I’m no fan of Lenin, but he spent a good deal of time in London, so must be included in this series. I haven’t chosen this mugshot as an expression of my disapproval – it’s just that most of the photos that are available were taken after the revolution, and this one is the closest I could find in date to his first, and longest, visit to London. No doubt posing for portraits was not really a priority for an underground revolutionary.

But if pictures are scarce, source material on Lenin’s connections with London isn’t a problem, at least in terms of its availability. The difficulties lie elsewhere. Obviously no sort of history involves the unambiguous recitation of ‘the facts’, but works about Lenin bear greater resemblance to hagiography than history, and Krupskaya receives much the same treatment. When I read that ‘one is amazed by her rich memory, expressive style and accuracy … Grief and the pain of her loss sharpened Krupskaya’s memory, and those first years of revolutionary work and life together seemed as clear as yesterday’ (Muravyova, p. 21), I truly wondered whether I had read the same Reminiscences of Lenin as the authors of Lenin in London (and whatever the inadequacies and inaccuracies of the latter work, it is the main source on this topic, so all page references given are to this book, unless otherwise stated). The excesses of Bolshevik-speak occasionally provide amusement, as when they quote M. Essen on Lenin in Switzerland: ‘He climbs up a wonderful mountain, yet he isn’t thinking about the mountain at all, but about the Mensheviks’ (p. 106), but generally it’s just turgid. There’s also the need to read between the lines, particularly where Stalin and Trotsky are concerned, because of the re-writing of Soviet history. Despite these problems, I’ve used a number of Soviet sources, as a) many of them are available on the net, and many of these are contemporary(-ish), and b) Western sources, having other axes to grind, are generally less concerned with the details of location that interest me. Helen Rappaport’s recent book Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, tells a good story, but [comment withdrawn] has a rather relaxed approach to citing sources, which makes it extremely difficult to check some of the claims she makes.

Lenin and Krupskaya left Germany because of increased persecution by the police, and arrived in London in mid-April 1902 to transfer the publication of Iskra, the newspaper of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). They were met at Charing Cross station by a fellow exile, Nikolai Alekseev, and used his address (14 Frederick Street, off Gray’s Inn Road) for correspondence at first, before finding accommodation ‘two steps’ from there, according to a letter from Lenin to Plekhanov (p. 19), at 30 Holford Square, Pentonville. The house is no longer there, and the block of flats that was built in its place, planned in the early 1940s, was originally going to be called Lenin Court. By the time it was completed a decade later, enthusiasm for things Soviet had waned, to say the least, and it was called Bevin Court instead. You can read more about it in this BBC article.

The Ulyanovs spent just over a year in London, living in Holford Square under the name of Richter and upsetting the bourgeois landlady Mrs Emma Yeo with their bohemian behaviour, which apparently included hanging curtains on a Sunday (p. 23). It is worth noting that Lenin always stayed around the fairly salubrious environs of Bloomsbury and Pentonville. His excuse was proximity to the British Museum, but am I alone in suspecting that he wasn’t actually that keen on rubbing shoulders with the proletariat, at least not on a regular basis?

At first there were practical difficulties, not least with language. Lenin and Krupskaya had translated Beatrice and Sidney Webb’s Industrial Democracy whilst in Siberia, but neither had any real experience of spoken English. The Takhtarevs – Konstantin, the former editor of Rabochaia mysl’, and his wife Apollinaria Iakubova from the St Petersburg group, living nearby at 20 Regent Square (only nos. 1-18 of the original houses are still standing) – took Lenin and Krupskaya under their wings and helped them in this respect, despite ideological differences. In May 1902 Lenin advertised in the Atheneum journal and was soon exchanging lessons with a Mr Raymond (or Rayment, according to Rappaport, p. 77), who worked for the publisher George Bell & Sons, a clerk, Mr Williams, and a worker named Mr Young (no relation) (p. 35). Predictably, Lenin in London informs us that the speed with which our hero mastered spoken English was nothing short of miraculous.

Lenin spent the mornings working at the Reading Room at the British Museum (and was highly impressed with ‘the world’s richest library’, as Krupskaya called it, but not by the museum). His ticket number was A72453. He then conducted Iskra business on the way home (continuing the tradition of Russian radical publishing in London).

The offices of Iskra were at 37a Clerkenwell Green (now the Marx Memorial Library) – Harry Quelch, the editor of the British Social Democrat weekly, Justice, made their printing press available, with Iskra just having to provide its own typesetters (p. 40). Numerous addresses where Iskra workers and other activists and sympathizers lived were used for correspondence. These included: the flat of L. Deutsch, narodnik, Social Democrat and member of the Emancipation of Labour group, at 26 Granville Square, off King’s Cross Road (p. 48); 22 Ampton Street, off Gray’s Inn Road, the new address of Nikolai Alekseev from October 1902; the flats of British Social Democrats A. Hazell, at 85 Avenell Road, Highbury, V. C. Clews, at 62 Mildmay Grove (near Newington Green), and W. Woodroffe, at some distance from the others at 26 Barset Road, Nunhead (not ‘Barsett Road, Nanhead’, as Lenin in London has it, pp. 76-80).

In addition, the Iskra editorial board rented a 5-room flat in Sidmouth Street, again just off Gray’s Inn Road, and this became a commune. Most of the sources I have read do not record the house number (Rappoport gives it as no. 14, p. 74), and in any case only three of the original houses survive. Julius Martov and Vera Zasulich (the latter had previous lived in London between 1894 and 1897 and, like Lenin, had made great use of the British Library; Bergman, p. 106) lived there in absolute squalor, by all accounts, and it was frequented by many visiting Russians, such as Plekhanov in September 1902 (p. 85) and, in the same month, a group of Social Democrats who had escaped from Lukyanovo prison in Kiev, including Maxim Litvinov (p. 91), future Soviet ambassador to the United States. Trotsky also visited when he arrived in October 1902; Lenin in London omits to mention this visit, but, perhaps surprisingly, given that it was written in 1933, Krupskaya does. Lenin also gave a number of speeches, including one on ‘the programmes and tactics of the Socialist-Revolutionaries’ at Liberty Hall, Whitechapel, on 29 November 1902 (p. 184), and on 21 March 1903 he spoke at a meeting to commemorate the anniversary of the Paris Commune at the New Alexandra Hall, Jubilee Street, Mile End. Louise Michel was another of the speakers (p. 185).

But all work and no play makes Volodya a dull revolutionary, and we learn that in between his extraordinary feats of intellectual labour and tireless activities for the revolutionary cause, Lenin enjoyed exploring London. He particularly liked walking in Primrose Hill and visiting Regent’s Park zoo (pp. 102-4), but many of his leisure activities do seem to have been connected with his work: he regularly attended Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park to listen to speeches, and visited socialist churches, including Seven Sisters’ Church on Seven Sisters’ Road (pp. 94-7). As Krupskaya tells us:

Ilyich studied living London. He liked taking long rides through the town on top of the bus. He liked the busy traffic of that vast commercial city, the quiet squares with their elegant houses wreathed in greenery, where only smart broughams drew up. There were other places too – mean little streets tenanted by London’s work people, with clothes lines stretched across the road and anaemic children playing on the doorsteps. To these places we used to go on foot. Observing these startling contrasts between wealth and poverty, Ilyich would mutter in English through clenched teeth: “Two nations!”

In May 1903, following a decision by the Iskra board to move to Geneva, which Lenin alone opposed, the Ulyanovs left London. But they returned soon afterwards, when the 2nd congress of the RSDLP was forced to move from Brussels because of police persecution, and reconvened in London, under the guise of an Anglers’ club, according to Alan Woods. The first session was held on 11 August 1903 (29 July o.s.) at the Communist Club at 107 Charlotte Street. The building that now stands there houses UCL student residences. For more on the history of the club, see Keith Scholey’s pamphlet. There don’t appear to be any records on where subsequent sessions were held.

The usual suspects were present: Trotsky, Plekhanov, Zasulich, Martov, Axelrod… According to tradition this was the congress at which the Russian Social Democrats split into the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, but in fact it was not at this stage a definitive rift. Few of the Soviet sources in any case give much detail on the substance of the differences. Most seem more interested in who was in which faction and what those factions were called than in the ideological differences between them – the description in the Short Course History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) is pretty typical in this respect. I suppose the idea is that the correct line (i.e. Lenin’s line) is beyond question and therefore doesn’t even need stating. If you are interested in some of the nitty-gritty, Lenin’s speeches are probably the best source, and Alan Woods gives an account that is very sympathetic to Lenin, but reasonably straightforward. After the congress, probably on 24 August 1903, Lenin led a group of Bolsheviks to Highgate Cemetery to visit the grave of Karl Marx (p. 141).

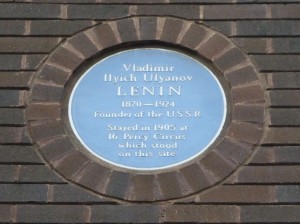

Two years later, in the wake of the 1905 revolution, the third RSDLP congress – the first Bolshevik congress – was held in London, from 12 April to 10 May 1905. There were between 40 and 50 delegates representing the various Bolshevik committees and the central committee (p. 150), including Lunacharsky and Bogdanov (Woods). Lenin, who chaired the congress, and Krupskaya, stayed around the corner from their old Holford Square Flat, at 16 Percy Circus, now marked with a blue plaque. There were also delegates staying at 9 and 23 Percy Circus (p. 149). I have not come across any details about where the sessions of the congress were held.

Two years later, in the wake of the 1905 revolution, the third RSDLP congress – the first Bolshevik congress – was held in London, from 12 April to 10 May 1905. There were between 40 and 50 delegates representing the various Bolshevik committees and the central committee (p. 150), including Lunacharsky and Bogdanov (Woods). Lenin, who chaired the congress, and Krupskaya, stayed around the corner from their old Holford Square Flat, at 16 Percy Circus, now marked with a blue plaque. There were also delegates staying at 9 and 23 Percy Circus (p. 149). I have not come across any details about where the sessions of the congress were held.

Lenin in London does have details of some of the extra-curricular activities: visits to the National Gallery and the theatre, the zoo and the Natural History Museum, the British Library and Highgate Cemetery, and also to a pub on Gray’s Inn Road, the Pindar of Wakefield (the book has ‘Pindor of Walkfield’, p. 149 – here and elsewhere, the translator obviously didn’t do much in the way of checking the spelling of English place names), which Lenin apparently frequented when he lived in the area. It’s now called The Water Rats, and is a well known music venue, notable, among other things, for hosting Bob Dylan’s first British gig in 1962. Another pub Lenin was known to visit with his comrades, and possibly one of the venues used for the congress, was the Crown and Woolpack, St John’s Street, Clerkenwell, now The Chapel hairdressing salon.

A third social venue, the Crown Tavern on Clerkenwell Green, proudly flaunts its reputation as the pub in which Lenin met Stalin for the first time at the 1905 congress, and the story is repeated in the BBC report on Lenin’s London haunts. Alas, this is a myth. Lenin may well have drunk in the pub during that congress or at other times, and possibly had a pint with Stalin at a later date (although the evidence doesn’t support this either), but Stalin most definitely wasn’t at the 1905 congress. Even the sycophantic Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute biography of Stalin, which tries its best to affiliate Stalin to Lenin’s victories and decisions from the earliest possible stage, doesn’t manage to place him at the scene, and states that the two men first met at the Bolshevik congress in Finland in December 1905-January 1906.

Stalin was, however, in London for the 5th RSDLP congress in 1907, but where he stayed is a source of some confusion. According to most sources, he lodged at Tower House, Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel (then a notorious doss house, now an improbably smart refurbished block advertising loft-style apartments to let). This article by Robert Service from the Evening Standard claims Stalin stayed at ’77 Jubilee Road’. There is no such place in the East End and I assume he means Jubilee Street. Rappaport says that after surviving couple of nights in Fieldgate Street (she calls the building Rowton House), Stalin moved to the greater comforts of ‘Jubilee Road’ (p. 156).

The 1907 congress was a much bigger affair than the Bolshevik event of 1905, with over 300 delegates. I’ve seen different breakdowns. Lenin in London says there were 103 Bolsheviks, 97 Mensheviks, and others from the Social Democratic parties of Poland, Latvia and Lithuania, and the Bund (pp. 165-6). Stalin claims there were 92 Bolsheviks and 85 Mensheviks. Woods has 89 Bolsheviks and 88 Mensheviks. According to Woods, the Menshevik delegates included Plekhanov, Martov, Axelrod, Deutsch and Dan, and the Bolsheviks Lenin, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Nogin, Bogdanov, Tomsky and others. Trotsky was present as a non-factional delegate, and others present included Maxim Gorky and Rosa Luxemburg. Felix Dzerzhinsky was due to attend but was arrested en route. Stalin, apparently, ‘had no voice in the proceedings as he had no credentials from any recognised party organisation in the Caucasus’ (Woods, part 3). Unsurprisingly, the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute biography paints a somewhat different picture, saying that Stalin took an ‘active part’.

The main congress was held from 13 May to 1 June (30 April-19 May o.s.) at the Brotherhood Church, on the corner of Southgate Road and Balmes Road, on the Islington/Hackney border. It’s now been replaced by an unprepossessing block of flats. But there was also a Bolshevik congress held at a socialist club in Fulbourne Street, off Whitechapel Road on 10 May (p. 167), A BBC4 programme, Watching the Russians, followed the trail of Russian revolutionaries in London, and William Fishman states that the door on the far left of the picture below led to this club. On 3-7 June, the second congress of the Latvian Social Democrats was held at King’s Hall, Commercial Road, Whitechapel (p. 172).

I have not come across any reference to where Lenin lodged during this visit, but Gorky, with whom he spent a good deal of time (they had only met once previously, but consolidated their friendship during the congress), stayed at the Imperial Hotel, Russell Square, and Lenin worried that the damp there would affect his health (pp. 176-7). In their spare time Lenin and Gorky visited the British Museum, and ‘the delegates warmly remembered … a discussion with Lenin on the grass in Hyde Park’ (p. 179) – a slightly unexpected picture. There are also reports that Lenin was seen drinking tea at the workers’ club at 165 Jubilee Street, Whitechapel, established by Rudolf Rocker’s Jewish anarchist group and the newspaper Arbeter Fraint (Fishman, p. 264). As he was in the area for the satellite conferences, this seems not unlikely – the club was not exclusively used by anarchists – but I’m less sure about the story that he created a scene by accusing another person at the club of being a Russian police spy and was arrested in the subsequent disturbance (Graur, p. 99). I haven’t found any other reference to Lenin being arrested in London. Other connections are made with the Jubilee Street Club by Rappaport. She says the inaugural meeting of the RSDLP congress was held there on 10 May (p. 156). This is not supported by other sources. The Whitechapel meeting was of the Bolshevik faction only, and the Fulbourne Street location seems much more likely. Her claim that Kropotkin was also there (introducing ‘his friend’ Lenin to a detective outside the club, p. 157), and indeed present at some of the main sessions of the congress, suggests a misunderstanding of the nature of the revolutionary movement. Nothing else I have read puts Kropotkin anywhere near the scene, and it seems highly improbable that he would have had any involvement with either the congress or Lenin.

In May 1908, Lenin returned to London to work in the British Library. He lodged at 21 Tavistock Place, near his old haunts of Sidmouth Street and Regent Square, and spent his time preparing materials for writing Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, which was published the following year. Lenin’s final, brief, trip to London was in Autumn 1911. He stayed at 6 Oakley Square, near Mornington Crescent (p. 188), and gave a lecture on ‘Stolypin and the Revolution’ at the New King’s Hall, Commercial Road, on 11 November (p. 193).

In May 1908, Lenin returned to London to work in the British Library. He lodged at 21 Tavistock Place, near his old haunts of Sidmouth Street and Regent Square, and spent his time preparing materials for writing Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, which was published the following year. Lenin’s final, brief, trip to London was in Autumn 1911. He stayed at 6 Oakley Square, near Mornington Crescent (p. 188), and gave a lecture on ‘Stolypin and the Revolution’ at the New King’s Hall, Commercial Road, on 11 November (p. 193).

Sources

Jay Bergman, Vera Zasulich: A Biography (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1983)

Central Committee of the C.P.S.U.(B.), ed., History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks). Short Course (International Publishers, 1939)

William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals, 1875-1914 (London: Duckworth, 1975)

Mina Graur, An Anarchist ‘Rabbi’: The Life and Teachings of Rudolf Rocker (New York: St Martin’s Press; Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 1997)

N. K. Krupskaya, Reminiscences of Lenin, trans. Bernard Isaacs (International Publishers, 1970)

Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, Stalin (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1947)

L. Muravyova and L. Sivolap-Kaftanova, Lenin in London: Memorial Places, trans. Jane Sayer (Moscow: Progress, 1983)

Helen Rappaport, Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (New York: Perseus, 2010)

Keith Scholey, The Communist Club (London: Past Tense, 2006)

Alan Woods, Bolshevism: The Road to Revolution (London: Well Red Books,1999)

Helen Rappaport

/ February 24, 2011Entry on Kropotkin from The Great Soviet Encyclopedia 1979.

‘He supported the Revolution of 1905–07 and spoke out against the punitive policy of the tsarist regime. As one of a small number of Russian émigrés, he was a guest at the Fifth (London) Congress of the RSDLP in 1907.’

Helen Rappaport

/ March 8, 2011I have now had time to go through my notes for Conspirator that are in storage and would like to respond further as follows:

One of the delegates at the 1907 Congress was Klimenty (later Marshall) Voroshilov. In his ‘Rasskazy o zhizni’ (Moscow: Nauka 1968 pp. 352 and 353) he clearly states that Kropotkin was invited to the 1907 congress as a special guest – not only that but he was so impressed with the Bolsheviks that he invited some of them back home to tea! In the end ten of the delegates visited Kropotkin at his home where his daughter Sasha served them tea from the samovar. A lively conversation ensued. Further – with regard to Highgate, I was slightly out of sync but not actually wrong. If you care to look at George Woodwock and Ivan Avakumovic ‘Peter Kropotkin, From Prince to Rebel’, Black Rose Books 1990, p. 262, you will see that it states: ‘In the autumn of 1907 [Kropotkin] moved from Bromley to Highgate, where he took a small villa in Muswell Hill Road.’ I would appreciate it if you would remove the entirely unjustified statement that my book ‘has numerous accuracies’. Thank you

Ian Morrison

/ March 26, 2014Does it really matter whether you are a “fan” of Lenin or not?

Carole Heath

/ May 11, 2015INTERESTING site the section about Lenin drinking at the Water rats theatre bar is of great interest to me as i had my wedding reception in the hall upstairs in 1970. I was not aware that it was no longer a pub.

Aman

/ May 26, 2016Dear Sarah

Is there anything to suggest one way or the other whether Lenin actually stayed for some time at the Frederick Street house upon arrival in London? I appreciate it was the correspondence address, but I don’t know whether Lenin was likely to hide his address, or if people staying in hotels didn’t give that as a correspondence address, or if there’s any such peculiarity which would offer a clue that I am missing.

Sarah Young

/ July 3, 2016I’ve not seen anything to confirm that one way or another. I do know that using correspondence addresses was standard practice because a significant amount of revolutionaries’ communications were sent through the regular postal system (this always surprises me) and they wouldn’t be too keen on advertising their real addresses to the authorities. That would suggest a correspondence address would be the last place Lenin would wish to stay, but on the other hand I’m sure the Okhrana generally knew where he was anyway, even with this bit of subterfuge.

Richard Mullin

/ February 16, 2017One venue I think you have missed is the Three Johns, just up from Angel tube station on White Lion Street.

This is mentioned in Leninskii Sbornik VI (p102) in connection with the Second Congress of the RSDLP in 1903. It seems that the 29-30 sessions took place there. The address is in Lenin’s notebook.

Best regards…

Sarah Young

/ March 5, 2017Thanks for this – will add it to the list.

Martin Allen

/ October 11, 2017On ‘Making history’ on Radio 4 on 1st Augst 2017 it was suggested that the Bolshevik party was formed at the current site of Saatchi & Saatchi’s headquarters in Charlotte Street. Saatchi & Saatchi’s current headquarters is 80, Charlotte Street.

Sarah Young

/ October 11, 2017I thought that’s where it was and an earlier version of this post suggested that, but I corrected it recently as someone pointed out the error.

Malcolm Archibald

/ August 4, 2018In “Listki ‘Khleb i Volya'” (London) No. 15, May 24, 1907, Kropotkin published a statement that reads in part: “I have never participated, nor will I ever participate, in any Russian social-democratic, or any other kind of social-democratic, congress.” This was in response to reports in the press that he had attended the 5th RSDLP congress. But the Russian historian V. V. Krivenky has discovered evidence that Kropotkin requested that his wife Sophia and her friend Fanny Stepnyak-Kravchinsky be allowed to attend one of the sessions.

Alan

/ August 14, 2018I think Helen Rappaport could well be right. The detective who mentions Lenin and Kropotkin was Edwin T Woodhall of the Political Branch (or ‘Special’) at Scotland Yard between 1910 and 1914. There is a press clipping here:

https://twitter.com/toplis_percy/status/1028611270273118208

Woodhall’s alleged encounter (whether first-hand or borrowed from elsewhere) may be a reference to Lenin’s lecture at New King’s Hall in November 1911. Both New Kings Hall & Jubilee Street maintained the ‘refugee centres’ described in his press story. Nellie Dick (aka. Naomi Ploschansky) was central to these relief efforts and appears to have been an associate of both Prince and Madame Kropotkin. Naturally both locations became the go-to place for lectures. Nellie/Naomi was in regular contact with the relief agencies in the area and it’s interesting to note that a co-boarder at the Percy Circus house where Lenin lodged in 1911 was Board of Guardians worker, Winifred Gottschalk, who is down on the census as ‘Suffragette – particulars unavailable’. According to interviews she gave in the last years of her life, Nellie/Naomi’s relief efforts were supported in the main from members of the East End Suffragette movement. Nellie/Naomi set up the Ferrer Sunday School at New Kings Hall, with no shortage of encouragement from the Kropotkins. So there does seem a plausible context for the claims.

Woodhall mentions Kropotkin’s Highgate residence in the press clipping. Personally I still don’t think its related from first-hand experience but there may be an element of truth in it.

Alan

/ October 23, 2018Interesting that 16 Percy Circus was the home of Philip Whitwell Wilson – who would become Liberal and Radical MP for St Pancras South in 1906.