Whilst doing some research for my Russians in London series (to be resumed at some unspecified point), I came across a truly unexpected document from the pages of Chums, a middle-class boys’ weekly magazine published between 1892 and 1941, later associated with the scout movement, but in its early years probably most notable for its serial publication of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island in 1894. The article in question, from November 1893, is an interview with Sergei Stepniak-Kravchinsky. The very fact of an interview with such a figurehead of the revolutionary movement (who, let us not forget, had assassinated the chief of the ‘Third Department’ – the secret police – General Mezentsov) in a Boy’s Own-type publication is curious enough, but the subject of the interview is perhaps even more extraordinary: Russian boys’ games.

I have to admit at first I couldn’t understand why Kravchinsky would want to be involved in something so trivial – it seems to go against everything one ever reads about Russian revolutionaries, who were nothing if not serious and single-minded. But then I started thinking about the motives of the interviewer (one Frank Banfield). For readers of Chums, Kravchinsky – pseudonym and all – would represent the height of daring. The comparison with pirate captains and highwaymen – equally regarded as friendly to young boys when off duty – indicates a view of Russian revolutionaries as exotic swashbucklers. But that in itself, it seems, is sufficiently exciting for young minds; delving any deeper would quickly lead into more problematic territory, hence the anodyne subject matter of Russian versions of hopscotch and skittles. And that, despite initial appearances to the contrary, would surely accord entirely with Kravchinsky’s motives, which I suspect were mainly to do with refining his public persona. The interview allows him to have it both ways; he remains the dashing revolutionary of boys’ imaginations, whilst showing how normal, unthreatening, and even cuddly he is. In exposing the dishonesty of the boys who cheat at Vibitki, he emphasizes his own honourable nature, so that when, at the end of the conversation, he refers to the oppression of young people in Russia, the righteousness of his cause is clear, the bland response of Mr Banfield notwithstanding.

So, for your delectation, I present possibly the strangest contribution to the literature of Nihilism ever written:

CHUMS, 8 Nov 1893, p. 169

RUSSIAN BOYS AND THEIR GAMES

A Chat with Stepniak, the Russian Nihilist

Is there any man in London who knows more about the ways of conspirators than another, that man is Sergius Stepniak. Guy Fawkes wasn’t in it with the plotters whom this gentleman is hand-in-glove with. The Czar won’t have him in Russia at any price. Still, I knew that persons who can plan revolutions are often – for that matter, like pirate captains and highwaymen – personally very amiable.

‘He’s just the man,’ thought I, ‘to tell one something interesting about Russian boys and their games, and that will suit ‘CHUMS’ admirably.

So, if men with masks and daggers had lurked at every corner of the road, I don’t think I should have been daunted in the least, after my mind was made up as to my duty.

Consequently, about four in the afternoon, I might have been seen knocking at the door of a neat villa-cottage in Blandford Road, Turnham Green. Away on the right from the front door-step one obtaind quite a pretty view of the Chiswick meadow and woodland. But there was no time for mooning over landscapes, though there was in the near background such a dear old square-towered church, ‘bosomed high in tufted trees.’ A sudden rumpus arose, a very loud fierce barking, and on the door being opened by a comely maid-servant, two black dogs rushed forward. I didn’t turn a hair, because I keep three dogs of my own – fox-terriers – Jack, Floss, and Tiney, if I may go into such details. These two black ones must have known I liked dogs, for they began wagging their tales; and after the servant showed me into the drawing room they were as quiet as mice, and I saw no more of them.

In a few minutes Mr. Stepniak came in, and we shook hands. He was smoking a briar; and his request, I took my own pipe out of my coat-pocket, and we puffed away in concert.

‘Is your real name “Stepniak”,’ said I, ‘or is it only your writing name?’

‘It’s my writing name,’ said he.

‘What is your real name?’ I asked.

He smiled, shrugged his shoulders, and, in a word, declined to tell me. Here was a delightful mystery – a man who had some good reason or another for refusing to say who he was.

Of course, I did not press him on the matter, because that would be impolite. Therefore, I said –

‘I approach you, Mr. Stepniak, on behalf of “CHUMS,” a paper with an enormous circulation among the boys of the British Empire.’

He immediately assumed an attitude of more respectful attention.

‘What games,’ said I, ‘do Russian boys play?’

‘They play ball,’ said he.

‘Nothing else?’ I asked.

‘When I was a boy myself,’ he said, ‘I never played.’

I looked at him with some severity of manner, as I observed –

‘But what do the boys do, then?’

‘They read,’ he said slowly. Then recollecting himself, he went on –

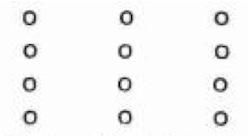

‘Oh, yes, I remember. We have a national game. The knuckles of sheep! If the joints of the feet of the sheep are taken, they will make something like that:-

‘In Russian we call that Babka; the plural is Babki.

‘We put the knuckles in rows, so:-

Each boy playing has his own knuckle, filled with lead, and each throws his own knuckles at the rows, and tries to overturn as many of them as he can.’

‘Have you any other first-class game?’ I asked anxiously.

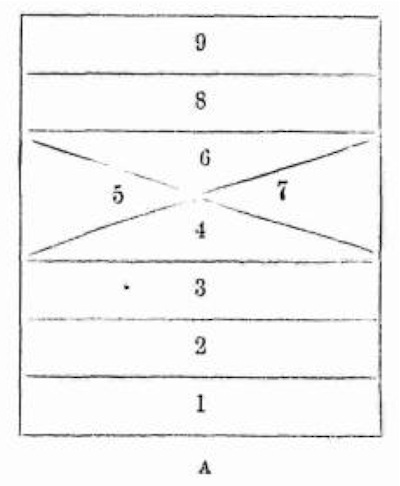

‘Yes, we have another called Gorodki, which means fortress or town, It is just like Babka, only it is played with pieces of wood, put in rows, like this:-

– three or four rows or more; then each boy throws at them a piece of wood shaped in this fashion’:-

‘What other fun have the Russian boys?’ I asked.

For answer, Mr. Stepniak drew this figure, which the boys, he said, marked out on the ground:-

Each boy playing,’ said Mr. Stepniak, ‘takes a little stone. One begins and throws it into No. 1 division. Then he hops up to it, and if he knocks it out with one twist of his foot, he can go again, this time throwing it into No. 2.

‘The stone must always be jerked out over the end marked A. It must never rest on a line. If it does, the player must pick it up, and another little Muscovite comrade go on.’

‘What do you call that?’ I asked.

‘I have forgotten the name,’ Mr. Stepniak replied sadly.

‘It reminds me, said I, ‘of “Hopscotch,” a game I played as a boy down in Cornwall.

‘But,’ I continued, ‘you must have some other games?’

‘Yes,’ said Mr. Stepniak, there is Svaika. It is played with sticks like this,’ and he drew roughly as follows:-

‘This is a pointed piece of wood. One boy fixes his piece in the ground, and another boy tries to hurl his own pointed cudgel in such a way as to knock the other’s out of the earth, and at the same time to fix his own in the ground.’

‘Anything more?’ I asked.

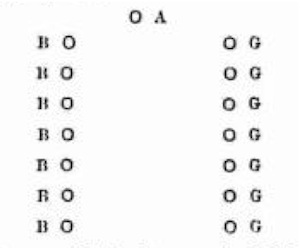

‘Well, there is Gorelki,’ said he. ‘Boys stand behind each other in a line. About a foot from each one is a girl, so:-

‘A is a boy, and the boy and girl farthest from him start off running, and try to meet ahead of the others before A catches them. If they escape, they take their place just in front of A. Then the next pair start. It A catches one, the boy has to take his place, while he plants himself with the girl at the head of the line.’

‘Do you play “Blindman’s Buff”?’ said I.

‘Of course,’ said Mr. Stepniak. ‘That is an international game. Ah, but I must tell you, at Easter, they play Vibitki. Each boy has an egg – a red egg. First they knock the small ends together till one is broken. The boy that breaks both ends of the other’s egg with his own gets that egg as his prize. It is,’ went on Mr. Stepniak, ‘quite a science in buying to recognize which egg has the thickest shell, testing it with tte teeth. And they cheat at it.’

‘The dishonest little wretches,’ I exclaimed. ‘How is it done?’

‘They prick a little hole in the side of the egg and suck out the white. After that they pour in a thin glue, which hardens at the ends when they are heated over a fire; and, of course,’ said Mr. Stepniak, ‘no ordinary egg has a chance in a contest with eggs prepared in this fashion.’

After that he explained to me Kator, a drawing-room game played with eggs.

‘Don’t your boys play cricket?’

‘No,’ said he.

‘Nor football?’

‘No,’ he again replied, ‘but many games with ball.’

From what Mr Stepniak here told me I inferred that Russian boys know a thing or two about ‘Rounders.’

‘Boys,’ said I, ‘in Russia are not oppressed, are they?’

‘Oh yes, they are. At first the Government of the Czar only put spies on students; now they put them on boys, so as to nip Nihilism in the bud, as they would say. Boys of fourteen are sent to Siberia. 300 young people under twenty are exiled there every year.’

‘What an awful shame,’ I said; and I assured him that ‘CHUMS’ readers would be heart and soul with me in this sentiment. Then I got up and wished Mr. Stepniak ‘good-bye.’

FRANK BANFIELD

Alison

/ October 16, 2011First, Sarah, hi–I’ve been reading your blog for a while, but have not yet followed through on the urge to click through to comment. This, though, is so very, very strange, that I finally have. The only thing that makes this seem not utterly unexpected is, of all things, having read Byatt’s The Children’s Book. The image of very late nineteenth century English life she portrays is one in which radicals and revolutionaries and anarchists DO actually appear in these sorts of unexpected, everyday ways. But even for that, this, with its focus on games, seems extreme!

Unless you’d prefer I not, I’m going to link over here from the Russian history blog I’m collaborating on–because this is, indeed, worthy of note, in its utter bizarreness.

Sarah Young

/ October 16, 2011Hi Alison! Indeed Nihilists do crop up quite frequently in 19th-century British literature and life, but I still found this the most bizarre example!

Do please link to it from the Russian History – I’m a regular reader of that too.