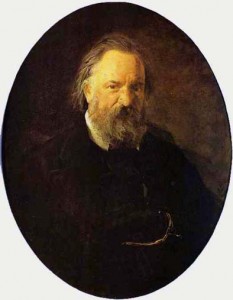

When researching the history of Russians in London, Alexander Herzen presents a considerable problem. He is without doubt the most significant of all the writers and activists who visited London in the nineteenth century, not only because he settled in the capital for some years (1852-64), but also because many of his compatriots — Turgenev, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Nekrasov, Pavel Annenkov, Vasily Botkin, Vasily Sleptsov — came specifically to see him. It’s certainly true to say that neither his closest friend Nikolai Ogarev nor Bakunin would have ended up in London if Herzen hadn’t been here. He is also the author of one of the greatest memoirs ever written, My Past and Thoughts, which is a massively important source on the Russian intelligentsia as well as being a very entertaining read. So he would seem like the ideal subject.

When researching the history of Russians in London, Alexander Herzen presents a considerable problem. He is without doubt the most significant of all the writers and activists who visited London in the nineteenth century, not only because he settled in the capital for some years (1852-64), but also because many of his compatriots — Turgenev, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Nekrasov, Pavel Annenkov, Vasily Botkin, Vasily Sleptsov — came specifically to see him. It’s certainly true to say that neither his closest friend Nikolai Ogarev nor Bakunin would have ended up in London if Herzen hadn’t been here. He is also the author of one of the greatest memoirs ever written, My Past and Thoughts, which is a massively important source on the Russian intelligentsia as well as being a very entertaining read. So he would seem like the ideal subject.

But for all the wealth of detail he presents, relatively little of My Past and Thoughts is devoted to his London life, and in general Herzen does not provide us with much commentary in other sources either. This may have been because he did not feel any rapport with the English, so failed to establish any real friendships, as Isaiah Berlin suggests. Perhaps, as London was the first long-term home he established after the disillusionment and failure of the revolutions of 1848, he was in no mood to seek out new acquaintances. Certainly, his description of his first days in London speak to preference for isolation: ‘I grew unaccustomed to others’; ‘Nowhere could I have the same hermit-like seclusion as in London’; ‘There is no town in the world which is more adapted for training one away from people and training one into solitude than London’ (My Past and Thoughts, pp. 445-7). According to Bernard Porter (Exiles, p. 43), such negative feelings about Britain were common among the political refugees who arrives after 1848 – most of them had no desire to be here.

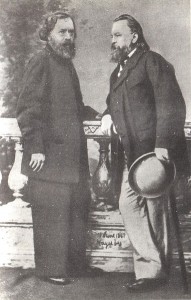

In London Herzen first lived alone, then with his own family, accompanied by the German writer Malwida von Meysenbug, who acted as housekeeper, governess and surrogate mother to Herzen’s children from 1853 (for more on her see Carol Deithe’s essay in Exiles). In 1856 the entourage was extended by the arrival of his old friend Nikolai Ogarev and his wife Natalia Ogareva, and ultimately by the children she had with Herzen.

Throughout his stay, Herzen moved around quite a lot, and a couple of his residences have proved slightly difficult to track down. After an initial stay at Morley’s Hotel, Trafalgar Square (Sobranie sochinenii 24, p. 321), by the end of August 1852 he had moved across Trafalgar Square to 4 Spring Gardens. He then found new lodgings in Primrose Hill (My Past and Thoughts, p. 445), at 2 Barrow Hill Place (Sob. soch. 24, pp. 356-7), and on the back of a letter to Maria Reichel he provides a handy (although in fact not particularly informative) sketch of the location. Towards the end of March 1853, he moved to 25 Euston Square (Sob. soch. 25, p. 33). He then moved out to Richmond, first taking lodgings at 3 St Helena Terrace (p. 191) by August 1854, then at Bridgefield Villas, Willoughby Road, Twickenham in October (p. 203), then Richmond House, Twickenham in January 1855 (p. 222), where 9 King Street is now. At the end of March 1855, he moved to Cholmondeley Lodge, 1 Cholmondeley Walk, Richmond; in his memoirs he recorded that Dr Vensky, ‘the first Russian who came to see us after the death of Nicholas [on 2 March 1855] … was perpetually amazed that it should be so spelt, but pronounced Chumly Lodge’ (My Past and Thoughts, p. 531).

In mid-September 1856, Herzen moved back into London, taking lodgings at 1 Peterborough Villas, Finchley Road (just North of where Swiss Cottage underground station now stands), and in a letter to Maria Reichel notes his sincere hopes that it would be his last move in London and that he still cannot get used to the city because of an ‘incompatibility of spirit’ (Sob. soch. 25, p. 318). But by mid-September 1856 he was on the move again, giving his address as ‘Mr Tinkler’s House, Putney’ (Sob. soch., 26, p. 26). From early February 1858 he used the address Laurel House, Putney. I’ve not managed to locate either house. Carr (p. 189) states that these are the same residence, on High Street, Putney, but if that is the case, I wonder why Herzen changes his manner of addressing letters for the last months of his stay. On 24 November 1858, he wrote to Jules Michelet to inform him that he had moved to Park House, Percy Cross, Fulham (p. 226). Percy Cross, also known as Purser’s Cross, is, according to British History OnLine, on the Fulham Road between Parson’s Green and Walham Green. In May 1860 he was living at 10 Alpha Road, Regent’s Park (Sob. soch., 27.1, p. 52). Presumably this is now the cul-de-sac named Alpha Close, to the west side of Regent’s Park. In November 1860, the menage settled at Orsett House, Westbourne Terrace, near Paddington Station. The house is still there (it was renamed Brunel House at some point), but although it looks as though the outside was fairly recently renovated, it is partially boarded up and gives no indication of its famous former resident and his visitors. [Note: since I posted, I have realized I have a picture of the wrong house, and Herzen’s house is in fact round the corner, with a blue plaque – the Complete Works makes the same error, strangely, with an old picture which I assumed came from Herzen’s papers, and this is what confused me. I’ll take a picture of the real Orsett House when I’m in Paddington without rushing for a train, and post that.]

The Herzens remained at Orsett House until June 1863, and then moved out again to Elmfield House, Teddington, where they lived for just over a year (p. 348). This is now a dental practice, and it seems to be fairly well established that Garibaldi, on his three-day trip to London in 1864, visited Herzen there. Returning to London in September 1864, Herzen lived at Tunstall House, Warwick Road, Maida Hill (Sob. soch. 27.2, p. 512) – is this Warwick Avenue? His final London address two months later is 11 Eastbourne Terrace, which runs parallel to Westbourne Terrace, but he was there only a matter of days (pp. 521-6). The extended family was breaking up, in part because of the arrival of twins to Herzen and Ogareva, and a return to Europe became inevitable (Carr, pp. 248-9). Herzen returned for a couple of weeks in late February 1865, staying with Ogarev at 6 Rothsay Villas, Richmond, but departed for good on 15 March 1865.

After his initial lonely days, Herzen was certainly not short of company. He seems to have made few English friends, although he sought acquaintance with Thomas Carlyle soon after arriving in London and visited the Carlyles’ house at 24 Cheyne Row, Chelsea (this letter from Jane Carlyle dated 15 September 1852 mentions one such visit from the evidently rather exotic seeming guest, and introduction to volume 27 of the Carlyle letters gives more details of their encounters in 1852).

But his life continued to be conducted mainly in Russian circles. In addition to being joined by Ogarev, Herzen was visited by a great many Russians during their European travels – on Sundays, the Herzen household was definitely the place to be. I’ll be publishing separate posts in the coming weeks about the short visits of Tolstoy (March 1861) and Dostoevsky (July 1862), Turgenev’s regular stays London while Herzen was based here, and the year or so that Bakunin spent here (December 1861-April 1863). Herzen features prominently in all these stories. Among other literary figures, he was also visited by Chernyshevsky in 1859 (very little is known of this trip), Nekrasov, the poet and editor of the journal Sovremennik (The Contemporary), in 1857, and at various points by the critics Pavel Annenkov and Vasily Botkin (Waddington give numerous details beyond the Turgenev-Herzen relationship). He also regularly received and gave assistance to an assortment of impecunious Russians – the story of his encounters with Prince Yuri Nikolaevich Golitsyn is very wittily told in My Past and Thoughts (pp. 539-49).

Nor, despite his change of heart following the disappointments of 1848, did Herzen abandon revolutionary circles, and he regularly saw fellow exiles living in London, such as Giuseppe Mazzini, Louis Blanc, and other visitors, such as Armand Barbes (My Past and Thoughts, p. 453). It was through these figures, according to Carr, that Herzen was drawn out of his isolation to speak at public meetings for his cherished causes. On 29 November 1853 he spoke at the Hanover Rooms (presumably in Hanover Square) to celebrate the anniversary of the Polish insurrection of 1830, and on 27 February 1855, he participated at a meeting at St Martin’s Hall, Long Acre, to commemorate the 1848 revolutions. Marx, who harboured a long-standing antipathy towards Herzen, turned down an invitation to the event as he would not share a platform with Herzen (Carr, pp. 139-40). However, such engagements were few and far between, and Herzen remained essentially a private figure.

Nor, despite his change of heart following the disappointments of 1848, did Herzen abandon revolutionary circles, and he regularly saw fellow exiles living in London, such as Giuseppe Mazzini, Louis Blanc, and other visitors, such as Armand Barbes (My Past and Thoughts, p. 453). It was through these figures, according to Carr, that Herzen was drawn out of his isolation to speak at public meetings for his cherished causes. On 29 November 1853 he spoke at the Hanover Rooms (presumably in Hanover Square) to celebrate the anniversary of the Polish insurrection of 1830, and on 27 February 1855, he participated at a meeting at St Martin’s Hall, Long Acre, to commemorate the 1848 revolutions. Marx, who harboured a long-standing antipathy towards Herzen, turned down an invitation to the event as he would not share a platform with Herzen (Carr, pp. 139-40). However, such engagements were few and far between, and Herzen remained essentially a private figure.

He made the decision to stick solely to intellectual and propaganda work. This led to the foundation of the Free Russian Press, with offices first at 2 Judd Street and later at Thornhill Place, Caledonian Road. The latter offices were visited by a journalist from the Saturday Review, who was startled by the exotic atmosphere: ‘the rooms which they occupy are pervaded by so thoroughly Slavonic an air that a visitor might imagine that they had been suddenly transported to Moscow or Petersburg. Russian books occupy the shelves, Russian proof-sheets cover the tables and Russian manuscripts are being set up by the compositors whose speech is Russian or Polish’ (cited in Partridge, pp. 460-1).

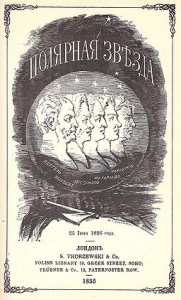

Two very important publications came out of the Free Press, the almanac Poliarnaia zvezda (The Polar Star, 1855-62 and 1869) and the journal Kolokol (The Bell, 1857-67). Poliarnaia zvezda was an annual publication which featured writings by Herzen and Ogarev, but also a large number of works by Decembrists (Ryleev, Bestuzhev, Lunin, etc) unsurprisingly, as it was a revival of the Decembrists’ almanac from the early 1820s and had their images on its cover. There were also contributions by European radicals and revolutionaries (Michelet, Mazzini, Proudhon), and works that could not at the time be published in Russia, such as Chaadaev’s First Philosophical Letter.

Kolokol started out as a supplement to Poliarnaia zvezda, but became the more influential publication. In My Past and Thoughts, we read: ‘”The Bell is an authority,” I was told in London in 1859 by, horrible dictu, Katkov’ (p. 533), and if such a reactionary figure was prepared to admit this, it must have been very popular indeed. Large numbers were smuggled into Russia (I’ve seen references to print-runs of 3,000-5,000), and it was pretty much required reading for everyone from radicals to government officials at the highest level. It featured literary works and articles on contemporary conditions in Russia – you can download it here. Its influence began to wane after a split with the liberals that followed the emancipation of the serfs, but it was really Kolokol’s support for the Polish uprising of 1863 – as a result of friendship with Bakunin and probably against Herzen’s better judgement – that its popularity really declined.

Nikolai Ogarev

I’m not intending for the moment to write a separate post on Ogarev. This is mainly because his life in London was so bound up with Herzen’s, both professionally, in their work on Poliarnaia zvezda and Kolokol, and privately, not only in the closeness of their friendship, but also in the unhappy menage-a-trois with Ogarev’s wife Natalia that began not long after the couple arrived in London. So there would be very little different to say. But it’s also a reflection of the fact that in scholarship, as in life, Ogarev has been overshadowed by his more famous friend. For anyone who’s particularly interested, Carr’s The Romantic Exiles contains a couple of chapters on Ogarev, though I feel they’re not helped by his vicious assessment of Natalia Ogareva. Perhaps she deserved it, but a little more detachment would have been welcome.

Nevertheless, a few details are worth noting. After Natalia Ogareva took up with Herzen, her husband’s position within the household was precarious, and Ogarev frequently took lodgings elsewhere, only to return to Herzen’s and then move out again. According to Carr (p. 337), he lived at various times in Richmond, Sydenham, Putney and Wimbledon. In 1858 Ogarev fell in love with Mary Sutherland, a prostitute he met in a pub (he was always a heavy drinker). He installed her and her son Henry in a flat in Mortlake and supported them for the next six years. When he left London for Geneva, Mary travelled with him, and they lived there separately at first, but later together. They returned to Britain in 1873, and lived together in ‘small house in a mean street’ in Greenwich (Carr, p. 344). Ogarev died in 1877 and was buried in the cemetery on Shooter’s Hill, now Greenwich Cemetery (Carr, p. 346). His grave was still visible when Carr was writing the book in the early 1930s, but his ashes were later reinterred in Novodevich’e cemetery, Moscow.

I have annotated my Russians in London Map with places associated with Herzen and Ogarev (marked in yellow). The scattering of markers, mainly over West and North West London, is quite striking, particularly as most denote places where Herzen and his extended family lived. It suggests to me a constant sense of discomfort, of never feeling at home, and always looking for somewhere better. Perhaps this is what life as a political exile meant. For Ogarev, I have only been able to include some very general markers, as I do not (yet) have more detailed information. But the places I have been able to mark are notably in the suburbs, and at a considerable distance from where Herzen was living (and with a definite preference for South London!). When Ogarev returned to England in 1873, maybe he chose to live in Greenwich because of Mary’s connections, as Carr suggests. Or maybe he still preferred to remain as far as possible from the London he associated with his friend, even after the latter was dead and gone.

Sources

Isaiah Berlin, The Great Amateur, New York Review of Books, 14 March, 1968

E. H. Carr, The Romantic Exiles: A Nineteenth-Century Portrait Gallery (London: Victor Gollancz, 1933)

Carol Deithe, ‘Keeping Busy in the Waiting Room: German Women Writers in London following the 1848 Revolution, in Exiles from European Revolutions: refugees in mid-Victorian England, ed. Sabine Freitag (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2003), 253-74

Elena Dryzhakov, ‘Dostoevskii i Gertsen: Londonskoe svidanie 1862 goda’, Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 17.3 (1983), 325-48

A. I. Gertsen, Sobranie sochinenii v tridtsati tomakh (Moscow: Nauka, 1962)

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts, trans. Constance Garnett (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1982)

Monica Partridge, ‘Alexander Herzen and the English Press’, The Slavonic and East European Review, 36, no. 87 (June 1958), 453-70

Bernard Porter, ‘The Asylum of Nations: Britain and the Refugees of 1848’, in Exiles from European Revolutions: refugees in mid-Victorian England, ed. Sabine Freitag (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2003), 43-56

Patrick Waddington, Turgenev and England (London and Basingstoke: MacMillan, 1980)

My thanks to Carol Davies Foster from Education, Children’s and Cultural Services, London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames, for information on the precise locations of Richmond House and Bridgefield Villas in Twickenham.

Richard Ekins

/ December 31, 2011Sarah, I would very much like to be in contact with you. Your piece on Lenin was very useful to me in getting the Marchmont Association to agree that their Blue Plaque scheme should honour Lenin’s stay in Tavistock Place. Do you have more details on the Free Russian Press’s residency in 2 Judd Street – now Hunter Street, and I think demolished to make way for the building that now houses the School of Pharmacy? I’m seeing if there is a case for a Marchmont Association Blue Plaque there, too.

Nick Owen

/ December 31, 2011Your article is very interesting.

I am trying to find out more about Mary Sutherland’s relationship with Ogarev. I believe that Mary had a son Henry but I do not know who was the father, Ogarev? I am related to Mary Sutherland but I am not exactly sure of the exact family tree or who Henry grew up to be. Do you have any more details on whether Ogarev fathered Mary’s son?

Many Thanks

Nick Owen

Sarah Young

/ January 2, 2012Richard – many thanks for this, and I’m very pleased to hear about the Tavistock Place plaque. I don’t have anything else on the Free Russian Press at present, but I’m researching it intermittently, and this certainly gives me an incentive to keep digging. You can contact me via my SSEES email, s.young [at] ssees.ucl.ac.uk, or my home address, sarah [at] sarahjyoung.com.

Sarah Young

/ January 2, 2012Thank you for this – what an interesting family connection! The best source I have is E. H. Carr’s The Romantic Exiles (problematic in many ways but quite sympathetic to Ogarev, if somewhat condescending about Mary Sutherland), pp. 291-305. In the letters quoted, Ogarev almost always refers to Henry as ‘the boy’, and there is no indication that he is the father, although he did pay for his education. Ogarev and Mary met in 1858, so I don’t know whether that helps – do you have a date of birth for Henry? I’ll have a look at some of the sources in the library when I have a spare moment, and see if they can shed any further light on the question.

best wishes,

Sarah

Richard Ekins

/ January 7, 2012I now see that Herzen wrote a book on the Free Russian Press in London. Desiatiletie Volnoi Russkoi Tipografi v Londone: 1853-1863 [Ten Years of the Russian Free Press in London, 1853-1863] London, 1863. I don’t read Russian, but presumably this book provides confirmation of the address and may give actual dates at 2 Judd Street – ?month 1853-? month 1855. Yes?

According to E.H. Carr, Romantic Exiles: ‘in the spring of 1853, the Free Russian Press was installed on the premises of the Polish Press at Regent Square. It was afterwards transferred to premises of its own, first in Judd Street, and later at Thornhill Place, Caledonian Road.’

Does anyone know the precise dates? Also, it would be nice to know the actual Regent Square address. Was this a different place to the sordid squat for revolutionaries in Regent Square often referred to in the literature.

Sean Mitchell

/ January 17, 2012Hi Sarah

thank you for putting this wonderful website together. I am a former Russian Studies student who recently qualified as a London Blue Badge Guide and have a great interest in London’s Russian connections – I have been trying to get people interested in Herzen because, as you indicate in your article, not only is he a fascinating figure in himself but he was at the centre the world of the post-1848 European emigres which is an undertold chapter in London’s history – but he is such an obscure figure for 21st century Londoners that it’s an uphill struggle. I’m also trying to find out where the very first press was on Regent Square and would be grateful for any leads you have got.

I’m afraid, however, I do also have a correction for your article on Herzen as well; you have made a mistake in the text based on the fact that you seem to have identified the wrong house in your Paddington photograph: Herzen’s house was the one round the corner actually on Orsett Terrace – not this one on Westbourne Terrace. When you walk down Orsett Terrace from the Westbourne Terrace end, his house was the first on the left and on the far side (from the direction you are walking) past the entrance you will, in fact, find the only blue plaque recording his life in London.

I look forward to reading more articles about London’s Russian connections.

Regards

Sean

Sarah Young

/ January 17, 2012Sean –

Many thanks for this. I hope you’ve seen the comments to this post by Richard Ekins, who is also interested in Herzen’s London connections and the Russian Free Press for blue plaque purposes. I will do some more research when I have a bit more free time and see what I can come up with from his letters etc – at the moment I’m snowed under with marking and preparing exam papers!

I realized I had a photo of the wrong house very soon after I posted it – my confusion was caused by the Complete Works of Herzen, which, bizarrely, contains a reproduction of an old (ie roughly from the time of Herzen’s residence) photo of the wrong building. I’ve been meaning to replace it, but I’m only ever in Paddington when I’ve got a train to catch and have too many heavy bags with me. But thanks for the reminder – I will get round to it soon!

Sean Mitchell

/ January 23, 2012Hi Sarah

I’m glad I could be of help – perhaps another photo of the actual house taken at the right angle to get in the Blue Plaque would make a really good starting point for Herzen pilgrims checking out your site – time permitting of course – I know exactly what you mean!

I would like to ask you for some clarification on another of his residences that I’m really keen to track down: can you tell exactly where the reference is to 2 Barrow Hill Place – I have not got access to the Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii and so I need to know exactly which work it is in my shortened Russian sobranie or in my English translations.

Also, I tried to find this address yesterday but, as I am sure you know, there is only a very truncated Barrow Hill Road now so do you have any further information about whether “Number 2” was at the Primrose Hill end of this road (which has now disappeared) or at the St John’s Wood end which still exists? I will be pursuing this when I have more time and if I do manage to find out exactly where the house was I will, of course, let you know so it can be posted on your site – this, after all, was where he started writing Byloe i Dymy. Thanks.

Sean

Richard Ekins

/ January 23, 2012Good to see this thread progressing. Assuming we can get firm evidence that 2 Judd Street was the address of the Free Russian Press between 1853-1855, we then have to locate the precise site. It seems that in Herzen’s day, the stretch of Judd Street between Leigh Street and Tavistock Place was then Hunter Street. So Judd Street stopped at Leight Street. It might seem as though no. 2 would be where the open space/dog space is, but I have no firm evidence as yet. Some say it might be near the North West corner of Cromer Street. I’ll report progress as I get it, but I am hopeful we will get a Marchmont Association Blue Plaque if we can pinpoint a site as the actual site of the Free Russian Press – subject to permission, of course, of the present site owner, or, in certain circumstances, an adjacent site owner.

Best wishes with your exam period.

Richard

Sarah Young

/ January 23, 2012Yes – it’s great that this is developing! I should have some time next week to do some work on this and confirm addresses, so I’ll be in touch then.

Sarah

Richard Ekins

/ January 25, 2012Thank you , Sarah. With the help of Ricci de Freitas, I think we have now located the precise spot of the old No. 2 Judd Street. I will email you the maps. So we just need confirmation/evidence that No. 2 is right and the time of occupancy which I feel sure was 1853-1855.

Sean Mitchell

/ January 26, 2012Thank you Richard for all your work on this issue – it would be wonderful to see another plaque apart from the one on the house in Paddington reflecting Herzen’s life in London and I can’t wait to find out where you have identified the location on Judd Street having been very disappointed on a recent visit to find no contemporary evidence of a No. 2.

Do you have anything further on the very first location of free Russian publications at the Polish Press on Regent Square? I found one lead saying that Herzen published through the same press that produced “Polski Demokrati” which I’m assuming must be the Polish Press on Regent Square if the E.H. Carr reference is correct. Thanks.

Sean

Richard Ekins

/ January 26, 2012Sean, maybe you know this book: Alexander Herzen and the Free Russian Press in London: 1852 to 1866 by Francoise Kunka (Paperback – 6 Mar 2011). Interesting, but possibly doesn’t take our quest any further than Carr. It is Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association, who has pinpointed the relevant 2 Judd Street – to my satisfaction, at any rate. It is where the dog park/toilet is now – a little south of the Leigh Street entrance – on the opposite side from Leigh Street. On your last query, again, no one seems to give the actual number in Regent Square where the Polish press was. The number is, of course, given for where the Russian revolutionaries used to hang out – that Lenin avoided staying at because of the noise and squalor. But I’m assuming – maybe wrongly – that that was a different address. Quite a happening place Regent Square, at the time!

Sarah Young

/ January 31, 2012Sean – 2 Barrow Hill Place is, I think, a very difficult place to track down. In Byloe i dumy, part 6, chapter 1 (Londonskie tumany), Herzen just refers to ‘beyond Regent’s Park, near Primrose Hill’ (PSS XIV, p. 10; My Past and Thoughts, trans. Constance Garnett, abridged Dwight Macdonald (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1982), p. 445). It’s the letters that give more detail: vol XXIV, p. 356 has the unhelpful map I refer to in my post – I can scan a copy of this for you if you can’t access the Complete Works yourself – but it does contain a note saying there is ‘an endless view of the park’ from the window, and then letters on pp. 357-366 (nos. 234-8, 1-21 November 1852) have the address 2 Barrow Hill Place, Primrose Road. Subsequent letters have no address, but that is not unusual when he’s dealing with his normal correspondents.

Richard – I have made progress with the 2 Judd Street dates, details of which I’ve sent you by email (I want to write it as a post rather than having it hidden away in a comment).

On the Regent Square question I have no further information – I don’t know whether it was the same place as was later used by revolutionaries, nor have I found any clues to a precise address. There are references in Herzen’s letters from 1853 (vol 25 of the Complete Works) to the press being shared with the Poles (e.g. letter 96 to Michelet (pp. 120-22), which confirms Carr’s reference, but doesn’t take us any further forward.

Sean Mitchell

/ February 2, 2012Hi Sarah and Richard

Thank you for your most recent up-dates on the Herzen Trail – I’ll be visiting Judd Street again, Richard, armed with your instructions.

With regard to the Primrose Hill site, I have got hold of a map of London in 1850 and, although it has completely disappeared now, Barrow Hill Place is clearly marked with a set of what appear to be 6 houses arranged around it. Going on the principle that house numbers go up as you get further from central London, Number 2 would indeed have been at the eastern end of this little pocket of houses giving a view over Primrose Hill Park as your letter from Herzen indicates, Sarah.

The site of the Close is between where St. Edmund’s Close and Ormonde Terrace are today and having tried to orientate myself in relation to the covered reservoir which was up on Barrow Hill in 1850, based on the suppositions given above, I would say his house was probably in the middle of what is now Ormonde Terrace. However, I’m still in the process of confirming my supposition about the house numbering.

Sarah – if you can, I would really appreciate a scanned copy of the letter where he refers to this address and, if it’s convenient to do the map, that would be great as well. I will email my address to you on your SSEES address.

Finally, are either of you aware of any celebrations of Herzen’s birthday this year – after all, like Dickens, he’s 200 years old!

Regards

Sean

Phoebe Taplin

/ February 8, 2012Thanks for all the wonderful, meticulous and constructive research and comments! I don’t know about Herzen birthday events here in London, but Sean’s comment reminded me that when I last popped into the dilapidated Herzen museum on Sivtsev Vrazhek in Moscow, it was shut for remont and they said it would reopen in 2012 – maybe by way of celebration?

Sarah Young

/ February 9, 2012Thanks Phoebe – glad to hear the Herzen museum is being refurbished (I seem to remember it being a bit shabby when I visited, and that was more years ago than I care to recall!). I’ll be writing a new post or two in due course to collate all the new findings…

Richard Ekins

/ February 9, 2012Please take with care some of the detail as to precise places and dates in my posts. Thanks to Sarah’s further work, we are near to coming up with something definitive.

Hilary Chapman

/ February 12, 2012I was interested to read the comments from Nick Owen about his link with Mary and Henry Sutherland as I have found out some information about them in the course of my research on Ogarev in England. Henry Knight Sutherland was born on 28 July 1851 at St Martin in the Fields Workhouse. The name of his father does not appear on his birth certificate but 1851 was 5 years before Ogarev arrived in London. The full name and birth date are used in a draft letter by Ogarev, perhaps written for offical purposes, and published in a Russian translation. In Geneva with Mary Sutherland and Ogarev, Henry Sutherland studied clock-making first and then the natural sciences, before working as a tutor and studying further in Kiev. In 1887 he presented a doctoral thesis in medicine in Paris.

Also, about the Free Russian Press at 2 Judd Street. It remained there until the end of February 1860, when it moved to 5 Thornhill Place, Caledonian Road. The address was printed at the top of copies of “Kolokol” and the moved announced in “Kolokol” no. 63 of 15 February 1860. I hope this helps with the blue plaque campaign!

Sarah Young

/ February 12, 2012Many thanks for this! The information on Henry Sutherland is really useful and confirms my assumption – he was obviously an interesting figure and went far from very humble beginnings in a workhouse! You’re right about the move away from Judd Street – we’ve now established the different addresses of the Free Russian Press but are still in the process of confirming some actual locations because of changes of numbering etc. I’ll be writing a post collating all the information soon.

Sean Mitchell

/ February 24, 2012At the risk of revealing what an exact location ‘anorak’ I am, I am very keen to pin down the precise positions of the various Herzen sites. To that end, I have some research results to share but also a question in response to Hilary’s information.

The very first Free Russian Press on the premises of the existing Polish Democratic Press at 38, Regent Square was on the north side of the square directly opposite where No. 6 is on the south side of the square today. So by my reckoning that puts it just to the right of the entrance to the eastern unit of the current Rodmell council blocks; the houseline started just behind the pavement, as on the south side today, so that puts the entrance, to what seems to have been one of the standard terraced houses, where the large, unkempt shrub to the right of the entrance steps in the front garden strip is today.

Herzen’s Primrose Hill residence, where he started writing “Byloe i dumy” in the autumn of 1852 was almost on the same houseline just to the right (or the east) of the double glass door entrance to the current Consort Lodge next to Wells Road.

I am looking forward immensely to getting Richard’s final confirmation of the exact location of the 2, Judd Street site – here’s to hoping that it’s not in exactly the same place as the dog toilet area!!!

However, my question is in regard to the third site of the Free Russian Press: where is Thornhill Place??? The Ordnance Survey map for 1871 has a Thornhill Bridge Place, Thornhill Street and Thornhill Bridge – but nothing corresponding exactly to this address. Moreover, the edition of “Kolokol” for July 1st 1862 gives the address as 136 & 138 Caledonian Road – do they mean round the corner on one of the “Thornhill” variants or was it located on the main road at some stage???

I’d be grateful for any feedback. Thanks.

Sean

Hilary Chapman

/ February 27, 2012I’ve checked the censuses for 1861 and 1871 to see if they help with Sean’s query.

In the 1861 census Louis Czerniecki, born in Poland, a printer employing 7 men was at 5 Thornhill Place. I assume this was Ludwik Czerniecki whose Polish printing press accommodated the Free Russian Press. By 1871 he, along with Herzen and Ogarev, had left London for Switzerland, but I checked some other 1861 residents of Thornhill Place and found that, for example, Frederick Moore of 6 Thornhill Place was at 134 Caledonian Road in the 1871 census and Thomas Williamson of 4 Thornhill Place was at 140 Caledonian Road–and presumably 5 Thornhill Place somehow became 136 and 138 Caledonian Road. This might suggest that Thornhill Place did become part of Caledonian Road, though the 1871 numbering may not necessarily be the same as today–if 136 and 138 still exist.

Richard Ekins

/ March 3, 2012Sarah will be posting a full update. She has pinpointed the addresses and dates of the TWO Judd Street addresses of the Free Russian Press. While 2, Judd Street is, indeed, in the area of the dog walk, this was, in fact, the second Judd Street address. The first Judd Street address – after 38, Regent Square (thank you, Sean) – was 82, Judd Street. I have just located this as the present 61, Judd Street, thanks to the LCC Survey of London, Vol. XXIV, King’s Cross Neighbourhood – The Parish of St. Pancras, 1951, Part IV. Pp. 82-87 sets out the relevant details. After commenting on various street name changes, it states: ‘The only buildings left between Tavistock Place and Leigh Street are Nos 61, 63, and 65 on the west side (present numbering). The details set forth on p. 85 make it possible to deduce with certainty that the present No. 61 was the previous No. 82.

Sarah Young

/ March 5, 2012Sorry I’ve been silent for a while – I’ve had pneumonia, and when I have been fit to work, I’ve been working on a conference paper. I will indeed post a full update, but that’s probably not going to be ready until Herzen’s anniversary, as I’m going to be very busy catching up with work and with a couple of conferences before then. And there are still a few things I want to check out and some details to bring together from the various emails we have exchanged. So this is just to say thank you to all three of you for your hard work and contributions to this question. 5 Thornhill Place is definitely the correct address following the move from Judd Street – I’ve seen this in various places – and Hilary’s suggestion that this was renumbered to be 136-138 Caledonian Road seems likely (I will check this at some point). This means, I think, that we have all the locations for the Press, and have clarified a couple of things re Herzen’s homes as well.

Richard Ekins

/ March 7, 2012Sarah, so sorry to read of your illness. I have emailed you. For your recovery – this is a particularly good ‘find’. It dates the actual start of the Free Russian Press. It makes it quite clear that it is regarded as a separate enterprise from the previous collaboration with the Polish Press at Regent Square. More particularly, it dates with precision the start of the operatiion.

See also:

http://www.archive.org/details/bibliographyofpr01bigmrich

IMPRIMERIE RUSSE a Londres. London : 1854. Single sheet 4to.

A circular, in French, was issued in

February, 1853, announcing that it was in-

tended by the Russian refugee, A. Herzen,

to set up a Russian press in London, “to

afford a free tribune for Russian thought,

and to expose the monstrous acts of the

government of St. Petersburg.” All

Russians “who loved their country, and

at the same time loved liberty,” were in-

vited to send in their manuscripts. These

were to be printed at the expense of a

fund provided for the purpose, as it was

believed that their publication would be-

come a propaganda of a very effective

3

character. The circular above cited states

that the project had been realized. Since

the ist of June of the preceding year the

press had been at work, notwithstanding

the great difficulties resulting from the

war which was then being carried on.

Friends of the “democratic centralization

of Poland” had circulated these publica-

tions throughout Europe, from the banks

of the Black Sea to the shores of the

Baltic. The press was situate at 82, Judd

Street, Brunswick Square. At the back

of the circular is a list, printed in Russian

and French, of the works already issued.

A

362 Bibliography of Printing.

Richard Ekins

/ March 7, 2012Correction. The original note about this publication can be read on p. 361 of the Bibliography of Printing – see link. I could not copy this original text and was working from another source. Apologies!

Hilary Chapman

/ March 9, 2012I hope you’re feeling better now, Sarah. I don’t know whether you are also looking at the later London site(s) of the Free Russian Press, but from July 1863 its address was given (in Kolokol) as Elmsfield House, where Herzen etc. had moved. However, in her memoirs, Tuchkova-Ogareva wrote that Czerniecki and the printing press had moved to a small house about 10 minutes’ walk away. From July 1864 (when Herzen left Elmfield House) until the final edition of Kolokol published in England, the address of the press was given as Jessamine Cottage, New Hampton, Middlesex. Perhaps that was where the press actually went after Caledonian Road. I wonder whether that address is still there?

Sean Mitchell

/ March 9, 2012Sarah – I am very sorry to hear you have been ill – I wish you a speedy and complete recovery!

Thanks to you and Richard for the additional Judd Street info – I’m very glad to hear there’s another Judd Street address apart from the dog toilet area – somehow that dark, little, officially-manured corner doesn’t inspire associations with Romantic revolutionaries!

Thanks to Hilary for the intriguing details about Elmsfield House and Jessamine Cottage. I’ve come across a reference to the latter, but because it didn’t appear to come up any where else, I didn’t think any more of it. But now you have inspired me to go and check this location out at some stage.

I’ve been focusing on Ogarov recently: I’ve felt for a long time that there is a rather poignant historical symmetry in the fact that he ended up in Greenwich where Peter the Great initiated the whole theme of Russians in London.

Well, it turns out that Ogarov lived very close to the site of Saye’s Court (and even closer to the Peter the Great monument on the river walkway) in what is now Ashburnham Place. He lived at No. 35 which is a mid-Victorian Gothic Revival Style house from the 1860s that, wonderfully, is still there!

I tracked his address down starting from his gravestone in Greenwich Cemetery. It’s also still there (although, as you know the body was taken back to the USSR in 1966) but this info is recorded on the stone and is another bit of Russian London history in itself because he apparently briefly laid in state in the Soviet embassy.

Sarah – I can e-mail you a photo of the gravestone itself as well as an aerial photo indicating the exact location within the cemetery along with a map for your website if you think Herzen’s Circle pilgrims will want to venture out to Shooter’s Hill. Thanks.

Sean

Sarah Young

/ March 10, 2012Richard, Sean, Hillary – Many thanks for your latest messages. I’m much improved, sufficiently so to go to a conference, so will respond to these latest details properly when I’m back later in the week.

Richard Ekins

/ March 10, 2012Sarah- good news about your recovery. Thank you so much for your new information Hilary. It seems that the notice I found wasn’t as definitive as I had hoped. You will appreciate that my limited aim, right now, is to establish with certainty whether the move to 82 Judd Street should be dated to 1853 or 1854 (or 1855, ? not likely) – for the purposes of a blue plaque. The title page of the first edition of The Polar Star is dated 1855 and says ’82 Judd Street, Brunswick Square’. It would be great to hear from any of you guys who have title page details with ’82 Judd Street’ and 1853, or 1854, on them.

Richard Ekins

/ March 10, 2012Incidentally, Sarah, when you are able to respond, I do hope you will leave this thread, as it stands, as it makes a nice record, amongst other things, of my fumblings, and collaborative research in the age of the internet.

Richard Ekins

/ March 10, 2012During the first two years of the Free Russian Press, Herzen published his own works, such as St. George’s Day! St. George’s Day!, The Poles Forgive Us!, and Baptized Property. If anyone could access the title pages of these publications, they may help date the move to the 82, Judd Street address. Do they have the date and place of publication?

Richard Ekins

/ March 10, 2012Specifically, here is a related lead, seemingly translated from a Russian student paper, but it sounds very authoritative:

‘Freestyle printing press was established June 22, 1853. Within days of the first edition brochure “St. George’s Day! George’s Day! n

Nobility “, in which Herzen calls on . . . In late July 1853, Herzen prints and publishes a proclamation under called “Poles forgive us!” . . . In August 1853, Herzen publishes his pamphlet “Baptism property”, directed against serfdom.

My question is what printing address – if any – do these publications have? Can anyone help?

Hilary Chapman

/ March 11, 2012I haven’t got the title pages of Herzen’s early publications in London, but I have found some details that might answer Richard’s query.

In Herzen’s memoirs Byloe i dumy (Collected works vol XI, 142) he refers to a meeting of the Polish émigrés on 29 November 1854, and then he goes on to write that ” … at the same time I had to move the Russian press to another place.” It seems that the man who rented where the presses were was in debt and Herzen was worried that his press would be seized.

Also in a draft letter in French to the Polish émigré leader S Worcell on 22(10) December 1854 Herzen wrote: “… le changement du local de l’Imprimerie russe n’a été motivé que par des considérations purement économiques. …Rien n’est change dans nos rapports—seulement nous avons deux imprimeries, au lieu d’une.” (XXV, 220)

From those quotes it looks as though the move to Judd Street took place towards the end of 1854. If I come across anything else to support that (or not) I’ll post that.

Richard Ekins

/ March 11, 2012Hilary, this is very helpful. Indeed, it fits with our line of thought before I came across the publication dated 1854 that I referred to above: IMPRIMERIE RUSSE a Londres. London : 1854. Single sheet 4to.

Could it be that this latter publication was printed in December 1854, so was able to include the 82 Judd Street address, rather confusingly suggesting the start date there was 1st June 1853 when in fact that start date was at 38 Regent Square? Also, confusingly, the start date at Regent Square is usually said to be ‘Spring’, when, in fact ‘Spring’ in the UK is usually said to be March/April/May! Yes, do please let me know of anything further you come across.

Richard Ekins

/ March 14, 2012The thin and often bad scholarship on Herzen and the Free Russian Press in London is exasperating! Having been sent on a wild good chase by Kunka’s wrong dating of the move to Caledonian Road, I have just read this in Kate Sealey Rahman, ‘Russian Revolutionaries in London, 1853-70: Alexander Herzen and the Free Russian Press’, in the very scholarly Foreign-Language Printing in London 1500-1900 (ed.) Barry Taylor, 2002. Having given new – to me – information on the situation at 38 Regent Square, she writes: ‘Yet when, forced by fears that Zienkowicz’s failure to pay his debts would lead to the seizure of the press, Herzen decided to move the Russian printing press into its own premises – first at Number 2 and then Number 82 Judd Street , and later to premises on the Caledonian Road . . . THIS CANNOT BE RIGHT, SURELY!

Hilary Chapman

/ March 16, 2012I’ve just come across the following, which seems to confirm the 82 then 2 Judd Street order, without giving any dates for the change. Vol. XII of Herzen’s Collected Works contains his early works published in London, including a short article dated 25 March (6 April) 1855 announcing Poliarnaia zvezda. Page 493 of the volume notes some variations between the first and second edition of this announcement, including that the first edition, at the end states that manuscripts can be addressed directly to the editor “or to the Russian press M.L. Czerniecki—82 Judd Street, Brunswick Square, London.”, while the second edition has “… or to the Russian press M.L. Czerniecki—2 Judd Street, Brunswick Square, London.” As I say, though, it doesn’t help with any dates.

Richard Ekins

/ March 16, 2012Thanks for this, Hilary. We are all awaiting Sarah’s definitive report – it was she who alerted me to the order which you have kindly confirmed. I think that for blue plaque purposes, we can safely say 1854-1857 are the dates at 82 Judd Street. It would be nice, however, to have yet more evidence confirming that it could not be 1853-1857.

Sarah Young

/ March 18, 2012Everything I have seen, including, most importantly, dates and addresses on original publications, confirms the 82 then 2 Judd Street order, so I think we can assume that Sealey-Rahman just got this the wrong way round (she was not the only one). I think I have finally tracked down fairly firm dates for everything up until the move from 5 Thornhill Place in 1863, with more than one piece of evidence in each case. There are still one or two things I want to track down, so rather than detailing them here in the comments now, I wil put everything together a post. Unfortunately, because I’m still catching up with teaching after my illness, and have the BASEES conference coming up (which involves a large amount of work because I’m Secretary), that may not be finished for a couple of weeks – in fact it may well end up being my post to mark Herzen’s anniversary.

Richard – I’ll try to have a look at the document you sent me this week and write to you separately about that.

I’m also keen to make sure this comment thread is preserved as a record of our research – it will remain here on my blog, but I also plan to collate everything and, if you are willing, add the relevant parts of emails we have exchanged on the subject, and make it available as a pdf.

Richard Ekins

/ March 18, 2012Great, Sarah. Glad you are recovering. Do you think you will have your ‘final’ confirmation of the 82 Judd Street dates in time for the Marchmont Association meeting in April? It’s not crucial if you haven’t, as I wrote, but it would be nice. I may be away from email contact 23rd-28th March. Looking forward to the pdf. I am willing – very!

Sean Mitchell

/ March 29, 2012Hi All

I’ve finally managed to go through the postal directories for the times and places we are interested in and what I discovered seems to bear out quite a lot of what we are assuming.

The registered addressee for 38 Regent Square in 1853 was one John Stephenson but in 1854 it was Leon Zienkowicz (this is one thing that does not quite tally with the picture I had before because I thought Herzen started the Free Russian Press in a well-established Polish Press at that address)

Anyway, Zienkowicz did move from 38 to 36 by 1855. During the same year the addressee of 82, Judd Street, James Handisyde who is listed as “a printer and stationer”, acquired a new addressee, the inimitably named Adolphus Balls (!) who was a writing master (I am assuming this profession is relevant to our press although I don’t know for sure exactly what it entails – please enlighten me if anyone knows).

James Handisyde continues to be the listed addressee at 82 right up until 1858 when he appears at 2 Judd Street and a watchmaker has moved into No. 82.

James Handisyde continues to live at this address but in 1861 Louis Czerniecki (printer of Russian) appears at 5, Thornhill Place. And very fortunately for the purposes of our investigations, he’s already there in 1862 when the Caledonian Road is extended northwards and subsumes some of the adjacent areas and Czerniecki is listed as being in the same building which is now 136-8 Caledonian Road. He’s still there in 1863 now with the listing “printing office” but there is nothing for 1864.

I couldn’t resist going to have a look and there are 2 terraced houses sporting those numbers which look to me as though they are from the first half of 19th century, so we may even still have the buildings but I will, when I get time, just make sure that the Caledonian Road was not renumbered again before I confirm this.

Richard – I hope this supports the chronology that you and the Marchmont Association are working to – it would be lovely to see that plaque go up round about the time of the anniversary.

Richard Ekins

/ March 29, 2012Many thanks for this valuable work, Sean. I would doubt that Sarah sees these details as affecting our emerging picture of the 82 Judd Street blue plaque case.

sean mitchell

/ April 4, 2012Hi All

Further to my previous post, I’m very pleased to be able to confirm that the 2 houses on the Caledonian Road which I identified as being of an appropriate age to be contemporary with the Free Russian Press are indeed the houses where it was based from 1861-64.

I have managed to track down the plan which was made when the Caledonian Road was renumbered in 1862 and it clearly shows the houses which constituted Thornhill Place in the same configuration as they are today including No. 5 which was renumbered as 136 and 138 Caledonian Road in 1862 and this numbering has been retained on the same houses to this day!

It’s great that we have the original buildings because, as I understand it, our joint research indicates that none of the other original buildings where the press was located survive.

Sean

Sarah Young

/ April 4, 2012Thanks for this, Sean – it’s good to have this confirmation, although my understanding is that this is not the only original building, and that 82 Judd Street is still there, just renumbered.

Anyway, my post is almost complete and will be published on Friday, for the anniversary.

Richard Ekins

/ April 12, 2012Excellent news! I’m glad to report that the Marchmont Association committee have just given the go-ahead to the Herzen/Free Russian Press plaque, subject to permissions and fund-raising.

Any contributions to the fund would be most appreciated – officially through Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association – but anyone is most welcome to email me with initial enquiries.

Richard Ekins

/ December 31, 2012The Marchmont Association now have the necessary permissions to erect the Herzen/Free Russian Press plaque and a mock-up of the plaque has been approved. Considerable funding has been promised already. We are now seeking additional funding. As I said in my previous post, any contributions to the fund would be most appreciated – officially through Ricci de Freitas, Chair of the Marchmont Association – but anyone is most welcome to email me with initial enquiries.

See http://www.marchmontassociation.org.uk/news-article.asp?ID=124

Richard Ekins

/ May 7, 2013As of May 7th 2013, we still have a small way to go before full funding. I would like to thank blue badge guide Sean Mitchell for leading his absolutely excellent inaugural guided walk: ‘Bloomsbury, Herzen and the Revolutionary Tradition’ on Saturday, 4th May. Highlights for me were the fascinating links Sean provided between Jeremy Bentham, Senate House, Unitarianism, Nikolai Chernychevsky, and Lenin. The guided walk ended inside Bevin Court, designed by Berthold Lubetkin. A sheer delight and highly recommended.