“The dead are people too.” Andrei Platonov, The Foundation Pit

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the influence on nineteenth-century Russian literature of romantic and gothic sensibilities, and of fantastic writers from ETA Hoffmann to Edgar Allan Poe, the notion of the undead plays a significant role for some of the most prominent Russian writers. Encompassing not only supernatural entities but also out of body experiences (and dreams of these) and other, less fantastic, conceptions of a living death or return from the dead, the theme plays a central role in Russian culture. Apologies for any plot-spoilers, though generally the plot as such is barely the point. Where possible I’ve included links to Russian texts, with the translations of the featured texts that are available online given at the end of the entry.

10. Lev Tolstoy, The Living Corpse (1900) I’m no great fan of Tolstoy’s plays, as the ones I’ve read seem to have a clunkiness he avoids even in his most didactic fiction. The Living Corpse is fairly typical in that respect, but it is interesting in other terms. Not literally a story of the undead, this drama about a debauched man who fakes his suicide to free his wife belongs to the meme of fake deaths in Russian literature, which frequently seem to occur in order to resolve love complications: see also Sukhovo-Kobylin’s Tarelkin’s Death and Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done? Tolstoy’s play can be seen as a response to the consequence-free fake suicide of Lopakhin in Chernyshevsky’s novel, but it also acts as a commentary on Anna Karenina and questions of love, adultery and divorce.

9. Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (1928-40, published 1967) Satan’s ball, in which murderers and criminals from across the centuries come back to life, is so exuberantly described it is easy to overlook the horrific side of this scene. It is above all aimed at testing Margarita, and considering the grim physical and emotional ordeal she goes through, one has to question whether the reunion it ultimately achieves is worth it. The Master is so badly damaged that his return – another form of resurrection – cannot restore the past. There is no happy ending here. Bulgakov’s preoccupation with the dead is also apparent in is early feuilleton “Adventures of a Dead Man” and in the subtitle to his Theatrical Novel: Notes of a Dead Man.

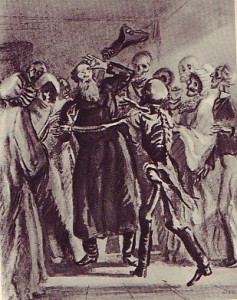

8. Alexander Pushkin, The Undertaker (1830) The Tales of Belkin are extraordinary creations, but The Undertaker usually gets much less attention than The Shot, The Stationmaster or The Snowstorm. It probably isn’t quite as perfectly formed as some of the other tales, but its climactic image of the corpses he has interred turning up to Adrian Prokhorov’s housewarming is a wonderful excursion into the fantastic that adds another layer to Pushkin’s parodies and creates a connection with The Queen of Spades. It also alerts us to how frequently the appearance of the undead is related to alcohol in Russian literature (see also Odoevsky’s The Tale of a Dead Body, Belonging to No-One Knows Whom, and Zoshchenko’s vignette The Living Corpse).

7. Yuri Dombrovsky, The Keeper of Antiquities (1964) My former PhD student Katia (now Dr) Shulga had some brilliant insights into the uncanny imagery of dead brides in Dombrovsky’s dilogy The Keeper of Antiquities and The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, but one related reference stays particularly in my mind because of the coincidence of its discovery. Katia was wondering about an obscure reference to Marusya being shot in the civil war and then returning from the dead, when I published a blog post about the anarchist atamansha, Maria Nikiforovna, who was famous for the legends surrounding her death and multiple returns. The inclusion of Marusya – a startling example of the diversity of Dombrovsky’s knowledge – gives an unsettling additional dimension to the theme of dead beauty haunting the living.

6. Daniil Kharms, The Old Woman (1939) There’s an enormous amount of death in Kharms, so it’s not surprising that a little undead-ness creeps in as well. The old woman who inexplicably visits the narrator’s room, only to die, proves very troublesome. When the corpse starts crawling across the floor the story enters a different realm altogether. Or does it? Does this actually signify that she’s not dead at all? The narrator hasn’t checked that carefully, after all, and given his inability to tell a simple story, he hardly seems qualified to understand or report coherently on this aspect of the incident. In which case, does it become murder when he kicks the “corpse”? If so, it makes one rethink a great deal of the story, particularly the religious theme and the closing prayer. | English translation

5. Nikolai Gogol, Viy (1835) From the metaphorical return of the “dead souls” in Gogol’s novel, to the muscular “ghost” of Akaky Akakievich who vengefully steals overcoats from passers by, the undead are a constant presence in Gogol’s work. For me the most memorable occurrence comes in the Mirgorod story Viy, when the philosopher Khoma Brut spends three nights in a church under attack by the beautiful witch he killed, each night more horrifying than the last, and culminating in the appearance of multiple demons and the eponymous monster the Viy, with his all-seeing eyes and iron face. The second cock crow leaves all the demons frozen inside the church, and the image of it abandoned and overgrown with weeds is for me the perfect expression of the clash of pagan and Christian cultures at the heart of Gogol’s Ukrainian stories. | English translation

4. Vladimir Odoevsky, The Live Corpse (1838, published 1844) When Vasily Kuzmich dies, his spirit goes wandering, and discovers that those who ostensibly mourn his passing in fact haven’t got a good word to say about him. As his moral decay and obsession with money in life become ever clearer, he gradually begins to understand that he is in a form of purgatory because he can no longer affect anything, but must merely witness the consequences of his previous greed and corruption, as his sons take his philosophy to its logical conclusion. A remarkably down-to-earth tale of life after death, and not just because of the fairly standard demystifying ending.

3. Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, The Thirteenth Category of Reason (1927) Krzhizhanovsky’s capacity for genius scenarios never ceases to amaze me, and I love this story of a sociable, philosophical corpse who gets so carried away chatting to a gravedigger that he literalizes his ‘lateness’ by missing his own funeral. One chance at being buried is all you get, it seems, and this turns into a more tragic tale of dislocation as the living are unwilling to accept him and the inhuman bureaucracy cannot accommodate him.

2. Dostoevsky, Bobok (1873) For Dostoevsky, the question of death, and life after death, are persistent preoccupations, in terms of how they are experienced and depicted as well as in their philosophical significance. Most of the stories from Diary of a Writer deal with death and the afterlife in one way or another, but Bobok is definitely my favourite despite (or perhaps because of) the much darker picture it paints than The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, with which it is often paired. As the corpses in their graves play cards, abandon all shame, and have no conception of the meaning of their situation, the banality of the afterlife here seems even worse than Svidrigailov’s conception in Crime and Punishment of life after death as a filthy bath house full of spiders. One of my students recently suggested a connection with The Crocodile, in the image of these prone, constricted figures carrying on as though nothing has happened, which certainly gives food for thought. | English translation

1. Intergalactic zombie agriculture! or Nikolai Fedorov’s Philosophy of the Common Task (1906, 1913; published posthumously) I know it’s not literature per se, but Fedorov has to take first place not only because of the sheer brilliance of his idea of reassembling and reanimating the dead, and populating other planets with the resurrected, which influenced the development of rocket science (after my class on Fedorov a couple of weeks ago a student said she was really envious of his imagination, and I feel the same), but also because he epitomizes the extraordinary significance of resurrection in Russian culture, which I hope this list also indicates. For more on his ideas, see my lecture, and some other links, including to the Russian and English texts.

2 Comments