Some of the best ideas are destined never to make it into print. They’re usually the ‘wouldn’t it be great if…’ ideas, that you know probably aren’t true, and even if they are, there’s no way you’re ever going to prove them. At the same time you don’t want to let them go altogether. And this is where a blog is good.

While I’ve been thinking and writing about the Crystal Palace recently, and reading and re-reading various things, of particular interest have been two articles by Ekaterina Dianina. The first, ‘Dostoevskii v khrustal’nom dvortse’, Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 57 (2002), 107-25 (‘Dostoevsky in the Crystal Palace’, New Literary Review) claims that Dostoevsky didn’t visit Sydenham during his trip to London in 1862, but instead went to the world exhibition in South Kensington. Some of Dianina’s textual analysis is convincing (although I think her explanation of Dostoevsky visiting the wrong exhibition by error is very weak and unlikely), but in the end I was only persuaded that he conflated the 1862 exhibition with the Crystal Palace, not whether he visited one or the other. But in any case it set me thinking about how one might prove what he did in London.

Dianina’s second article, ‘Passage to Europe: Dostoevsky in the St Petersburg Arcade’, Slavic Review, 62.2 (2003), 237-57, examines the setting of his 1865 satirical story The Crocodile (Russian here) in the St Petersburg arcade, Passazh (The Passage).

The article to a great extent follows the Benjaminian path one would predict, but it also reminds us of the links between such early shopping/entertainment arcades and the design of the Crystal Palace. I have to admit, I don’t think I’d read ‘The Crocodile’ since I was an undergraduate, so I went hurrying back to it. Rediscovering it was a treat. It’s the story of a Ivan Matveich, who visits the Passazh to see the latest curiosity being exhibited there, a crocodile, gets a bit close, and is swallowed whole, but is still alive inside the crocodile, and can talk and take part in discussions about what to do with him, and how it will affect the Russian economy, which then turns into a discussion of political economy — in other words, the man inside the crocodile becomes the new sensation.

As Dianina points out, the crocodile is clearly linked to Europe and progress — it has a German owner, is described as a native inhabitant of Europe, and Ivan Matveich wanted to see it in the first place because he was about to depart on a trip to Europe. And there are also lots of references to the progressive ideas of the day — they are even being discussed in the next room while Ivan Matveich is being swallowed. So there is evidently a connection between the Passazh setting and the satire on contemporary ideas and Western influences.

And then last time I was in Crystal Palace park I went to see Waterhouse Hawkins’s dinosaur models, and I thought…

… wouldn’t it be great if Dostoevsky was thinking of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs when he wrote ‘The Crocodile’. Pretty far-fetched, I’ll admit, but bear with me. The big question (which Dianina’s article doesn’t really address) is: why a crocodile? Is it merely satirizing the fashion for the exotic, or is it a parodic counterpoint to the modernity of the Passazh? Surely the fact that the story involves a prehistoric creature is significant, especially as the story makes direct reference to this:

I hope to live at least a thousand years, if it is true that crocodiles live so long, which, by the way — good thing I thought of it — you had better look up in some natural history to-morrow and tell me, for I may have been mistaken and have mixed it up with some other fossil [ископаемый]. (ch 3)

And as my second picture shows, the Telesoaurs in the park, among the most accurate of Hawkins’s dinosaurs, don’t look that different from crocodiles today. In the mid-nineteenth century, as knowledge of the prehistoric world and understanding of evolutionary theory developed, dinosaurs represented a curious amalgam of the ancient and the contemporary, and as a depiction of the latest knowledge, Hawkins’s models played a very important role in the Crystal Palace’s vision of the present day. This relates to one way I’ve been considering the Crystal Palace recently — its capacity to incorporate or signify opposites simultaneously. But it also makes sense in the context of Dostoevsky’s story; the crocodile, as a form of dinosaur, is both part of the modernity of the Passazh, and its antithesis. When Ivan Matveich, from within the crocodile, starts pronouncing on progressive ideas, the ancient becomes the mouthpiece for the contemporary, just as the Crystal Palace dinosaurs provide a commentary on science and progress by representing the prehistoric world.

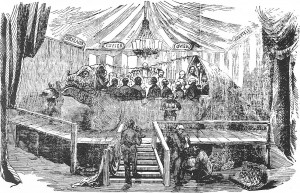

Then there’s the fact that Ivan Matveich is swallowed whole by the crocodile, discovers that its insides are empty and ‘exceedingly roomy’ and, once they have solved the conundrum of how to feed him, is quite happy to stay there. Aficionados of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs will know exactly where I’m heading: the dinner party that Hawkins held in his studio on 31 December 1853 in the body of the iguanodon model.

Is there any evidence that Dostoevsky knew about this event, which has become part of the Crystal Palace legend? Absolutely not, but I’m not going to let that get the in way of a nice idea.

But he almost certainly would have read about the dinosaurs, even if he didn’t see them himself, because they were discussed in the Russian press as part of the phenomenon of the Crystal Palace. This is what Chernyshevsky has to say about them in his 1854 article in Fatherland Notes (Otechestvennye zapiski):

It’s unnecessary to talk say that [the gardens] are full of grottos, waterfalls, fountains, lakes, statues, etc. Let us just say a few words about the collection of antedeluvian animals that are situated in the gardens. These gigantic figures were made life size by Hawkins under the direction of one of the great English geologists and an honourary member of our Academy of Sciences, Owen, from drawings by Cuvier and Mantell, who reconstructed the forms of the monsters of the ancient world from skeletons. The creatures are placed in natural surroundings that reproduce the natural world in which they lived. To give a sense of the terrible size of these monsters we can say that many of the models weight more than 2,000 puds [1 pud = 36 pounds] and the body of the iguanadon is supported by the iron pillars 4 arshins thick [1 arshin = 28 inches] that constitute the bones of its four legs. And there are many monsters whose size outdoes that of the iguanadon. In the Sydenham park there stand an icthyosaurus — a fish-like lizard which combines the form of reptile, bird, mammal and fish — a labyrinthodon, a mastodon, dozens of other antedeluvian giants and the biggest of all their contemporaries — the megalosaurus, before which an elephant today would be like a sheep before a crocodile. (Section 7, pp. 94-5)

… and there’s our crocodile. Dostoevsky was not long out of prison when this was published, and, having been isolated from literary life for so long, was devouring every journal he could get his hands on. Fatherland Notes was one of the most important literary journals at that time, so it’s likely to have been pretty high up Dostoevsky’s reading list.

So, in 1854, the rising star of the new radical generation describes the dinosaurs and compares one to a crocodile. A decade later Dostoevsky, in the middle of his dispute with the nihilsts, in which the meaning of the Crystal Palace is of huge symbolic importance, writes a story that features a crocodile in an arcade spouting radical ideas. Coincidence? I’d like to think not.

2 Comments