Readings: Nikolai Chernyshevsky, extracts from “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy” (1860); Dmitry Pisarev, “The Realists” (1864) and “The Thinking Proletariat” (1865)

We’re now moving away from the debate that arose initially out of Chaadaev’s “First Philosophical Letter” and dominated Russian intellectual life in the 1830s and 1840s. In the next generation a different set of questions and ideas dominated, although we can still in many ways characterize their main preoccupation as being with “the person” – one of our key themes. For the Westernizers, the question of the person had taken its most prominent form in Herzen’s emphasis on freedom, while for the Slavophiles, the individual was subordinated to the collective, so here we can perhaps refer to the context in which the human being lives. For the next generation, the question of human nature itself comes to the foreground, but this also leads to ideas about the collective, and in particular the possibility of social reorganization for the sake of the human being. And in this latter question you can see that we are moving more firmly into approaches to changing the world, rather than just discussing it.

As we enter the 1850s, the intellectual landscape already looks very different; the Slavophiles were still around, but the Westernizers no longer existed as a group: Belinsky died in 1848, Herzen was living in exile in Europe, and Bakunin, after taking part of the revolutions of 1848, was arrested in Dresden in 1849, deported to Russia, and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in Petersburg. Gogol’s death in 1852, and Dostoevsky’s imprisonment, heralded significant changes in the literary scene as well, with the newer prose writers Ivan Goncharov (1812-1891), Ivan Turgenev (1818-18883), and Lev Tolstoi (1826-1910) coming to prominence, alongside the playwright Alexander Ostrovsky (1823-1886) – firmly establishing the age of realism. The political environment was also very much in the process of transition in this period. Following the oppressive reign of Nicholas I, the accession of Alexander II in 1855 ushered in an era of reform, spurred on, in particular, by defeat in the Crimean war. This led, most significantly, to the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, but also to judicial and local government reforms.

It was in this context that a new generation of radicals emerged. They are often referred to as the shestidesiatniki (generation of the 1860s), although in fact the important years here are 1855-1866, their ascendency ending with attempted assassination of the Tsar by Dmitry Karakozov in 1866, which resulted in greater radicalization of the left and the end of government reforms. The radicals from this period called themselves the “Enlighteners” (prosvetiteli), to indicate their links with the eighteenth-century rationalists. But they are perhaps best known as the Nihilists, the term popularized by Ivan Turgenev in his novel Fathers and Sons, whose main character Bazarov, is a young doctor devoted to scientific experimentation and empirical evidence as the only basis for knowledge. He rejects received ideas, traditions and standards of behaviour, and states that “a good chemist is twenty times as useful as any poet” (Turgenev, p. 42). As Copleston (p. 102) states:

the term [Nihilist] referred to those who claimed to accept nothing on authority or faith, neither religious beliefs nor moral ideas nor social and political theories, unless they could be proved by reason or verified in terms of social utility. In other words, Nihilism was a negative attitude to tradition, to authority, whether ecclesiastical or political, and to uncriticized custom, coupled with a belief in the power and utility of scientific knowledge.

So the Nihilists were thinkers who, like Herzen, emphasized knowledge. They were therefore not revolutionaries as such – none of them was directly involved in revolutionary activity – but they rejected what they saw as the timidity and liberalism of the previous generation in favour of a much more radical position. Their success in articulating a new radicalism can be judged by the fact that their writing became very important in kick-starting the revolutionary movement, and this is also reflected in the fact that the term “Nihilism” became synonymous with “revolutionary” way beyond Russia’s borders in the second half of the nineteenth century. For a very curious example that indicates the level of interest in Russian Nihilists in British culture in the late nineteenth century, see here.

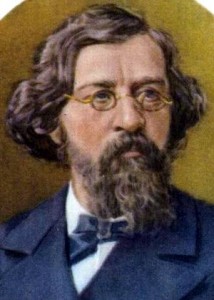

The leading figure of the original group of Nihilists was Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-1889), a priest’s son from Saratov, who attended his local theological seminary prior to studying philosophy and history at Petersburg university, where he became influenced by Belinsky and the French Utopian socialists, and gradually lost his Christian faith. His main philosophical works were “The Aesthetic Relationship of Art to Reality” (1855) and “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy” (1860), but his radicalism precluded a university career, and after a stint working in a high school, he began working for the most prominent radical journal, Sovremennik (The Contemporary), and shifted towards more polemical and literary-critical writing. The Nihilists can be seen as the original source of Bolshevism (Ulam, p. 28), but a lot of their writing concerned literature and used ostensibly literary topics to debate radical ideas (thereby following in the footsteps of Belinsky, whose heirs they proclaimed themselves; Venturi, p. 143). This was certainly true of the two other main figures in this movement, Nikolai Dobrolyubov (1836-1861) – like Chernyshevsky the son of a priest – and Dmitry Pisarev (1840-1868), who was from a noble family fallen on hard times. Both Chernyshevsky and Pisarev were arrested in 1862 – the former for connections to the first revolutionary organization Zemlia i volia (Land and Will) and to Herzen, the latter for trying to publish a proclamation defending Herzen and calling for the destruction of the monarchy. Pisarev spent four and a half years in the Peter and Paul Fortress, and drowned shortly after his release (this was possibly suicide). Chernyshevsky was sentenced to hard labour and spent most of the rest of his life in Siberia, returning to European Russia only in 1883; because of his treatment he became a revolutionary martyr. So they were viewed as dangerous figures. For this lecture, focusing mainly on Chernyshevsky, I want to examine what it was about their thinking that was so radical, and the role of the artistic debate in that. I will touch on how they influenced subsequent generations of revolutionaries, but I am going to deal solely with the philosophical/literary origins of this movement and not on Chernyshevsky’s political writings on Populism and the Russian commune, where he was also very influential (Populism will be the subject of the first lecture next term).

The starting point for the Nihilists’ thinking may not seem particularly revolutionary:

The Nihilists […] sought the liberation of human beings from shackles imposed on them by social convention, the family and religion, but they believed that this goal would be attained through the spread of a scientific outlook (Copleston, p. 103; my emphasis).

But this emphasis on science certainly was revolutionary, because advances in science in the nineteenth century, such as the development of evolutionary theory and discoveries in biochemistry, were overturning traditional views of the world and of human existence. In “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy,”

Chernyshevskii discusses what were in his time the most recent and thrilling discoveries of the chemists […]. He outlines the findings that plant, animal and human tissues are complex chemical substances, “organic compounds,” “carbon compounds,” in no way different from the organic compounds of metal and rocks. (Randall, p. 76).

The implications of these findings are crucial, as they allow Chernyshevsky to assert the material basis of human nature:

The idea, formulated by the natural sciences, of the unity of the human organism serves as a principle of the philosophical view of human life and all its phenomena; the observations of physiologists, zoologists and physicians have removed any idea of dualism in man. Philosophy sees in man what medicine, physiology and chemistry see in him; these sciences demonstrate that no dualism is apparent in man and philosophy adds that if man did have another nature, beside his real one, then this nature would necessarily reveal itself in some way, and since it does not reveal itself in any way, since everything that occurs and manifests itself in man occurs in accordance with his real nature alone, he has no other nature.’ (Chernyshevsky, “Anthropological Principle,” p. 213)

In his dismissal of “dualism” here, Chernyshevsky is rejecting the idea of a body/soul or body/spirit dichotomy. The implication of this could not be mentioned openly because of the censorship, but is quite plain: in proclaiming that no spirit or soul exists, he is also proclaiming that God does not exist (one of the reasons he refers frequently to Greek myths in this text is in order to allude covertly to what he views as the mythical basis of Christianity). The religious view of humanity is therefore replaced by a scientific one of “bodies that functioned as physiological machines.” (Pozefsky, p. 29)

As well as defining his position in opposition to tradition and conservative thinking, Chernyshevsky’s atheism has significant implications for his view of human behaviour and morality; as there is nothing beyond material being, ethical behaviour cannot be contingent on God. Abandoning faith in God meant relying on man to change society (Frede, p. 135), so a material basis had to be found for both ethical action and its evaluation. This, indeed, advances humanity and society; as Pozefsky states, Chernyshevsky, “believed that a reigning ethos which subordinated corporeal needs to religious piety hindered the development of the individual and society.” To counter this, “he preached an anthropological philosophy that placed physical man at the foundation of morality.” (Pozefsky, p. 28)

It is the impulse to find a material basis for ethics that leads to the development of Chernyshevsky’s philosophy of rational egoism. Based on a version of utilitarianism that equates the good with the pleasant, and assuming that the physical environment or circumstances determine behaviour, rational egoism claims that human beings are guided purely by self-interest:

a man is good when in order to gain pleasure for himself he has to do what is pleasant for others; he is bad when he is forced to derive his pleasure from the infliction of what is unpleasant for others (Chernyshevsky, “Anthropological Principle”, p. 217).

Behaviour is “rational” insofar as people are purely physiological beings who perceive their own interests and, without any internal conflict (because there is no spirit potentially at odds with the body’s impulses), act in such a way as to fulfil them. To counter the argument that the outcome of human actions are not knowable, and that it is therefore impossible to behave perfectly rationally in one’s own (or anyone else’s best interest), Chernyshevsky again invokes scientific advancement to insist this will soon be possible:

Chernyshevsky’s concern [is] to persuade the reader of the general applicability of the scientific method […]. Iron laws as rigid as those employed in the study of nature’s chemical composition could be applied to the study of history, society and man’s behaviour. […] The “alliance of the exact sciences, under the direction of mathematics, that is counting, weights and measures,” extended every year to new areas of knowledge, and even the moral sciences were now entering it. Once the new method had conquered so much territory there seemed to be no reason why man’s future history could not be regulated with its assistance: it ought to be possible, if one gathered enough information beforehand, to predict “with mathematical exactitude” the results of contemplated change (Offord, p. 518).

Much of Chernyshevsky’s reasoning involves taking examples from the animal world to compare to human behaviour, or extrapolating from very straightforward moral dilemmas, to prove his points. He can be criticized for this – the examples he uses often seem trivial, there are frequently holes in his reasoning, and he often seems to over-egg the pudding of physiological reductionism. But for all the faults in his reasoning, what he is trying to do is significant: to apply the scientific method consistently, in order to show how it can be used to enhance the study of mankind, and to suggest that such methods will ultimately become commonplace. The reason we find it difficult to accept his examples, his argument implies, is that we are simply unused to this new type of reasoning and are judging it in the light of old-fashioned beliefs in God and human duality. Nevertheless, a lot of his reasoning now looks very facile and suspect.

Another criticism is that rational egoism appears to advocate individual self-assertion, and therefore be very far from a civilized or social ethical system. Chernyshevsky gets round this by stating that the same principle applies on a larger scale, with society standing above individual interests, and mankind as a whole above society. He claims that acting against the interests either of the individual or these broader groups results in self-destruction; if individuals do not behave socially, therefore, “their individual pleasure-seeking will be thwarted and [they] will be destroyed” (Randall, p. 85). Thus what is in the best interests of society is in the best interests of the individual, and the enlightened person will see this and act accordingly, fulfilling both at the same time. This concept of selfishness in the service of others is developed in Pisarev’s 1865 essay “The Thinking Proletariat,” which we’ll discuss in our seminar.

Thus far from being individualistic, this philosophy is aimed at transforming society, and is implicitly revolutionary (such things can never be stated openly) because it suggests that it is only by removing the inequalities of life (the circumstances that cause some people to behave badly and harm others), that a situation will be reached where nobody will need to harm others because and everybody’s interests will be the same, and their pleasure-seeking will not conflict with anybody else’s (Randall, p. 81). Given then entrenched inequalities and conflicts of life, such a situation could only come about through a revolution.

The philosophy of rational egoism that Chernyshevsky expounded in his essay “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy” found its clearest expression in his 1863 novel What is to be Done? (Chto delat’?), which he wrote in prison and which was published in Sovremennik after a comedy of errors involving the police, the publishers and the censors (see Katz and Wagner, pp. 22-3). What is to be Done? was an absolute hit, and it is no exaggeration to describe it as the most influential novel of its time in Russia; certainly, in terms of its social and ideological impact it was much more significant than the other major works of the decade, which, let us not forget, included Crime and Punishment, War and Peace, and Fathers and Sons. It is also overlong, tendentious, poorly written, with wooden characters behaving improbably in improbable situations. It describes a group of young people from Petersburg, who arrange their lives on rational principles. There are marriages of convenience to escape tyrannical parents and enable prostitutes to reform, and a sewing co-operative is formed to pool resources and profits for the benefit of all: “enlightened individuals recognized that the maximization of society’s interests also best served their personal interests because their welfare depended directly on society’s general level of prosperity.” (Katz and Wagner, pp. 17-18).

There is a steadfast revolutionary, Rakhmetov, a superhuman figure who eat unfeasible amount of raw meat and sleeps on a bed of nails to strengthen his mind and body, but the main characters are essentially ordinary – the implication being that anyone can follow their example. And people did indeed try to emulate the book, setting up communes and co-operatives to live according to the same rational principles – although these attempts were largely unsuccessful. Nevertheless, What is to be Done? became almost a handbook for revolutionary activity, and was so important to Lenin that he named his 1902 treatise on party organization in its honour.

In the depiction of the “new people” who illustrate the idea of rational egoism, the novel exemplifies one of the bases of Chernyshevsky’s aesthetics (which I’ll discuss in more detail later), that art can project a desirable future situation that does not exist yet (see Scanlan, p. 10), and as such in addition to its contemporary influence, it also acts as a precursor to one of the central tenets of socialist realism, of depicting what Andrei Zhdanov, in his speech to the congress of the union of Soviet writers in 1934, described as, “reality in its revolutionary development.”

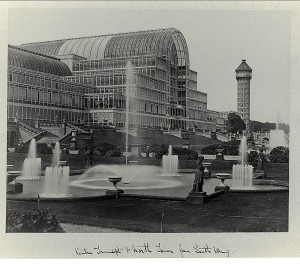

But the novel goes further than this, because it also contains an image of society transformed, after the revolution. Vera Pavlovna’s Fourth Dream portrays a socialist utopia of equality, communal life, pleasurable work for the good of all, and joyful leisure – including references to free love (which were racy enough to lead to this chapter of the book being removed from an early translation into English). We will return to the utopian aspects of this dream in more detail next term, but in terms of the immediate debates in the 1860s, its depiction is significant for two particular reasons. The first is that this dream in the novel describes the Crystal Palace as the only present-day building that resembles the glass and steel palace that future generations will live in. Built in Hyde Park for the 1851 Great Exhibition, and then relocated to Sydenham in South London, the Crystal Palace was seen as an extraordinary symbol of modernity and progress. It was widely discussed in the Russian press in the 1850s, and Chernyshevsky wrote a review of its building, contents and grounds for Sovremennik after the reopening in Sydenham in 1854 (I discuss this here). But it was in the 1860s that it became a very prominent literary image, through Chernyshevsky’s utopian vision and Dostoevsky’s counter-argument, in Notes from Underground and elsewhere, that the Crystal Palace represents not humankind’s freedom, but its enslavement (which I will discuss in more detail in the next lecture). Through that debate, the Crystal Palace achieved iconic status in Russian literature, and its utopian and dystopian associations continue into the twentieth century with Evgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 novel We, where the buildings of OneState are made of glass and enable permanent surveillance. So while one might criticize the literary merits of What is to be Done?, it certainly had a lasting effect on literature beyond its social impact.

The second reason why the dream is significant is that it presents an image of gender equality; the heroine, Vera Pavlovna, dreams of the progress of society towards the emancipation of women, and the novel throughout advocates women’s rights as an essential component of the liberation of society as a whole – indeed, the main plot revolves around Vera Pavlovna’s journey towards social and personal emancipation:

Chernyshevsky believed […] that if this revolution was to succeed, it would need to overturn the patriarchal relations that existed within the family as well as between social groups and between the state and society. Thus he became an ardent advocate of women’s rights as a means to pursue social revolution generally, and thereby helped to raise the “women’s question” in mid-nineteenth-century Russia. (Katz and Wagner, p. 14)

From the 1860s onwards, a significant number of women became actively involved in the revolutionary movement – in particular in Narodnaya volya (The People’s Will) and subsequently the Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) and Mensheviks (Cathy Porter’s study Fathers and Daughters is a very readable account of women revolutionaries), and the role of Chernyshevsky’s novel in initiating that process and providing a model for young women to emulate should not be underestimated.

The effect What is to be Done? had on literature and society is all the more remarkable given what a bad book it is, but it does indicate the importance of literature and art in the development of ideas in Russia, confirming Belinsky’s notion of the social role of literature. Central to Chernyshevsky’s aim was educating readers through his fiction and journalism to participate in the transformation of society (Frede, p. 135). And his aesthetic theory ultimately contributes to that; “The Aesthetic Relationship of Art to Reality” has more to do with changing reality than with aesthetics, as it is aimed at introducing a mode of thinking that will lead to revolutionary activity:

under the disguise of an aesthetic treatise he wanted to encourage man to abandon romantic dreams which always accompany “a man in a false position” […] he urged the reader not to be deceived by useless perfection, but rather to create a realistic mentality (Venturi, p. 142).

Built, like his rational egoism, on a scientific outlook, “the crux of [Chernyshevsky’s] materialist aesthetics was the assertion that since it is not possible for the mind to conceive of anything that cannot be perceived by the senses, nothing can be more beautiful than what is in nature” (Pereira, p. 40).

As man is, in Chernyshevsky’s theory, the only absolute value, material existence is privileged over (non-existent) abstractions such as the spirit. Therefore he has a much more concrete view of reality – hence also of realism – than was the case for earlier thinkers:

The most general thing of all that is dear to man, and the thing most dear to him on earth is life; in the most immediate way the life he would like to lead; then any life, because it is better in any case to be alive than not to be alive […] And it seems that the definition “the beautiful is life”; “beautiful is that being in which we see life as it should be according to our concepts; beautiful is that object which manifests life in itself or brings life to our minds” – it seems that this definition satisfactorily explains all instances that arouse in us a sense of the beautiful (Chernyshevsky, “The Aesthetic Relation of Art to Reality,”, pp. 286-7; in Leatherbarrow and Offord, p. 199).

Moreover the notion of beauty he establishes is clearly socially constructed, as we see in his comparison of the robust beauty of the peasant girl and the pallid, weak ideal of aristocratic beauty that proclaims the woman’s unfitness for work (Chernyshevsky, “Aesthetic Relation,” pp. 287-8; in Leatherbarrow and Offord, p. 199). Again we can see here the revolutionary subtext of challenging élite notions of art (and life) and replacing them with down-to-earth, realistic conceptions.

Placing this form of realism in the context of previous theories of art, Offord notes (p. 515) that:

Chernyshevsky proceeds to attack the Hegelian aesthetic which postulates the existence of a beauty superior to that in everyday reality and accessible through art. His rejection of this aesthetic involves inversion of the relationship it describes between beauty and reality. Beauty for Chernyshevsky is inferior to reality. It is redefined as that which is most suggestive of life in its healthy manifestations. The pursuit of beauty conceived in the Hegelian way is for him a quest divorced from contemporary reality. The function of art becomes correspondingly menial: art should merely reproduce reality, introduce people to concepts unfamiliar to them, serve as a “handbook for the person beginning to study life,” and, Chernyshevsky adds, contribute by its examination of reality to the improvement of man’s condition.

Art’s only role, therefore, is in relation to the reality it reproduces or represents:

an object or an event may be more intelligible in a poetical work than in reality, but the only merit we recognize in that is the clear and vivid allusion to reality; we do not attach independent significance to it as something that could compete with the fullness of real life (Chernyshevskii, “Aestheitc Relationship,” p. 374).

The realist basis of Chernyshevsky’s aesthetic theory links it to Belinsky’s, but he subordinates art to life, so that art becomes little more than an aid to studying life, and therefore is a somewhat inferior substitute for life; reality is always seen as superior to the reproduction. His views have for this reason come in for a good deal of criticism, and are not seen as comparable with his predecessor’s more rounded view; Victor Terras (p. 237) rather snottily asserts that Chernyshevsky’s “argument is that of a man who is not only uninterested in art, but who actually has never bothered to find out what art is. It is the argument of a man unfamiliar with aesthetic experience.” When faced with a writer who viewed Nekrasov as a greater poet than Pushkin, because the former wrote for the people, while the latter did not (Ulam, p. 32), or one who apparently saw no difference between appreciation of the female form and appreciation of a work of art (as his frequent recourse to examples of female beauty suggests), we may be forced to agree. And such a view may perhaps be applied even more readily to Pisarev. He may be caricatured in the statements falsely accredited to him about boots being more useful than Pushkin, and a real apple being more beautiful than a picture of an apple, but in many ways his real views are hardly less utilitarian. It is hard sometimes to see beyond his apparently philistine dismissal of art.

But the fact that these thinkers worked primarily in the field of literary criticism suggests that they did see some use for art, and that there is more to their outlook than initially meets the eye. James Scanlan (pp. 6-9) shows the nuances in their theories by examining them in context. Thus he argues that Chernyshevsky’s idea that art has to have human significance, that realism must be employed in the service of human needs, that art has a didactic duty to explain reality and moral duty to evaluate it, should be viewed in the context of the reality of the time that could not be mentioned openly, the Crimean war. Although we may question whether this explaining and evaluating function is a sufficient definition of art, or whether the content of art should be found in real life alone, Scanlan notes that is can be seen in this light, and that, for example, the realist art of the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers) takes its cue from Chernyshevsky’s ideas.

Moreover Scanlan notes that Pisarev’s call for the destruction of aesthetics emphasizes precisely aesthetics, by which he meant,

art that was frivolous or merely routine – something that is a product of sheer caprice, habituation, or inertia and that consequently has no enduring foundation in human life. Aesthetics for Pisarev is the sphere of what pleases people for no good reason (Scanlan p. 2).

So in effect Pisarev’s attack, for all his radical statements, is on art that is not socially conscious, and like Chernyshevsky, he emphasized the social and scientific value of art, viewing the true artist as a thinker who contributes to debates about the development of society, and ultimately changes that society.

Thus when confronted with criticisms such as, “in Černyševskij, in Dobroljubov […] one finds only too often statements to the effect that the moral and ideological merits of a given work allow one to overlook its stylistic deficiencies” (Terras, p. 176), we should be cautious. On the one hand Terras has a point, but on the other, this is judging socialist art (and art criticism) according to the criteria of bourgeois art, and therefore misses the point entirely; one of the most significant problems of bourgeois art, in the view of critics like Chernyshevsky and Pisarev, is its petty concern with stylistics, which diverts attention from the burning questions of society and leaves the status quo undisturbed. By definition, works which do not exhibit this failing but instead emphasize the social context and content are, for the nihilist critics, inevitably superior, because they provide necessary components for the improvement of society.

That does not, however, mean that their theories were without flaws. They tend to look rather naïve, because their treatment of literary texts as essentially sociological documents leads to them discussing fictional characters as though they are real people in real situations. And frequently their sociological analysis cannot account for any complexity or nuance in a text; thus Dobrolyubov’s very famous article on Goncharov’s novel Oblomov, “What is Oblomovitis?” (1859), may be very perceptive in establishing the connections between Oblomov and earlier “superfluous men” such as Evgeny Onegin and Pechorin from A Hero of our Time, but in in suggesting this shows the need for action and change, Dobrolyubov ignores the fact that the idle dreamer Oblomov is far a far more attractive and vivid character than the active, practical realist Stolz. Such criticism frequently cannot take account of the whole text, and therefore can be accused of presenting a distorted view. (However, one should note that all literary criticism is selective in this way; perhaps Nihilist criticism is just more open about its tendentious aims!)

Nevertheless, sociologically-focused essays like Dobrolyubov’s study of Oblomov, and Pisarev’s discussions of Bazarov from Fathers and Sons, Rakhmetov from What is to be Done?, and Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment, did have an important impact in their time. It is significant that the focus of these literary-critical works was characters, emphasizing their view of the foundation of literature in human life and its role in providing models (positive and negative) for behaviour. And it’s the connection of those two questions, of human life and literature, that will form the basis of our discussion next week; we will use the seminar to explore: 1) the validity of Chernyshevsky’s view of human nature in “The Anthropological Principle”; and 2) the ways in which Pisarev develops Chernyshevsky’s ideas and places them within a literary context.

Sources

Chernyshevsky, Nikolai, “The Aesthetic Relation of Art to Reality,” in N. G. Chernyshevsky, Selected Philosophical Essays (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1952), pp. 281-381 | “The Aesthetic Relationship of Art to Reality” [extracts] in A Documentary History of Russian Thought From the Enlightenment to Marxism, ed. W. J. Leatherbarrow and D. C. Offord (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1987), pp. 199-202 | Russian text

Chernyshevsky, Nikolai, “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy” [extracts], in A Documentary History of Russian Thought From the Enlightenment to Marxism, ed. W. J. Leatherbarrow and D. C. Offord (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1987), pp. 213-222 | Russian text

Chernyshevsky, Nikolai, What is to be Done? [A Vital Question] | Russian text

Chernyshevsky, N. G., other texts in Russian

Copleston, Frederick, Philosophy in Russia: From Herzen to Lenin and Berdyaev (Notre Dame: Search Press, 1986)

Dobrolyubov, Nikolai, “What is Oblomovism?” | Russian text

Dobroliubov, Nikolai, other texts in Russian

Frede, Victoria, Doubt, Atheism, and the Nineteenth-Century Russian Intelligentsia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011)

Katz, Michael R., and Wagner, William G., “Introduction: Chernyshevsky, What is to be Done? and the Russian Intelligentsia,” in What is to be Done?, trans. Michael Katz (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989), pp. 1-36

Offord, D., “Dostoyevsky and Chernyshevsky,” Slavonic and East European Review, 57 (1979), pp. 509-30

Pereira, N. G. O., The Thought and Teaching of N. G. Chernyshevskii (The Hague: Mouton, 1975)

Pisarev, Dmitrii, texts in Russian

Porter, Cathy, Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (London: Virago, 1976)

Pozefsky, Peter C., The Nihilist Imagination: Dmitrii Pisarev and the Cultural Origins of Russian Radicalism (1860–1868) (New York and Oxford: Peter Lang, 2003)

Randall, Francis B., Chernyshevskii (New York: Twayne, 1967)

Scanlan, J.P., “Nikolaj Chernyshevsky and the philosophy of realism in nineteenth century Russian aesthetics,” Studies in Soviet Thought, 30 (1985), pp. 1-14

Terras, Victor, Belinskij and Russian literary criticism: the heritage of organic aesthetics (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1974)

Turgenev, Ivan, Fathers and Children, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Macmillan, 1895) | Russian text

Ulam, Adam B., Ideologies and Illusions: revolutionary thought from Herzen to Solzhenitsyn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976)

Venturi, Franco, The Roots of Revolution: A History of the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth-Century Russia (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1960)