Readings: Solov’ev, “The Meaning of Love”

Vladimir Solov’ev (1853-1900) is a very significant figure in the history of Russian thought as well as being a very prominent poet, but in terms of his ideas, he is also a very challenging figure, whose work many people find difficult to understand.The text on which we are going to focus in next week’s seminar, “The Meaning of Love,” is a good deal more accessible than many of his other philosophical works, but it may give a somewhat limited impression of him, or even worse, suggest that he is significant primarily for getting involved in an argument with Tolstoy about the merits, or otherwise, of sex. That is certainly not the case, but I think in order to understand why “The Meaning of Love” is so important, it is necessary to know something about the background to his thinking, and to introduce some of his fundamental ideas. So for this lecture I’m going to start off with a few words about why he was so significant, give a biographical sketch, and then look at some of the ideas we see in his work generally.

Solov’ev was a religious philosopher, who is largely credited with inspiring the turn towards religious and spiritual ideas by many members of the Russian intelligentsia at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. This took place parallel to the development of revolutionary ideologies in Russia, and Solov’ev effectively set out the questions and terms of the debate that became central to the concerns of this next generation of thinkers, which included people like Nikolai Berdiaev, author of The Russian Idea, who became the most famous representative of popular émigré Russian thought after the revolution.

Solov’ev’s influence was so great, I think, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, he was, unlike the writers we have studied so far in this course, a professional philosopher, and he was therefore, in theory at least, more rigorous in his methods than many of his predecessors. The fact that he was using more rigorous methods to explore religious ideas (examining both spiritual and institutional questions) showed this group of younger philosophers that there were alternatives to the socialist/atheist models they had been working with. However, one might also question just how rigorous Solov’ev really was – there is also a mystical side to his work, and certainly at times he seems to use the same terms in different ways without properly defining them.

But these caveats perhaps also relate to the second reason for his significance, which is the fact that he was a poet, who was very influential in the foundation of the symbolist movement (most closely associated with the writers Aleksandr Blok and Andrei Belyi) that emphasized mystical and spiritual ideas. So he had a profound involvement in Russian culture that cemented his position. Furthermore, Solov’ev’s friendship with Dostoevsky, which began in 1877, was very important, and in particular we see the influence of some of his ideas on Dostoevsky’s final novel The Brothers Karamazov, in which he has been identified as the inspiration for both Alesha and Ivan Karamazov. Thus Solov’ev’s philosophy reached a wider audience than otherwise might have been expected. He also played a role in popularizing the ideas of others through his lectures. In particular, as we shall see in the next lecture, he was influenced by the thinking of Nikolai Fedorov, whose ideas about resurrection and bodily transformation we shall be examining in the next lecture.

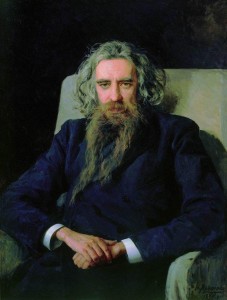

So who was Vladimir Solov’ev? Born in 1853, he was the son of the famous historian Sergei Solov’ev (1820-1879), who was a professor of history at Moscow University and renowned for his monumental History of Russia. Vladimir Solov’ev’s grandfather was an Orthodox priest, and he was brought up in the Orthodox faith. In his early teens he embraced atheism and became interested in the radical ideas of the day — this is the mid-1860s, so we’re talking about nihilist/populist/socialist ideas — but this was only a brief phase, and by the age of 18 he had returned to the Christian faith. His faith was rather mystically inclined, but on the other hand he maintained a concern with social questions, and was interested in ideas about the transformation of society and the regeneration of humankind.

From 1869 to 1873 he studied natural sciences, and then history and philology at Moscow University. He was very widely read in European philosophy, and after his graduation from university, in quite an unusual move, he spent a year at the theological academy at Sergiev Posad near Moscow, the spiritual centre of the Russian Orthodox church. So he also became very knowledgeable about theological and mystical literature. After this he began teaching at Moscow University. In 1875 Solov’ev came to London to work in the British Library, to do research on Cabalistic and mystical literature. (You can read more about this episode in Solov’ev’s life here.) While he was working in the reading room, he had the second of three visions of the personification of divine wisdom, which he called “Sophia” – the first had occurred during a church service when he was nine years old. But this second vision in the British Library was also a voice, telling him he had to go to Egypt, where he would be granted a fuller vision. So he immediately packed his bags and set off for Egypt. There, still wearing the heavy hat and coat he had struggled to get used to in London, he was robbed by the Bedouin in the desert (Mochul’skii, p. 69), but he did have a further vision. He described this as a vision of universal harmony and the simultaneous experience of past, present and future, which he saw as affirmation of his faith. (He wrote a poem about these visions called “Tri svidaniia,” translated by Ivan M. Granger as or “Three meetings”.)

After his vision, Solov’ev returned to Russia. He spent the years 1877 to 1881 lecturing, including his famous series of twelve “Lectures on Godmanhood,” which established his reputation. This was where he first met Dostoevsky (Tolstoy also attended some of these). He resigned from the university in 1881 following the assassination of Alexander II; he had called upon the new tsar to show Christian love and mercy, and not execute the revolutionaries from Narodnaia volia who had committed the crime. His view was widely misinterpreted, and he was accused of supporting tsaricide, which left him in an untenable position. From then on concentrated on his writing alone, and in later life became increasingly pessimistic and somewhat apocalyptic. Towards the end of his life (he died at 47), views varied on whether he was simply getting more and more eccentric, or was in fact insane. He certainly cultivated an extraordinary self-image, and I do not think it is by accident that he looked increasingly like an Old Testament prophet.

When it comes to his visions and the more enigmatic aspects of his thinking, some people find Solov’ev a bit hard to take (though his ideas at fist glance are less eccentric than those of Fedorov). It is certainly not easy for everyone to reconcile this spiritual side of his experience with the claims that he is a more rigorous type of philosopher than we are used to seeing on this course. But it it is important to understand that he was attempting to marry philosophy and faith, and was driven, following his visions, by a “desire to transcend the fundamental opposition of intuition and intellect” (Kornblatt annd Gustafson, p. 10).

Although the mystical side was very important to him personally – and it did inform some of his most important ideas – he was trying to get away from the idea of blind faith, and move towards a more informed faith and insight into divine truth. He saw this as only possible through questioning received ideas and using philosophical inquiry to arrive at a conscious faith. So ultimately he viewed philosophy as bridge between scientific fact and revealed or divine truth; philosophy for him becomes a means by which the person becomes an individual thinking self. Nevertheless, he is a very challenging writer, and many people find him very difficult. I find that when I’m reading it, adopting the sort of mind-frame I have when I’m reading poetry helps to make sense of it, although that may raise questions about just how rigorous and philosophical he therefore is.

Because he is quite problematic, I want to focus first on outlining in as straightforward terms as I can some of the fundamental categories that underlie the particular questions we will be examining in “The Meaning of Love,” so that we can look in more detail at the ideas in that text in the seminar.

We have seen that the idea of unity is central to the work of a lot of different Russian thinkers, and certainly, this question is fundamental to Solov’ev philosophy. The Russian term he uses is vsetsel’nost’, and this is usually translated as “wholeness,” “integrality” or “total-unity.” Sutton – probably the clearest critic on Solov’ev’s main ideas – describes it as Solov’ev’s “requirement that man should use all his faculties in his service of the truth” (p. 16). For Solov’ev this has implications for everything from ethics to universal institutions. On the latter question, the striving for unity saw Solov’ev espouse the reunion of the Orthodox and Catholic churches (much to the displeasure of the late Slavophiles and pan-Slavists). This was the logical extension of his version of Sobornost’, which he called vsetserkovnost’, or community of all within the church, which was necessary for the realization of the Kingdom of God on earth.

On the ethical question, closely related to the conception of wholeness or total-unity for Solov’ev is the idea of universal principles; crucial to his thinking is Kant’s Categorical Imperative, the testing of the validity of ideas by examining the possibility of their universal application; if idea can become universally binding or elevated into a universal principle and give beneficial results, then it can be approved, but if it fails this test it cannot. Solov’ev, as Sutton states,

taught that Christian values should be implemented throughout society, but in such a way as to preserve the worth and autonomy of the individual [in this sense he resembles Dostoevsky — and I would suggest that this is one of things that distances them both from Slavophilism – SJY]; he further taught that Christian teaching is concerned with active love. (Sutton, p. 39)

Note that active love is the key principle for the Christian life espoused by the Elder Zosima in Dostoevsky’s final novel.

So Solov’ev felt that the application to life for everyone of ethics derived from the Gospels was crucial in enabling the welfare of all and maintaining the autonomy of the individual (whilst balancing this with the needs of the collective). He saw a contrast between Christianity and other (i.e. secular) sources of ethics, and for example he compared Christian ethics to the ideals brought in by the French revolution, which promised freedom and equality, but were ultimately unable to guarantee human welfare. Essentially he suggests that the secular origins of revolutionary ethics led to an imbalance which meant they could not fulfil their goals, and even ended up going in the opposite direction.

This is one example of an attitude that holds a very important place in Solov’ev’ thinking: the rejection of one-sided views. Quite frequently he focuses on the negative impact of the tendency to adhere to a one-sided philosophy or views. He believed that in order to be objective, it was important to see things comprehensively and holistically, and this obviously relates to what I said moment ago about his emphasis on wholeness — this is the underlying imperative that drives development of his ideas and it is this that makes his philosophy significant.

The rejection of one-sidedness had a profound impact on all areas of his thinking. So, for example, he rejected a one-sided devotion to rationalism or empiricism within philosophy, seeing the first as pure thought without content, and the second as sensation without subject and specific content. (Because of this he rejected both leading forms of Western philosophy, and for this reason was appreciated by the late Slavophiles.) Synthesis was therefore always important to him, giving him an organic view of knowledge, in which different subjects and areas of knowledge are all linked to each other. The rejection of one-sidedness was also significant in relation to his views about the person and relationships between people, underlying his belief that one always has to take into account the feelings and needs of the other, which cannot be discounted in favour of one’s own desires and needs. So his ethics (on both the individual and communal level) derives from this basic belief in unity and the rejection of one-sidedness as well.

The most important dimension of this drive to wholeness can be found in his critique of different types of religion, which underlies his ideas in the “Lectures on Godmanhood.” In his conception there are deist religions and pantheistic religions. Deist religions such as Islam have a God that is transcendent, but not immanent (i.e. God is is in heaven, but not on earth and is wholly separated from man; God has no human aspect). Pantheistic religions, on the other hand, in which he includes Hinduism and Buddhism, have a God or gods that are in the world (i.e. immanent), but are not transcendent. One might dispute this, on the grounds that gods in Buddhism are a very peripheral issue, and both Nirvana and Karma can be seen as transcendent aspects of Buddhism, but that is another matter.

In essence the idea that this is a faith that focuses on material existence is correct, and in that sense Buddhism is very different from faiths that have a transcendent God. As Solov’ev sees it, the problem of deistic religions is that by separating God from his creatures, there are benefits for the spiritual life, such as the sense of awe in God and his creation, but there is little possibility of redemption or salvation, or of advancing beyond the condition of being one of God’s creatures. On the other hand, Hinduism and Buddhism, he suggests, express very well the dilemmas, tensions and obstacles of earthly existence, such as disease, pain, death, so they have a profound understanding of the human condition. This provides a reason for making progress with the spiritual life, but does not advance beyond diagnosing what is wrong with the world and human life, and offering remedies in ascetic or contemplative disciplines that lead to the idea of non-being. In other words, the only outcome of this type of religion for Solov’ev is renouncing the world.

In contrast to these faiths, Christianity has both transcendence and immanence. It is worth noting here that Solov’ev had a positive view of Judaism, which was quite unusual at the time, because he saw it as having same combination of immanence and transcendence; Judaism established this doctrine, which Christianity then fulfilled. The reason Christianity has this combination of immanence and transcendence is the figure of Christ, who is both divine and human. And this is the concept of Godmanhood (bogochelovechestvo). Solov’ev certainly did not invent this concept – it is, after all, central to the Gospels, but he did develop a specific theory in relation to it, based on the Trinitarian idea of the amalgamation of God, man and matter (Kornblatt and Gustafson, p. 11).

In essence one might suggest that this theory of Godmanhood is in fact a rewriting in theological language of his philosophy of all-unity (Gustafson, p. 31). The starting point for this theory is that because God is both transcendent and immanent, Christ is not simply a miracle-worker or prophet (Sutton, p. 60), or indeed an ordinary being of any kind; he is God made flesh, and the fact of his appearance on earth as a human being leads to a profound qualitative change in humanity and the natural order. In relation to the natural order, in the person of Christ, the historical process is fused with the cosmic one; as Christ enters the world and the historical process, he gives divine purpose to both (see Copleston, p. 63 on this). This suggests that history may have been entirely random before that moment – indeed it is tempting to say that according to this conception, history cannot really exist before the arrival of Christ on Earth (so we have a rather different role for religion in directing the course of history than we saw in Chaadaev’s conception, for example).

But more importantly, Christ’s appearance changes humanity, because His transfiguration, according to Solov’ev, anticipates and makes possible the transfiguration of all beings (Sutton, p. 60); it actually changes the nature of human life and the human body. Prior to Christ, corporal nature is purely physical, and therefore impenetrable (by this he means that the body has a sort of physical solidity that cannot incorporate anything else or occupy the same space as anything else – it is an object of resistance against other objects, and is closed off from all outside forces). The person is therefore also alienated (a term Solov’ev associates with evil) by the body’s earthly condition. As Sutton puts it:

The Incarnation of the God-man, Jesus Christ, among men, can alone counteract the effects of this alienation, [and] is the eminent means of salvation from creaturely existence. (Sutton, p. 47)

This is because after Christ, the human body contains an element of God’s transcendence, i.e., it is composed not only of physical matter, but also of spiritual matter, and these two cannot be separated.

This combination of physical and spiritual matter can be seen as another aspects of Solov’ev’s holistic thinking and rejection of one-sidedness, but it has a couple of other very important implications. The first is that it overcomes the idea – common to the Gnostic tradition of early Christianity thought and some other branches of the church – of the flesh (or the material world) as evil. Instead the flesh becomes spiritualized, so to speak, which is,

a universal process whereby eventually all material nature is “redeemed”; a spiritual aspect inheres in all forms of material being, and through divine action and the cooperative agency of conscious man, this spiritual aspect of matter will become fully manifest. (Sutton, p. 53)

Thus Solov’ev arrives at the idea of sacred corporality, which he also sees as an important part of Judaism’s emphasis on purification. It is this sacred aspect of the flesh that gives human beings the potential to be perfected, ultimately leading to the Kingdom of God on earth, moved by the collective spirit of Christian love (agape), which frees humankind from the natural (or animal) level of existence. The essence of sacred corporality is that the human being is now capable of penetration, i.e., the body loses its closed and resistant nature, and instead becomes receptive to outside (i.e. spiritual) forces. And this different quality of the transformed flesh is fundamental to the idea of resurrection, which is not a metaphor, but involves the raising of the physical body from the dead. This is what happened to Christ, so ultimately, human beings transformed by Christ must also gain this capacity. This question is central to the work of Nikolai Fedorov, as we shall see in our next lecture.

This question of the penetrability and potentially resurrectable nature of sacred flesh is one important aspect of the thinking underlying “The Meaning of Love.” The other important concept that animates Solov’ev’s thinking is the personification of divine wisdom, which he saw as having female form and named Sophia. Sophia, you may recall, was the subject of his visions, and I have to say from my reading, this is one area in which I find Solov’ev rather confusing. Perhaps this is not surprising, as this question very much relates to his religious experiences and his tendency towards mysticism. Like Godmanhood, Sophia is not an idea unique to Solov’ev. “Sophia” is the Greek word for “Wisdom; in the Bible there is a tendency to personify wisdom in female form; the Orthodox church tends to identify Mary Mother of God with divine wisdom; and Sophia was seen as the eternal feminine in the medieval Russian church. However, it was through Solov’ev’s emphasis on Sophia that “Sophiology” became a notable philosophical concept in the Russian tradition (see in particular, Sergei Bulgakov on this question).

Sophia is seen a vision of the beauty of the transfigured world and the divine cosmos, so she represents eternal rather than earthly beauty and is therefore an important aspect of total-unity. But it seems to be rather more complicated than this. Solov’ev also introduces two types of unity, the producing and the produced. The producing unity is logos, or God as an active force; the produced unity is Sophia, who represents the principle of humanity – not as an earthly phenomenon but as an archetypal, eternal idea – but who is also, as the opposition with logos suggests, a passive force. However, Sophia also appears in Solov’ev’s thinking as the active soul of the world and ideal humanity, and becomes a sort of bridge between God and humanity. As Copleston, who gives the clearest interpretation of the concept, puts it, Sophia is conceived within Godmanhood:

as the eternal ideal archetype of humanity, as the world-soul considered as actively engaged in realizing this archetypal idea, and finally as the fully developed divine-human organism. Sophia is depicted both as the active principle of the creative process and as its realized goal, the kingdom of God, the society of those participating in Godmanhood. (Copleston, p. 85)

So if Godmanhood is the principle of transformed flesh, becoming spirit, then Sophia is Solov’ev’s “attempt to embody the spiritual” (Matich, p. 64). Both sides of the equation therefore represent aspects of the principle of unity, but also indicate the role of the male-female opposition in his thinking. It should therefore come as no surprise that, guided by the spirit of total-unity, Solov’ev view the male and female as incomplete, and attempted to theorize their coming together as syzygy, which essentially means “conjoining”, and in the religious sense is a concept deriving from Gnostic mysticism. In Solov’ev’s conception signifies “close union.” As Hooper puts it, “his vision of ideal love is grounded in the reconciliation of body with soul” (p. 362), while Matich states: “Solov’ev viewed life’s task as reassembling the sundered body into a whole by reuniting male and female in a collective gender that is beyond sexual difference, a state that he affiliated with the figure of the androgyne.” (Matich, p. 71)

And this is the subject of “The Meaning of Love,” which attempts to rescue erotic love from its rejection by the church (and Tolstoy!) and place it above procreative love. He proclaims the power of the male-female pairing as a transfigurative force that will restore humankind in God’s image and overcome death (Matich, p. 73).

As Hooper puts it:

Divine in origin, eros can, in its most perfect manifestations, bind two separate people together into a single individuality, restoring them each to wholeness and propelling them towards ever-closer harmony with the cosmic all-unity (vseedinstvo), which is God. (Hooper, p. 361)

So in our seminar, we shall focus on how he constructs that argument, and compare his view to that of Tolstoy in the “Postface to The Kreutzer Sonata.”

Sources

Bulgakov, Sergei, Sophia, the Wisdom of God: An Outline of Sophiology (Lindisfarne Books, 1993).

Copleston, Frederick, Russian Religious Philosophy: Selected Aspects (Notre Dame: Search Press, 1988)

Hooper, Cynthia, “Forms of Love: Vladimir Solov’ev and Lev Tolstoi on Eros and Ego,” Russian Review, 60.3 (2001), 360-80

Gustafson, Richard F., “Soloviev’s Doctrine of Salvation,” in Russian Religious Thought, ed. Judith Deutch Kornblatt and Richard F. Gustafson (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), pp. 31-48

Kornblatt, Judith Deutch, and Gustafson, Richard F., “Introduction,” in Russian Religious Thought, ed. Kornblatt and Gustafson (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), pp. 3-24

Matich, Olga, Erotic Utopia: The Decadent Imagination in Russia’s Fin de Siècle (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005)

Mochul’skii, Konstantin, Vladimir Solov’ev: Zihzn’ i uchenie (Paris: YMCA Press, 1951)

Solov’ev, Vladimir, “The Meaning of Love” (1892-4), in J. M. Edie, J.P. Scanlan and M.B. Zeldin, eds., Russian Philosophy, 3 vols (Chicago, 1965), III: 85-98 | Smysl liubvi [Russian text]

Sutton, Jonathan, The Religious Philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov: Towards a Reassessment (Basingstoke: MacMillan, 1988)

Tolstoy, Leo, “Postface to The Kreutzer Sonata,” in The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories, trans. David McDuff (London: Penguin, 1985), pp. 267-82