if the Russian press was already working by this point, why would this important article – a call for the emancipation of the serfs – have appeared in the Polish journal? Combined with the later letter, it suggests a brief period during which the setting up of the Press was in progress, but perhaps nothing had yet actually been published.

If there remains some doubt about the precise starting date of the Press, it is possible to establish its exact location: 38 Regent Square. The title pages of one of Herzen’s major publications from 1853, Du Developpement de Idees Revolutionnaires en Russie, provide evidence of both the date and address (and indeed, the original publications – or, in most cases, the facsimile versions published by the Soviet Academy of Sciences, for surprisingly few of these editions have made it onto either Google books or archive.org – have proved the most reliable source of information for much of this research).

Regent Square, situated between Tavistock Place and Sidmouth Street, still has some original buildings, but sadly it seems that no. 38 was on the northern side of the square, which has been redeveloped, where the Eastern block of Rodmell House now stands.

And although it would be lovely to discover this was the same address that housed subsequent generations of revolutionary exiles, my suspicion is that there was no such continuity. Nevertheless, Regent Square and the streets next to it certainly provided a home to Eastern European revolutionaries for many years; my post on Lenin in London records some of the residents in the vicinity.

The arrangement with the Polish Democratic Society lasted almost eighteen months, until December 1854. In Byloe i dumy [My Past and Thoughts], Herzen describes the meeting with Stanislaw Worcell in November 1854 which decided on the split of the two presses (XI, pp. 141-3). He told Worcell, ‘я напишу письмо, в котором скажу, что хозяйственные распоряжения заставляют меня перевести типографию, но что это не только не значит, что мы расходимся, но, напротив — что у нас вместо одной будут две типографии. Письмо это вы можете напечатать, если желаете, или показать кому угодно.’ [I will write a letter in which I say that economic arrangements force me to move the press, but this does not mean that we are splitting up – on the contrary, instead of one press there will be two. You can publish this letter if you want to, or show it to whomever you want]. The ‘economic arrangements’ were the debts of Leon Zienkowicz, in whose name the lease on 38 Regent Square was signed, which meant the bailiffs were expected (p. 142).

At this point the Free Russian Press moved into its first independent premises at 82 Judd Street, Bloomsbury. The announcement ‘РУССКАЯ ТИПОГРАФИЯ В ЛОНДОНЕ’ (XII, pp. 237-8) states: ‘Можно непосредственно обращаться в русскую типографию, 82, Judd street, Brunswick Square, Londres, à M. L. Czerniecki’ [The Russian Press can be addressed immediately at 82 Judd Street…]. This is the final entry in the volume of the Complete Works listed under 1854, and the editors’ commentary (XII, pp. 531-2) gives several indicators in the text to confirm this date. Moreover, a letter from Herzen to Worcell of 22 (10) December 1854 (XXV, p. 221) states: ‘вы уже знаете от гражданина Жабицкого, что перемещение Русской типографии было вызвано чисто экономическими соображениями. Позвольте же мне еще раз повторить вам это. Ничто не изменилось в наших отношениях — только у нас теперь две типографии вместо одной.’ [You already know from citizen Zabicki that the relocation of the Russian press arose out of purely economic considerations. Allow me to repeat that to you once more. Nothing has changed in our relations – only we now have two presses instead of one.] The use of the past perfective here implies the move has already happened, and Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva A. I. Gertsena agrees, dating the separation of the Free Russian Press from the Polish Democratic Society and move to 82 Judd Street to around 20 December 1854 (p. 216).

Happily, 82 Judd Street is one of the few original buildings from that period to survive on the street, and has been located by Richard Ekins as the present-day 61 Judd Street, now home to Bloomsbury Design.

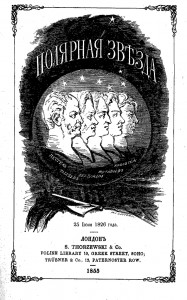

It was at this address that the work of the Free Russian Press really took off. In 1855, Herzen published the first volume of Poliarnaia zvezda [Polar Star].

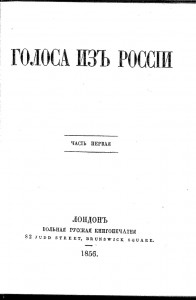

Much of the first volume was written by Herzen himself, although there were also letters by Michelet, Proudhon, Mazzini, and Hugo, and the correspondence between Belinsky and Gogol. In the following year, in addition to the second volume of Polianaia zvezda, the first volume of the collection Golosa iz Rossii [Voices from Russia], which featured articles by Konstantin Kavelin and Boris Chicherin, was also published at the same address:

In April 1856 Nikolai Ogarev arrived in London and joined Herzen in working on the Press. Perhaps this, and the success Poliarnaia zvezda in particular was enjoying precipitated the next move. On 11 December (29 Nov) 1856, the Press was still located at 82 Judd Street; in a letter to Malwida von Meysenbug on that date (vol XXVI, p. 53), Herzen wrote, ‘вы можете по-прежнему писать Чернецкому: 82 Judd Street, Brunswick Sq<uare> (т. е. на типографию), так как я не знаю его домашнего адреса.’ [You can always write to Czerniecki at 82 Judd Street … (that is, to the press), as I don’t know his home address].

But less than a week later, the Press had already moved. Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva A. I. Gertsena (p. 315) states that the second edition of the pamphlet Kreshchenaia sobstvennost’ [Baptised Property] was published (with a new introduction) in 1857 with a new address: 2 Judd Street. ‘На этой брошюре впервые обозначен новый адрес В.Р.Т.: 2 Judd Street, Brunswick Square. Помещалась здесь до 1 Марта 1860.’ [This pamphlet contains the first reference to the new address of the F.R.P: 2 Judd Street, Brunswick Square. The press was based here until March 1860]. The official publication date for this second edition is 1857 (see item no. 22 in this bibliography), but the new introduction is dated 25 October 1856 in the Complete Works (XII, pp. 94-6).

Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva A. I. Gertsena (p. 315) in fact dates the publication to ‘Around 16 December 1856,’ which seems to be confirmed by a letter to Maria Reichel of 16 (4) December 1856 (XXVI, p. 53): ‘Еще посылаю вам втор<ое> изд<ание> «Крещеной собственности» — там следует прочесть введение.’ [I am also sending you the second edition of ‘Kreshchenaia sobstvennost” – it’s worth reading the introduction.] This does strongly suggest that it was already in print.

As established by Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association, the building at 2 Judd Street – straight across the road from the first independent premises of the Press – has long since disappeared, replaced by the dog-walking area and toilet.

(Insert appropriate comment about the dustbin of history here.)

Other evidence supports the fact that 2 Judd Street was the second independent address of the Press, following 82 Judd Street (the reverse order has been given in more than one publication), for example a letter to Maria Reichel from 24 (12) October 1857 (XXVI, p. 133): ‘Говорите всем русским, чтоб адресовались в типографию к Чернецкому, — это гораздо вернее, и рукописи бы посылали так же. Адрес на всякой книжке найдут: 2 Judd Street, Brunswick Square.’ [Tell all the Russians to address things Czerniecki at the press – that’s more correct, and manuscripts could also be sent there. The address can be found on any [of our] books: 2 Judd Street, Brunswick Square.’]

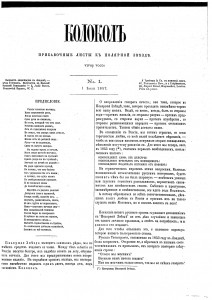

It was at 2 Judd Street that the Free Russian Press achieved its greatest success, as it was here that Kolokol [The Bell] was first produced. The publication was initially announced in the third volume of Poliarnaia zvezda (giving the 2 Judd Street address), dated 13 April 1857 (XII, pp. 357-8), and the first edition of Kolokol was published on 1 July 1857, the 2 Judd Street address appearing beneath the title.

Kolokol (as well as the other publications) continued to be produced at 2 Judd Street for more than two and a half years. The final issue of Kolokol to appear from that address was no. 63, dated 15 February 1860:

The next issue, dated 1 March 1860, is addressed 5 Thornhill Place, Caledonian Road:

As we’re now moving out of the immediate Bloomsbury area, this is essentially where my research ends for the time being, so just to sketch in the rest of the history of the Free Russian Press in London: 5 Thornhill Place was incorporated into Caledonian Road whilst the Press was sited there. The change must have taken place around June 1862, as the 1 July 1862 edition of Kolokol has the address 136 & 138 Caledonian Road. (See Sean Mitchell’s and Hilary Chapman’s notes dated 24 and 27 February, and 4 April, in the original comments thread on this question.) This address does still exist, although I was surprised to find that the two houses were in separate blocks (138 on the left of the picture is part of the block that was obviously originally on Thornhill Place, but which has now been opened up to form a sort of square on Caledonian Road itself).

I wonder whether the Press initially occupied only one of these buildings (138?), and then expanded operations into the other – this seems to me the most likely solution, though I need to do a bit more digging to see if there is any evidence for this.

The Free Russian Press moved from Thornhill Place/Caledonian Road in July 1863, with Herzen’s address at Elmfield House, Teddington being given on subsequent issues of Kolokol. This was the period of the Press’s decline following its support for the Polish uprising in that year, as I described in my previous post; one assumes that by this stage larger premises were no longer either required or possible. Then, as Hilary Chapman states in the comments (9 March 2012), from July 1864 ‘until the final edition of Kolokol published in England [in 1865], the address of the press was given as Jessamine Cottage, New Hampton, Middlesex.’ I have also come across this final address elsewhere, but more research into the post-Judd Street addresses will have to wait for now, in particular the question of whether the Press was in fact also situated here during the Elmfield House period. (I’m not sure, however, that Hampton could be described as a ten-minute walk from the Herzen residence.)

Having collated the evidence here, I’ll return to other aspects in future posts, including Herzen’s place in Bloomsbury’s literary history, and my thoughts on undertaking and presenting collaborative on-line research. But I would like to reiterate my thanks to Richard Ekins, Sean Mitchell and Hilary Chapman for their contributions and for making this process so interesting and enjoyable.

Sources consulted

E. H. Carr, The Romantic Exiles: A Nineteenth-Century Portrait Gallery (London: Victor Gollancz, 1933)

B. F. Egorov et al, Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva A. I. Gertsena, 1851-1858 (Moscow: Nauka, 1976)

A. I. Gertsen, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v tridtsati tomakh (Moscow: Nauka, 1954-65)

Francoise Kunka, Alexander Herzen and the Free Russian Press in London, 1852-1866 (Saarbrucken: Lmbert Academic Publishing, 2011)

Martin A. Miller, The Russian Revolutionary Emigres, 1825-1870 (Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1986)

Monica Partridge, Alexander Herzen, 1812-1870 (Paris: Unesco, 1984)

Monica Partridge, ‘Alexander Herzen and the English Press’, Slavonic and East European Review, 36 (1958), 453-470

Kate Sealey Rahman, ‘Russian Revolutionaries in London, 1853-70: Alexander Herzen and the Free Russian Press’, in Foreign-Language Printing in London 1500-1900, ed. Barry Taylor (Boston Spa and London: The British :Library, 2002), pp. 227-40

Kathleen Parthé

/ April 7, 2012The Moscow Times (March 30, 2012) carried an op-ed piece on Herzen as Russia’s first blogger. A HERZEN READER, containing 100 first-time translations of Herzen article from Kolokol, will be published by Northwestern UP this fall.

Sarah Young

/ April 8, 2012I look forward to the Herzen reader – thanks for alerting me to this. I’m rather sceptical about the ‘first blogger’ claim, not only because he wasn’t the only person involved in this sort of publishing venture at the time (Dickens?), but mainly because the comparison itself seems dubious. Still, it’s good to know there is interest in Herzen out there – I think it is time for a reassessment.

Richard Ekins

/ April 11, 2012Sarah – a brilliant job – thank you so much. Acknowledgements can, of course, be tricky but I would like to reiterate my credit to Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association, for locating the 2 Judd Street site.

Sarah Young

/ April 12, 2012Indeed so! I’ve added a line to the post to acknowledge Ricci’s work.

Richard Ekins

/ April 12, 2012Excellent news! I’m glad to report that the Marchmont Association committee have just given the go-ahead to the Herzen/Free Russian Press plaque, subject to permissions and fund-raising.

Any contributions to the fund would be most appreciated – officially through Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association – but anyone is most welcome to email me with initial enquiries.

Richard Ekins

/ April 28, 2012To continue the spirit of collaborative work, I wondered if anyone had any thoughts on the best wording for the Marchmont Association blue plaque. Have a look at their site for precedents, but this will be the first time they have honoured a building, premises, or work place, etc.

For possible precedents, see: http://openplaques.org/plaques/8247

http://www.islington.gov.uk/islington/history-heritage/heritage_borough/bor_plaques/recent_plaques/Pages/sickertplaque.aspx

Richard Ekins

/ January 2, 2013The Marchmont Associaton has now decided on the wording and a mock-up of the plaque has been prepared. Just three more steps to go: (1) funding; (2) erection of the plaque; (3) unveiling ceremony.

Considerable funding has been promised already, but there is still some way to go. Any contributions to the fund would be most appreciated – officially through Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association – but anyone is most welcome to email me with initial enquiries.

See http://www.marchmontassociation.org.uk/news-article.asp?ID=124

Richard Ekins

/ April 5, 2013I am pleased to say that the Marchmont Association has raised the required funds to enable the Herzen plaque to proceed. Further details will follow.

Fairhaven

/ July 31, 2014Excellent site! Many thanks for making this data available.

1. I am trying to determine the relationship between Alexander Herzen’s Free Russian Press, and Felix Volkhovsky said to be editor of Free Russia in London in 1896-7. Any connections between these publications or individuals?

REF: Felix V. had been convicted in Russia for “liberal views” and spent 7 years in solitary confinement in St Petersburg’s Schusselberg fortress, eleven years in exile in Siberia, then escapted to Canada using the alias “F.Brant.” Volhovsky later joined the “Social Revolutionaries” (Schiffrin quotes Free Russia, pp 13, 15-6); For the entire reference to Volkhovsky, see Schiffrin, (135).

2. I also noted Wikipedia’s reference to Herzen’s financial relationships with Baron Rothschild. Any more on this? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Herzen: “His assets were frozen because of his emigration, however Baron Rothschild with whom his family had business relationship, negotiated the release of Herzen’s assets, which were nominally transferred to Rothschild.”

Victor Heard

/ July 23, 2015I am surprised that there is no mention of the period when the Free Russian Press was located at 11 Spring Gardens, SW1. I am not a Russian history scholar but was informed of this in the late eighties by someone who was. It has always amused me that the site was subsequently occupied by the British Council. I imagine that in the soviet era there was a committee deep in the bowels of the Kremlin whose task was to try to explain the significance of HMG’s decision to obliterate the site of the press of the man who had paved the way for the emancipation of serfs and created the atmosphere in which communism might grow, and replace it with the organ of Britain’s cultural policy abroad. The likelihood, of course, is that HMG just did not know who Hertzen was, let alone where he worked.

Sarah Young

/ July 31, 2015The reason there is no mention of it is that nothing in my research of or reading on the Free Russian Press, or that of my colleagues, has revealed anything relating to that location. I know Herzen lived at 4 Spring Gardens early during his stay in London – I mention that in another post, but it was a year before the foundation of the Press. If there is any evidence of the Press being located at this address I’d very much like to see it.

Sarah Young

/ July 31, 2015Apologies for the long delay in replying! There was no connection between Herzen and the later revolutionaries, except that the latter were very much aware of their heritage and Herzen’s role in it, and just as Herzen used the name ‘Polar Star’ to advertise his own work as part of the Decembrists’ lineage, so the later revolutionaries did the same with Herzen.

I’m afraid I don’t know anything more at the moment about the Rothschild connection (except to suggest that it was one of the things that later allowed the Tsarist government to propagate the idea of an international Jewish conspiracy).

Fairhaven

/ July 31, 2015Since Herzen in his own memoirs specifically mentions the Rothschild connection, deflecting that fact onto “the Tsarist government’s” view of their political enemies is not an objective treatment of Herzen’s own memoirs. These memoirs were not compiled by the “Tsarist Government” but Herzen himself, an opponent of that Tsarist government. Obviously this is a highly sensitive report, particularly for those that need to operate within the British academic establishment, but this is nevertheless a fact. It points directly to the financial support that kept Herzen operating and indirectly funded his protege Mikhail Bakunin, founder of the Anarchist Movement and key partner of Karl Marx in the First International (however temporary that may have been). An awareness of the financial support for these movements is fundamental to a complete understanding of them.

Sean Mitchell

/ February 3, 2017For the rest of Herzen’s London locations see:

YOUTUBE film: ALEXANDER HERZEN PART 1

This is an on-line guided tour to Herzen’s story in these locations with London Blue Badge Guide Sean Mitchell