Reading: Dostoevsky, “Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (1877)

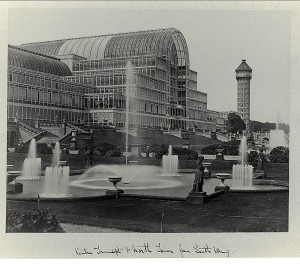

So we come to the end of this lecture series, and a slightly different focus than previously, as theoretical works take a back seat, and we look instead at Russian literature and culture to explore the utopian theme. There are clearly strong utopian aspects to the work of several of the thinkers we have examined so far, not least in the writings of Vladimir Solov’ev and Nikolai Fedorov that we have studied over the last month, and these did have a significant influence on other writers and thinkers. But it is in literature itself that the utopian theme really comes alive. I’ve already mentioned in previous lectures the utopian dream of the Crystal Palace that features in Chernyshevsky’s novel What is to be Done? (1863), and the response of Dostoevsky’s underground man, and both works indicate the place of literature in the debate about utopianism. Today I want to flesh that question out more, by placing those two works in the larger context of utopian (and dystopian) Russian fiction and cultural reference, and as part of that also to introduce some aspects of Dostoevsky’s “Dream of a Ridiculous Man,” which is the set reading for our final seminar. The reason I’ve chosen that text, out of the many utopian visions on offer, is that it brings together the three key themes for the course, the person, love and utopia, but also I think it’s quite an ambiguous text, which can be seen as both utopian and dystopian, and therefore has the potential to reveal important aspects of this whole theme.

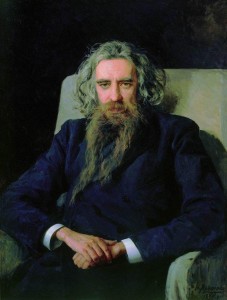

I suggested in my last lecture that the utopianism of Russian thinkers was related to the question of communality; particularly in the radical form Fedorov’s utopia takes, the idea of brotherhood or kinship is so significant that it logically leads to the task of resurrecting the dead. So this already implies the connection between utopianism and love, and because that privileges other people above the self, it entails a particular conception of the person that we might see as being common to Russian thought. Another reason for the popularity of utopianism in Russia is probably the simple notion of faith in a brighter future, so that the present is not perceived in terms of the deferred happiness of the current generation for the sake of what is to come (something that, for example, Herzen repudiates, which indicates his anti-utopian position). Rather, the brighter future becomes an explanation for the torments and trials of the present, and I think the idea that the present is full of suffering, and that the Russian people have suffered greatly for a very long time, is quite a tenacious one within popular perception. The notion that Russia is precisely the place where this future transformation must happen often originates in emphasis on Russian backwardness, but one might also suggest there is an element of belief that Russia is most in need of this transformation, and its long-suffering people are most deserving of this paradise to come. I use terms like “belief,” “faith” and “paradise” deliberately, because I think there is an intrinsically religious dimension to this question, whether it is expressed in its Christian or its revolutionary form. The role of the latter in the communist experiment is another important question.

A utopia strictly speaking is the image of a perfect society, not an argument about society, which is why the literary dimension becomes so crucial (Fedorov stated: “the representation of the world will then become a project for a better world,” p. 29). But I want to start not by examining not a literary work, but by looking at a couple of utopian elements in Russian history. Leonid Heller and Michel Niqueux’s book on Russian utopianism identifies so many aspects of Russian history as utopian (from the colonization of Siberia to the Pugachev rebellion to the Decembrist uprising) that the term threatens to become meaningless. But some of their analysis is thought-provoking, and, for example, the idea of Peter the Great – and his creation, St. Petersburg – as utopian (Heller & Niqueux, pp. 61-2) has a lot of potential. One could relate this not only to the underground man’s characterization of Petersburg as “the most abstract and premeditated city in the whole world” (Notes from Underground [1864], p. 5), which emphasizes its rational origins, but also Dostoevsky’s more ambivalent and irrational image of the city rising up with the mist to disappear in the 1848 short story “A Weak Heart” and, here, in the novel A Raw Youth (1875):

I consider St. Petersburg mornings, apparently the most prosaic on earth, probably the most fantastic in the world. […] On such a St. Petersburg morning – so raw, damp and foggy – I have always thought that the wild dreams of someone like Pushkin’s Hermann in The Queen of Spades […] must be strengthened and receive endorsement. A hundred times over amid such a fog I have had the strange but persistent notion: ‘What if this fog were to disperse and rise up into the sky, wouldn’t the whole, rotten, sleazy city go up with it and vanish like smoke, and all that would remain would be the original Finnish marsh with, in the middle of it, for decoration, perhaps, a bronze horseman on a snorting, rearing steed?’ […] I’ve frequently been struck – and am still struck – by a completely senseless question: ‘Here they are, you see, all rushing and hurrying on their way, but what if this were perhaps someone’s dream, and there wasn’t a single, true, genuine human being, not a single real action among them? If the person dreaming it all were to wake up, it would all suddenly vanish. (An Accidental Family [A Raw Youth], p. 144)

This image of Petersburg rising from the Neva that Dostoevsky evokes more than once in his work may also have its origins (albeit with the sense reversed) in a story from popular Russian culture that represents one of the best known religious expressions of utopianism: the mythical city of Kitezh, which resisted the Mongol invasion by lowering itself into Lake Svetloyar, near Nizhnyi Novgorod, where it remains submerged, only visible to the pure in heart (the question of the seen and unseen may be a very significant aspect of the subject of Russian utopias; it reappears below in a rather different context). Kitezh is important not only because of its persistence in Russian folk memory (resulting in numerous art works and Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1907 opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniia), but also because of its specifically religious dimension, which works in two ways. Kitezh represents a form of peaceful non-resistance to violence that we can relate to Tolstoi’s ideas, and which goes back to the 11th-century martyrdom of Saints Boris and Gleb, the first Russian canonized saints.

But it also plays a significant role in Russian religious history, because although the legend relates to events in the 13th century, it first appears in an 18th-century Old Believer chronicle. The Christian concept of the Kingdom of God on earth – in itself utopian – takes on a more concretely Russian dimension in the idea of Moscow as the Third Rome (Heller & Niqueux, pp. 23-4), but the schism in the Orthodox church in the 1660s entrenches utopian thinking, because the Old Believers and sectarians see the true faith as lying outside the established church, and therefore reject both church and state to seek salvation beyond this world, or attempt to realize ideal apostolic communities on earth (Heller & Niqueux, p. 33). One significant example of this idea in practice was the Vygorskaia pustyn’ Old Believers’ community in Karelia, founded in 1694, which has been seen as a realization of Charles Fourier’s idea of the phalanstery (Heller & Niqueux, pp. 34-5), the self-contained utopian working together for the mutual benefit of all (of which a little more later).

Turning to fictional Russian utopias, probably the first true representative of this theme in Russian literature, following the translation of More’s Utopia into Russian in 1789, is Untrue Un-Events, or A Voyage to the Centre of the Earth (1824), by the Faddei Bulgarin (1789-1859), the conservative writer and self-appointed champion of the autocracy, best known for editing the reactionary journal The Northern Bee. Bulgarin’s reputation for being one of the most unpleasant figures in Russian literature (a title for which there is quite a lot of competition) and his somewhat dubious merits as a writer make this a rather depressing inauguration of the utopian theme – and indeed as an early contribution to the genre of science fiction in Russian literature. His image of three underground lands satirizes the backward peasantry (the “land of Ignorance”) and the middle-classes who pretend to knowledge they do not have (the “land of Beastliness”), and in contrast exults in the self-disciplined subordination to authority of,

the smug, patriarchal country of Enlightedness [that] is an autocratic emasculation of More, silent on his basic insights about property and economics, and propagating an idealized stance popular at the Tsarist court from the times of Peter the Great. (Suvin, p. 140)

Of distinctly greater appeal and literary interest is the work of Vladimir Odoevsky (1803-1869), a writer and thinker associated in the 1820s with the Liubomudry (society of Wisdom Lovers), a discussion group devoted to German philosophy (above all the works of Schelling) to which both future Slavophiles and Westernizers belonged. Odoevsky’s unfinished novel The Year 4338 – set in the Petersburg of the future – contains elements of Cosmist thinking such as space exploration to exploit the resources of other planets (so in this sense Odoevsky was a precursor of Fedorov) and other futuristic ideas such as the machine authorship of novels (Suvin, p. 141). While this work belongs more firmly to science fiction, and was one of a number of Russian works at the time depicting the distant future, of more interest to us is another of his stories, from the collection Russian Nights (1844). It is often assumed that Chernyshevsky first introduced into Russian literature a utopia based on a specific ideology (rational egoism), in What is to be Done?, but in fact Odoevsky’s “A City without Name” predates this by over 20 years (it was first published in 1839). Moreover, the earlier story is based on the same philosophical foundations: Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism (Artem’eva’s article makes this connection but does not explore it). But this is already not a utopia but a dystopia: Odoevsky narrator – a stranger surveying the ruins of his fatherland – describes the catastrophic results of the adoption of the theory that “benefit is the essential motive power of all man’s actions! Whatever is useless is harmful, whatever is of benefit is permitted” (Odoevsky, pp. 103-4). Bentham is named as the inspiration for a new society constructed in a new place (although it is neither named nor located, one could probably make an argument that it contains allusions to Petersburg’s rational, constructed character). But gradually this society begins to go wrong. There are disputes about what (or whose) benefit is in question, but eventually it is the fact that benefit is understood solely in terms of financial interest and as only applicable to the Benthamite society that leads to disaster, as the benefit of the “city without name” overrides all others leading to exploitation, war and colonization of its neighbours, and followed by inequality and lack of cooperation at home, which also leads to bloodshed and a dog-eat-dog mentality:

One thing alone was considered necessary – to obtain a few material benefits for oneself by hook or by crook. […] Mothers knew no songs they could sing at their babies’ cradles. The natural, poetic element was long since killed by selfish calculations of profit. The death of this element contaminated all other elements of human nature; all abstract, general thoughts which unite people seemed to be madness; books, knowledge, laws of morality – useless luxury. Only one word – benefit – had remained from former glorious times, but it, too, acquired an indefinite meaning; everyone interpreted it in his own way. (Odoevsky, p. 109)

Eventually the society regresses to savagery and the city is destroyed, its people dying of starvation. It gives a very bleak picture that questions the human capacity for good and presents a strong indictment of the subordination of society to an idea (we might compare this to Herzen’s rejection of abstract principles and institutions only a few years later). And it represents quite a sophisticated view in comparison with Chernyshevsky’s blithely optimistic vision of the Benthamite future in Vera Pavlovna’s dream in What is to be Done?, in which there are no tensions, and everybody living in the Crystal Palace is happily working together in the secure knowledge that they are acting in their own best interests and everybody else’s. Inspired by Fourier’s Phalanstery, a design for collective cooperative living and working in an “balanced harmony of personal and public life” (Suvin, p. 143), and representing one of the earliest literary works to depict Fourier’s idea in practice, Chernyshevsky’s socialist utopia presents a strong, and perhaps facile, contrast to Odoevsky’s capitalist nightmare.

Whatever its merits (or otherwise), Vera Pavlovna’s dream has significant dimensions – in particular, as we saw last term, in the idea of gender equality and the assumption that there can be no social progress or liberation without equality for women, and in establishing Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace as the primary image of the future utopia. The emphasis on liberty is central to Chernyshevsky’s idea, but for Dostoevsky, such attempts at social reorganization, however well intentioned they may be in their initial inception, always entail unfreedom, because of the loss of individuality. Freedom, as we will remember from Notes from Underground, is the ultimate value, because it is a prerequisite for the maintenance of the individual personality. I do not intend to revisit the arguments in that text in any more detail, but I do want to mention later incarnations of Dostoevsky’s “anthill” theory of social slavery, as he called it, in which again the question of freedom becomes central. In Demons (1872), the revolutionary Shigalev outlines a theory of social reorganization that explicitly leads to slavery:

He proposes, as a final solution of the question [of social organization], the division of mankind into two unequal parts. One-tenth is to receive personal freedom and unlimited rights over the remaining nine-tenths. The latter are to lose their individuality and turn into something like cattle, and with this unlimited obedience attain, through a series of regenerations, a primordial innocence, something like the primordial paradise, although they will have to work. (Dostoevsky, Demons, p. 447)

Beyond this rather ominous final line, one can see here the connection with Raskolnikov’s idea in Crime and Punishment (1866) of the division of people into the extraordinary one-tenth, to whom the law does not apply, and the ordinary nine tenths, who must obey the law. Also significant here is the idea of a return to the original paradise; we will need to think about how these consequences of social reorganization affect our view of the perfect world depicted in “Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (of which more below).

In his final novel The Brothers Karamazov (1880), Ivan Karamazov tells his brother Alesha about his “poem,” the story of the Grand Inquisitor, who confronts the returned Christ to argue that freedom is too heavy a burden for human beings to bear:

You want to go into the world, and you are going empty-handed, with some promise of freedom, which they in their simplicity and innate lawlessness cannot even comprehend, which they dread and fear – for nothing has ever been more insufferable for man and for human society than freedom! (Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, p. 252)

Out of love for suffering and weak humankind, he has replaced the Christian precepts of faith, love and free will with “miracle, mystery and authority,” giving his flock bread and certainty (Brothers Karamazov, p. 255). Thus he restores humanity’s happiness, by removing the burden of freedom for the majority:

Yes, we will make them work, but in the hours free from labor we will arrange their lives like a children’s game [note again the question of innocence here – SJY], with children’s songs, choruses and innocent dancing. Oh, we will allow them to sin, too; they are weak and powerless, and they will love us like children for allowing them to sin. […] And everyone will be happy, all the millions of creatures, except for the hundred thousand of those who govern them. For only we, we who keep the mystery, only we shall be unhappy. (Brothers Karamazov, p. 259)

It represents possibly the greatest literary expression of the tension between freedom and happiness, and it is important because although this is certainly a dystopian view – a warning against attempts to reorganize society on rational grounds (for the Grand Inquisitor has certainly adopted the rational perspective) – it does not in any way deny the significance or validity of the Grand Inquisitor’s argument: freedom is difficult, certainty is comforting; and in many circumstances human beings may be prepared to sacrifice the former for the latter.

We see a similar opposition between freedom and happiness presented, with perhaps just as little resolution, in Evgeny Zamyatin’s novel We (1921), which like Dostoevsky’s works is often seen as a prophetic anticipation of the totalitarian stalinist state. Probably the most fully developed image in Russian literature of the rationally constructed society where all individuality is eradicated for the sake of the collective, the novel is often viewed purely as a dystopia, but I would argue that it is slightly more ambivalent than that suggests, because of this question of happiness. As the story opens D-503 accepts the rational society and his insignificant place within it, but as he grows a “soul” and experiences new emotions (and becomes an artist through the writing of his journal), this is clearly not a route to happiness or contentment – quite the opposite. He never commits totally to this new side of life or to freedom; whatever the excitement he experiences, he remains fearful and misses his former certainty. When he is subjected to the operation to remove his imagination, we recognize horrific significance of this, but at the same time we cannot deny that the restoration of certainty also corresponds to something he craves.

Zamiatin’s novel We is also important for containing another incarnation of the Crystal Palace, in the form of the glass construction of OneState, where everything is “clear” (ясно, D-503’s positive watch-word). The transparent city that removes all concept of privacy and allows its inhabitants’ every activity to be seen, moreover, recalls not only the Crystal Palace, but also another building: Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, the institutional building (usually associated with prisons and asylums, but also designed with schools, hospitals and workplaces in mind) that enables total surveillance through a central inspection point, while the inmates would never know whether they were being watched or not (so the question of certainty is turned on its head here). The panopticon becomes, most famously in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (p. 205), an instrument of power, although Bentham himself also perceived it in these terms. Incidentally, Jeremy Bentham’s began writing his famous essay on the panopticon in 1786 whilst visiting his brother Samuel, who was living in Russia and working on a number of projects with Prince Grigory Potemkin. The initial idea for the panopticon or inspection house was, in fact, Samuel’s, and the first (perhaps only true) panopticon was built as a school of the arts in St. Petersburg in 1806, on the banks of the river Okhta on the Vyborg side (Werrett, p. 21); it was burned down in 1817 (see ; Steadman, pp. 5-9, for further details of the building, including plans). So from the earlier Muscovite utopia of the Third Rome, the focus seems to shift, and by the beginning of the nineteenth century, utopian (or dystopian, depending on your perspective) Petersburg seems to be where all these ideas come together.

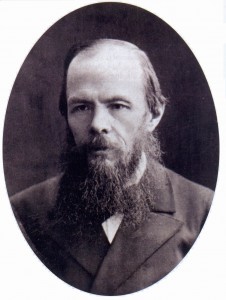

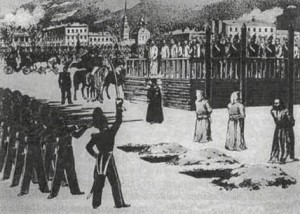

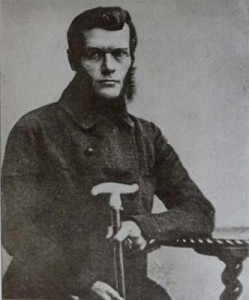

And St. Petersburg is also the setting for Dostoevsky’s “Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (at least for the action that frames the central dream of the title), a short story published in April 1877 as part of his Writer’s Diary. This was a writing experiment Dostoevsky conducted intermittently in the 1870s, publishing a “fat journal” (Grazhdanin, The Citizen) in which, instead of containing contributions from lots of different writers, he wrote everything himself. It is a strange hotchpotch of different forms of writing, on different subjects, and is very interesting as a source of information on Russian urban and intellectual life, as many of the articles relate to contemporary events. For example, there are articles on court cases and the judicial system, on children who were the victims of violence, and on the position of women (often part of his interest in court cases). There are a large number of articles on the “Russian question” (i.e. on the destiny of Russia) which often incorporated religious questions and praise for the Orthodox church, while in 1877 there is a great deal on the Russo-Turkish war in the Balkans. This is where Dostoevsky’s nationalism and anti-Semitism come most clearly into view, revealing the most unpleasant side of his personality and ideas, but these articles are also notable for the absence of the subtlety and complexity that marks the representation of ideas in his fiction. The Writer’s Diary also contains several short stories in which death and the possibility of life after death are significant preoccupations, including “Dream of a Ridiculous Man.”

This story of a morally indifferent rationalist whose life has lost all meaning, who dreams of committing suicide and is transported in the afterlife to an earthly paradise. The paradise he visits is the fullest development of a recurring image Dostoevsky calls the “Golden Age,” inspired by the painting “Acis and Galatea” by Claude Lorrain (c. 1600-1682). In Demons and A Raw Youth, the central characters, Stavrogin and Versilov respectively, glimpse this ideal in a dream:

It was this picture I dreamed about, though not as a picture but as if it were a kind of myth. […] It was a reminder of the cradle of European humanity, and that very idea filled my heart with a loving fellow feeling. Here was humanity’s paradise on earth, the place where gods would come down from heaven and become as one with men… […] I remember that I was elated. A sensation of happiness such as I had never known filled my heart till it ached. It was a love for all humanity. (An Accidental Family [A Raw Youth], pp. 491-2)

But in both cases the ideal is immediately negated by man’s imperfections – indeed by the very imperfections of those dreaming about it (Peace, p. 62). But in “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man,” the paradise is not simply passively glimpsed; the dreamer participates in the life of its inhabitants, and has an effect on them. Peace argues that the idyll depicted in the story represents a further answer by Dostoevsky to Chernyshevsky’s utopian vision of the Crystal Palace. Certainly Dostoevsky’s story contains formal echoes of his adversary’s utopia. Both “perfect societies” appear in dreams, and, like the Ridiculous Man, Vera Pavlovna is guided through time and space to reach this world by a supernatural being. But the basis of the two utopias is very different:

[Dostoevsky’s] Utopia is based not on the progress of human reason, but on the retention of innocent primal feelings; for him the Golden Age is not in the future but in the past, and its image derives not from a construction of science but from a work of art. (Peace, p. 73)

The shift from future to past, and from reason to pre-rational knowledge, is accompanied by a transformation in the significance of love: while erotic love is central to the sexual equality envisaged in the Crystal Palace, innocent brotherly love governs Dostoevsky’s “Golden Age.”

But I would suggest that far more important than the structure of this society in comparison with the Crystal Palace, is the fact that it is corrupted by the Ridiculous Man. This not only emphasizes the impossibility of this type of perfect society, but also apparently supports the underground man’s assertion that people are more interested in the journey than its goal, and that the destructive urge originates in humanity’s dislike of perfection; the narrator portrays his actions that led to this fall as accidental, but when we compare this story to Notes from Underground, the suggestion must be that this action was on some level deliberate, the result of an unconscious impulse to destroy.

But is the society depicted in the story – prior to its fall – perfect at all? Some critics agree that it is, but one might also argue that it cannot be perfect because of the incomplete nature of the people who inhabit it, while the reduction of human beings to an innocent child-like state in the dystopias Dostoevsky depicts elsewhere should also give us pause for thought. This will be one important question for us to discuss next week. You should also consider how this society is corrupted, the significance of suffering, and where (if anywhere) religion fits into Dostoevsky’s conception. We shall also discuss what the story and its central dream suggest about human nature and the individual.

Sources

Artem’eva, T. V., “Stekliannyi dom”, in Filosofskii vek. Al’manak, No. 9: Nauka o morali: Dzh. Bentam i Rossiia (St Petersburg, 1999), 135-52

Bulgarin, Faddei, “Neveroiatnye nebylitsy ili Puteshestvie k sredotchiiu Zemli” (Untrue Un-Events, or a Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 1824)

Chernyshevsky, Nikolai, What is to be Done?, trans. Michael Katz (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989) | Chto delat?

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (London: Vintage, 1992) | Bratia Karamazovy, chast’ 1 | chast’ 2 | chast’ 3 | chast’ 4

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, “Dream of a Ridiculous Man,” in A Writer’s Diary, trans. K. Lantz (London: Quartet, 1994), 943-961 | Son smeshnogo cheloveka

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, An Accidental Family [A Raw Youth], trans. Richard Freeborn (Oxford University Press, 1994) | Podrostok

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, Demons, trans. Robert A. Maguire (London: Penguin, 2008) | Besy

Dostoevsky, Fyodor, Notes from Underground, trans. Michael Katz (New York: Norton, 2001) (2nd edn) | Zapiski iz podpol’ia

Fedorov, Nikolai, “The Question of Brotherhood or Relatedness,” in Russian Philosophy, ed. J. M. Edie, J.P. Scanlan and M.B. Zeldin (Chicago, 1965), 3: 16-54

Foucault, Michel, Discipline and Punish (London: Penguin, 1991)

Heller, Leonid, and Niqueux, Michel, Histoire de l’utopie en Russie (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1995)

Odoevsky, Vladimir, “A City without Name,” in Russian Nights, trans. Olga Koshansky-Olienikov and Ralph Matlaw (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1997), 101-14 | Gorod bez imeni

Odoevskii, Vladimir, The Year 4338, trans. John Kuti | 4338-ii god (1835)

Peace, Richard, “Dostoevsky and the Golden Age,” Dostoevsky Studies, 3 (1982), 61-78

Steadman, Philip, “Samuel Bentham’s Panopticon,” Journal of Bentham Studies, 14 (2012)

Suvin, D., “The Utopian Tradition of Russian Science Fiction,” Modern Language Review, 66.1 (1971), 139-59

Werrett, Simon, “Potemkin and the Panopticon: Samuel Bentham and the Architecture of Absolutism in Eighteenth Century Russia,” Journal of Bentham Studies, 2 (1999)

Zamyatin, Evgeny, We, trans. Clarence Brown (London: Penguin, 1993)

For links to translations of Dostoevsky’s works, click here.