Seventy-five years ago, on 30th November 1936, the Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire. Contemporary newsreels give a good impression of the events of that evening:

You can also see the Pathe newsreels here, and parts of the Crystal Palace is on Fire video made by the Crystal Palace Foundation.

What really struck me as I was looking for accounts and images of the fire is the extent to which it was and continues to be seen as a spectacle, comparable with all the palace’s previous performances. This letter by Edgar McWilliam, written the day after the fire, describes traffic and pedestrians surging up the hill to watch. The report from The Guardian on 1 December 1936 also focused on the crowds of on-lookers:

The immensity of the crowd destroyed the possibility of evacuating the area around the tower. Anerley Hill, where the tower was most likely to fall, was one solid, seething mass of people. Mounted and foot police struggled to force the crowd back. Even the fire engines were hemmed in. […] It was a strange crowd which came out to see the end of a famous London landmark. There were the connoisseurs forearmed with a knowledge of local topography. There were the sort of young men and women to be seen at almost any free entertainment in the streets. There were vast numbers of cyclists, both men and women. There were youngish men and women with traces of Bloomsbury, Hampstead and Chelsea in their clothes and speech, taking the whole affair very gravely. But among these were to be seen many elderly men and women to whom the destruction of the Palace meant the end of a chapter in their lives.

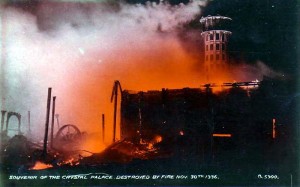

That sense of both the spectacle of the fire, and what the building meant to people, is also apparent in this lovely animation, The Crystal Palace is on Fire, by Peter Rest. And this ‘souvenir’ postcard of the fire is a good indication of the perception of the fire as the palace’s final performance:

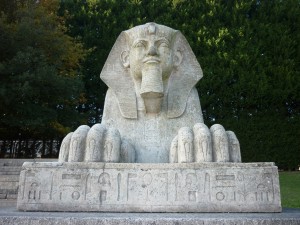

This all seems to present a distinct contrast with how the fire was reported internationally, where it seems its significance wasn’t always understood, as a feature in Life magazine, 23 December 1936, shows (pp. 33-35). Describing the palace as a ‘gigantic greenhouse,’ the article rather sniffily labels one of the pictures, ‘Wreckage of Crystal Palace art consisting of hideous plaster copies from the Egyptian, Greek, Pompeian, Byzantine and Gothic. If it had been real art, the fire would have done a billion dollars damage’, which rather misses the point. Here, the spectacular nature of the fire lies merely in its size, but the innate sense of the palace itself as a show, and its copies as architectural, archaeological and artistic theatre, eludes the author.

Seventy-five years later, the sphinxes and statues adorning the terraces have been transformed from archaeological pastiche to real ruins, but that sense of spectacle is still apparent.

Walking through the ruins gives a taste of what an extraordinary sight the palace must have made. It indicates how powerful the trace of something that has essentially vanished can be. In the case of the Crystal Palace, I think that’s because its real power lay not in Joseph Paxton’s innovative design for the iron-and-glass structure alone – it was always its appeal to the imagination that mattered most.