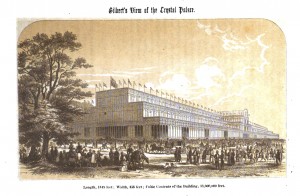

I’m going to skip one report, from Sovremennik, 29 (September 1851), Sovremennye zapiski pp. 63-4, which consists only of a rather dry description of works in gold, silver and precious stones (my plan is to publish the articles and translations separately, and this one will be included then). Instead I shall move straight to the final article, from the November-December issue, which covers the closing ceremony and awards. My initial reaction to it was that it wasn’t as interesting as the other reports, and certainly in its list of medals it doesn’t offer any special perspective. But then I realized that I’d actually come across very few descriptions of the closing ceremony (in contrast to the copious ink spilled on the opening), so it does have value from that point of view. The copy of the journal on Google books has the promised image of the Crystal Palace, so I’ve included that as well.

If you’re wondering about Mme Bocarm, mentioned in the final paragraph as one of the subjects of P. T. Barnum’s invitations, this refers to the case of Belgian count Hippolyte Visart de Bocarm and his wife Lydie, tried for poisoning her brother over a disputed will earlier in 1851 – the count was convicted and executed, but his wife was acquitted. The case was sensational enough to have made the pages of Sovremennik – in fact, in a couple of previous issues the story immediately followed the report from the Great Exhibition – which acts as a reminder that whatever we now tend to think of these journals and their reflection of Russian intellectual life, it was not all high-brow literature and penetrating philosophical debate.

ВЕСТИ ИЗ ЛОНДОНА: Всемирная выставка.

Современник, 30 (1851), Иностранние известия, 51-3.

Многие надеялись, что Лондонская выставка продлится еще несколько месяцев; но эти надежды не сбылись. В последних числах сентября, по распоряжению Исполнительной Коммиссии, в Кристальной Палате прибиты были объявления, что выставка закроется 11 сентября, и что после этого дня вход в Кристальную Палату открыть будет только для экспонентов. Тогда только все уже убедились в неосновательности слухов о продолжении выставки. Наконец наступило и 11 октября. В этот день вход в Кристальную Палату открыть был с девяти часов вместо двенадцати. Экспоненты суетились около своих произведений и спешили укладывать их. В четыре часа по полудни пятьдесят тысяч человек столпились вокруг хрустального фонтана и с нетерпением ожидали торжественного закрытия выставки. В пять часов раздалось торжественное пение народного гимна: “God save the Queen”, под звуки большого органа г. Дюхроке. Своды здания задрожали от нескольких тысяч голосов и как будто готовы были обрушиться. По окончании гимна, со всех сторон раздались аплодисманы и крики: ура! В двадцать минут шестого во всех галлереях зазвонили в колокола. Это значило, что пора уже расходиться по домам. Но публика все еще аплодировала и кричала: ура принцу Альберту, лорду Гранвилю, Пакстону, Королевской Коммиссии! и проч., и никто не думал уходить. Только в семь часов уже все разошлись, ито не без содействия полиции.

В понедельник и вторник, т.е. 13 и 14 октября, вход в Кристальную Палату открыть был только для экспонентов, которые должны были убирать свои произведения. В среду 15 октября все экспоненты в последний раз собирались в Кристальной Палате. В 12 часов прибыл принц Альберт. Виконт Каннинг, президент совета присяжных, прочитал отчет и решения присяжных о наградах медалями.

Из отчета, представленного президентом совета присяженых, видно, что число всех лиц, выставивших свои произведения в Кристальной Палате, простиралось до 17,000, и в том числе: из Англии и из всех английских колоний 9,734; из Франции и Алжира 1,736; из Германского Таможенного Союза и из различных государств Северной Германии 1,364; из Австрии 746; из Соединенных-Штатов 557; из Бельгии 512; из России 384; из Испании и Португалии 289; из Швейцарии 270; из Италии 148; из ганзейских городов 148; из Нидерландов 114; из при-балтийских стран 106; из Сардинии 92; остальное число из Индии, Северной Америки, Китая и проч. По определению совета присяжных роздано, в виде премии за лучшие произведения, 164 большие золотые медали; из них Англия получила 79; Франция 56; и всех прочие государства 37.

Большие медали распределены между различными государствами по классам, следующим образом:

1 класс. Руды и минералогические произведения: Франция 2: Великобритания 2, Пруссия 2; Австрия 1.

2 класс. Произведения химические и аптекарские: Франция 2: Великобритания 1: Тоскана 1.

3 класс. Произведения природы, употребляемые в пищу: Франция 4; Великобритания 1: Соединенные-Штаты 1.

4 класс. Произведения животных и растения: Франция 3: Великобритания 2.

5 класс. Машины: Великобритания 4; Франция 1; Бельгия 1.

6 класс. Механические инструменты и орудия лля мануфактур: Великобритания 15; Франция 4; Пруссия 2.

7 класс. Архитектура и проч.: Великобритания 3. (Эти три медали присуждены были: принцу Альберту, за выставленную им модель дома для рабочихъ; г.г. Фоксу и Гендерсону за постройку, и г. Пакстону за план Кристальной Палаты.)

8 класс. Судостроение, орудия и пр.: Великобритания 5; Франця 3; Австрия 1.

9 класс. Земледельческие орудия и инструменты : Великобритания 4: Соединенные-Штаты 1.

10 класс. 1 отд. Физические инструменты: Великобритания 16. Франция 9; Соединенные-Штаты 1: Пруссия 1: Швейцария 1: Тоскана 1: Голландия 1: Бавария 1.— 2 отд. Музыкальные инструменты: Великобритания 4; Франция 4; Бавария 1. — 3 отд. Часы: Франция: 2: Великобритания 1: Швейцария 1.

По 11, 12, 13, 14 и 15 классам не выдано ни одной большой медали.

16 класс. Шали: Франция 1.

17 класс. Книгопечатание, переплет и бумага: Императорская Венская Типография 1.

По 18 классу не выдано ни одной большой медали.

19 класс. Ковры, кружева, шитье и проч.: Великобритания 1: Франция 1.

По 20 классу не выдано медалей.

21 класс. Ножи и проч. Великобритания 1.

22 класс. Мелочные товары металлические и проч.: Великобритания 5: Франция 4; Пруссия 1; Бавария 1; Бельгия 1.

23 класс. Золотые, серебряные и брильянтовые вещи: Великобритания 6: Германский Таможенный Союз 3; Россия 1.

24 класс. Стеклянная посуда: Франция 1.

23 класс. Фарфор, фаянс и проч.: Великобритания 1; Франция 1.

26 класс. Мебель, обои и проч.: Франция 4: Австрия 1.

27 класс. Обработка минералов. Великобритания 2: Папская область 1: Россия 1.

28 класс. Выработанные произведения из растений и проч.: Велобритания [sic] 2; Соединенные-Штаты 1.

29 класс. Различные произведение: Франция 2.

30 класс. Изящные искусства, скульптура, модели и проч.: Великобритания 2; Франция 1; Пруссия 1.

Так окончился этот великолепный промышленный юбилей, на который собрались представители всех стран земного шара. Что теперь будет с Кристальной Палатой? останется ли она на прежнем месте, или разобрана будет на мелкие части? — об этом еще нет положительных сведений. (Во всяком случае здание Выставки так замечательно, что мы думаем сделать удовольствие нашим читателям, представив им фасад его, которого с часу-на-час ждем из Лондона.) Рассказывают, что один американец, некто г. Барнум, недавно приехал в Лондон с тем, чтобы купить у англичан великолепное здание Всемирной выставки и перевести его в Нью-Йорк. Г. Барнум, как видно, принадлежит к числу самых предприимчивых людей. Он обращался с своими предложениями ко всем театральными знаменитостям, бывшим в Лондоне, приглашая их в Америку. Говорят, он даже приглашал г-жу Бокарме дать несколько концертов въ главнейших городах Соединенных-Штатов и Мексики, хотя г-жа Бокарме нисколько не отличается артистическим талантом: она сделалась известною только по уголовному процессу, с которым уже знакомы наши читатели. Неизвестно, приняты ли эти предложения.

Image of the Crystal Palace from Sovremennik vol 30

News from London. The World Exhibition

The Contemporary, 30 (1851), Foreign News, 51-3

Many had hoped that the London exhibition would last several more months, but those hopes were not realized. In late September, on the instruction of the Executive Committee, an announcement that the exhibition would close on 11 September [sic] was fixed to the Crystal Palace, and that after that day, entrance to the Crystal Palace would be open only to exhibitors. Only then was everybody persuaded that the rumours about the continuation of the exhibition had no foundation. Finally 11 October arrived. On that day, the entrance to the Crystal Palace was opened from nine o’clock instead of twelve. The exhibitors were scurrying around their products and hastening to pack them. At four o’clock in the afternoon and fifty thousand people crowded around the Crystal Fountain, and awaited impatiently the exhibition’s closing ceremony. At five o’clock rang out the celebratory singing of the national anthem: ‘God save the Queen’, accompanied by the sound of Du Croquet’s large organ. The vaults of the building shook from several thousand voices, and it was as though it was ready to come crashing down. At the end of the anthem, from all sides rang out applause and cries of Hurrah! At twenty minutes past five bells began ringing in all the galleries. This meant that it was already time to go home. But the audience still cheered and shouted: Hurrah to Prince Albert, Lord Granville, Paxton, the Royal Commission! and so on., and no one thought of leaving. Only at seven o’clock had everybody departed, and then not without the assistance of the police.

On Monday and Tuesday, that is, 13 and 14 October, entrance to the Crystal Palace was only open to exhibitors who had to pack up their works. On Wednesday 15 October all the exhibitors gathered in the Crystal Palace for the last time. At 12 o’clock Prince Albert arrived. Viscount Canning, president of the jury, read the report and decisions of the jury on the award of medals.

From the report submitted by the president of the jury, it was apparent that the number of people who had exhibited their work in the Crystal Palace had reached 17,000, including: 9,734 from England and from all the British colonies; 1,736 from France and Algeria; 1,364 from the German Customs Union and from various states of Northern Germany; 746 from Austria; 557 from the United States; 512 from Belgium; 384 from Russia; 289 from Spain and Portugal; 270 from Switzerland; 148 from Italy; 148 from the Hanseatic cities; 114 from the Netherlands; 106 from the Baltic states; 92 from Sardinia; and the remainder from India, North America, China and so on. On the basis of the jury’s rulings, prizes were distributed for the best products, in the form of 164 large gold medals, of which Britain received 79, France 56, and all other states 37.

Large medals are distributed amongst the various states according to classes, as follows:

Class 1. Ore and mineralogical works: France 2: Great Britain 2; Prussia; 2 Austria 1.

Class 2. Chemical and pharmaceutical products: France 2: Great Britain 1: Tuscany 1.

Class 3. Products of nature, edible: France 4; Great Britain 1; The United States 1.

Class 4. Animal and plant products: France 3; Great Britain 2.

Class 5. Machines: Britain 4; France 1; Belgium 1.

Class 6. Machine tools and instruments for manufacturing: Great Britain 15; France 4; Prussia 2.

Class 7. Architecture and so on: Great Britain 3. (The three medals were awarded to: Prince Albert, for the model home for workers exhibited by him, Mssrs Fox and Henderson for the construction, and Mr. Pakston for the plan of the Crystal Palace.)

Class 8. Shipbuilding, tools, etc.: Great Britain 5; France 3; Austria 1.

Class 9. Agricultural implements and tools: Great Britain 4; The United States 1.

Class 10. 1st div. Physical tools: United Kingdom 16 France 9; United-States 1: Prussia 1: Switzerland 1: Tuscany 1: Netherlands 1: Bavaria 1. 2nd div. Musical instruments: Great Britain 4; France 4; Bavaria 1. 3rd div. Clocks: France 2; Great Britain 1; Switzerland 1.

No medals were awarded for classes 11, 12, 13, 14 or 15.

Class 16. Shawls: France 1.

Class 17. Printing, binding and paper: the Imperial Viennese Printing House 1.

No medals were awarded for class 18.

Class 19. Rugs, lace, embroidery and so on: Great Britain 1; France 1.

For class 20 no medals were awarded.

Class 21. Knives and so on: Great Britain 1.

Class 22. Petty metal goods and so on.: Great Britain 5; France 4; Prussia 1; Bavaria 1; Belgium 1.

Class 23. Gold, silver and diamond objects: Great Britain 6; The German Customs Union 3; Russia 1.

Class 24. Glassware: France 1.

Class 23. Porcelain, pottery and so on: Great Britain 1; France 1.

Class 26. Furniture, wallpaper and so on: France 4; Austria 1.

Class 27. Processing of minerals: United Kingdom 2; the Papal States 1; Russia 1.

Class 28. Products developed from plants and so on: Great Britain 2; United States 1.

Class 29. Various products: France 2.

Class 30. Fine arts, sculpture, models and so on: Great Britain; 2 France 1; Prussia 1.

So ended this great industrial jubilee, which brought together representatives from all countries of the globe. What will happen now to the Crystal Palace? Will it remain in the same place, or will be dismantled into small parts? – On this there is still no positive information. (In any case, the exhibition building is so remarkable that we would like to offer some pleasure to our readers by presenting them with a view of its facade, which we await hourly from London.) It is said that a certain American, one Mr Barnum, recently arrived in London in order to buy the magnificent building World’s Fair from the British and move it to New York. Mr Barnum, apparently, is one of the most enterprising of people. He addressed his proposals to all the theatrical celebrities who were in London, inviting them to America. They say he was even invited Mme Bocarm to give several concerts in the major cities of the United States and Mexico, although Mme Bocarm in no way stands out for her artistic talent: she became famous only through the criminal trial with which our readers are already familiar. It is unknown whether these proposals have been taken up.

This translation by Sarah J. Young is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.