In this post, the penultimate in the series, instead of focusing on a single figure, I’m going to explore one of the lines that connects Russian radicals, and in particular their agitational/publishing activities, to the work of their Russian-Jewish counterparts. Some may suggest that this stretches the definition of ‘Russians’ too far, as Jews would not have identified as Russians, but I have my reasons. Certainly, Rudolf Rocker questions this last assumption:

It was incredible to me that people who had suffered so much in Russia, where Jews were treated as pariahs from the cradle to the grave, should retain such affectionate feeling for the country. These Jewish proletarians seemed to belong in spirit still to Russia. It could hardly be called patriotism. It was love of their native places, of the towns and villages where they had grown up and spent their early years. (p. 93)

The Rusian Socialist Group’s Appeal to Public Opinion equally observes Russian Jews’ ‘deep-roooted love for the country of one’s birth’, ‘in spite of the regime of tyrannical oppression’ they had escaped, and that many refugees retained economic ties with Russia (p. 17). Aside from revealing more complex feelings about Russia than one might expect, these quotations also indicate another reason for including Jews: the oppression they suffered placed them, regardless of their politics and religious views, in a similar position vis-a-vis the Russian government to that of the radicals. Indeed, Russian government rhetoric frequently lumped Jews and radicals together (Appeal, pp. 15-16, Rocker, p. 87), in order to justify the persecution of both groups and incite the general population against them. This, in turn, created a common cause; we saw in a previous post that Kropotkin spoke at protests against Jewish oppression, and his was not a lone voice. The various socialist clubs that sprang up around the East End in these years were (unlike the Russian socialist parties, it must be said) diverse and tolerant establishments where Russians and Russian Jews would regularly meet and interact. As Halpern and Reinharz point out:

Jewish workers were virtually the only Eastern Europeans among whom a Russian radical could conduct propaganda and agitation. The intelligentsia in these cities did not have to seek out the people idealistically, like the populists in Russia, but were thrown in with them by necessity, since many of them had to become proletarians in order to support themselves (p. 225).

So it is difficult to exclude the Jewish component of radical activity from the Russian one, and, I would argue, limiting to attempt it. I should note that my definition of ‘Russian’ is also flexible in that, as I consider the question of persecution by the Russian state to be significant, by ‘Russia’ I mean the Russian Empire, i.e. including parts of Belarus, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania etc, rather than the territory of what we now call the Russian Federation.

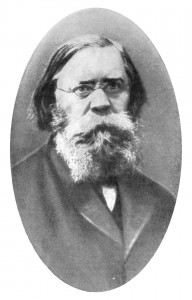

Pyotr Lavrov, the narodnik (populist), was, in any case, definitely ethnically Russian. He was perhaps most famous for his Historical Letters (1870), which in great part inspired the ‘going to the people’ movement in the 1870s. By this time Lavrov was already living in Europe, having escaped from exile in 1868. He lived mainly in Paris and Zurich, but also spent a couple of very important years in London. His first visit was in April 1871, during the Paris Commune; he was sent first to Brussels ‘to seek aid for the Commune from the General Council of the International’ (Pomper, p. 122), and from there went to London to visit Marx and Engels. Lavrov’s relationship with Marx is the subject of some disagreement. Pomper states that the two men ‘established lasting, if not always cordial or friendly relations’ (p. 122), but Eaton paints a more positive picture, describing them as ‘good friends’ despite some ideological disputes, and pointing out that it was to Lavrov that Eleanor Marx gave her father’s Russian books after his death (p. 102). Certainly it appears to be the case that Marx did not entertain the sort of hostility towards Lavorv that characterized his relations with other Russians, and it seems quite likely that ‘Lavrov’s radical assessment of the significance of the Commune as a new form of proletarian government actually influenced Marx’ (Pomper, p. 123). Paradoxically, Soviet historians and Marxist-Leninist theoreticians, obliged to emphasize Marx’s primacy in all things, played down any such influence.

Lavrov saw himself primarily as an internationalist rather than a Russian socialist (Kimball, p. 32), but as the spiritual father of the more moderate wing of Russian populism (as opposed to the Bakuninist insurrectionists), he felt he had no choice but to take on editorship of the Russian socialist journal Vpered! (Forward!) in 1872. It was this that brought him to London, along with his assistant Valerian Smirnov in March 1874. They moved from Zurich with the journal’s printing equipment to Tollington Park, near Finsbury Park. According to Fishman, the flat was at no. 3 (p. 102), but he has the dates wrong, referring to December 1875. But in Spring 1875, Pomper states, the journal had moved round the corner to 3 Evershot Road (p. 173). It was to move again, in May 1876, also round the corner, to 57 Fonthill Road (Pomper, p. 198). This was, I think, the first Russian commune in London. For the next two years or so, the editors and writers of Vpered! lived and worked alongside the compositors: ‘There were no salaries, and everyone shared both menial and intellectual work – athough Lavrov exhibited such incompetency in the former area that his colleagues were always quick to relieve him of any manual task’ (Pomper, p. 174). This does rather bring to mind certain academics who manage to wriggle out of administrative duties with similar displays of incomptence, but by all accounts Lavrov was a very endearing figure, as this assessment by Turgenev suggests: ‘The words are terrible, but the glance is gentle, the smile is most kind, and even the enormous and unkempt beard has a tender and peaceful character’ (letter to Annenkov, 1879, cited in Pomper, pp. 125-6).

His peaceful beard notwithstanding, Lavrov’s relations with Smirnov were not particularly warm: the latter ‘apparently had no feelings of friendship for Lavrov, but regarded him as the only suitable editor for the journal and refused to see it fall into the hands of less competant thinkers and writers. Smirnov seems to have been more concerned with guarding the integrity and dignity of the journal than anything else’ (Pomper, p. 193). Lavrov, meanwhile, considered himself much more a thinker than a propagandist, and found the work on the journal a terrible strain. But he continued to produce articles for Vpered!, including ‘To Whom Does the Future Belong? A Conversation of Logical People’ (Komu prinazdlezhit budushchego? Razgovor posledovatelnykh liudei, 1874), a curious dramatized debate between different factions and types. It’s perhaps most notable for its setting, as described in the opening sentence:

This was in one of those poor London taverns near Clerkenwell, at the sort of hour when taverns are largely empty, and the rare visitors drop in by chance to ask for a mug of beer or a glass of gin. But in one part of a quite dirty room sat several people… (p. 9).

One assumes that Lavrov was therefore familiar with Clerkenwell, possibly from visiting the Patriotic Club, but so far (I haven’t yet had chance to read the whole thing) I’ve come across no further indication of a precise location he had in mind.

The journal may have been growing in circulation, but it was always financially insecure (at one point it was bailed out by Turgenev; Pomper, p. 173), and Smirnov’s determination to keep it going saw him constantly battling against Lavrov’s attempts to stand down. There were also more ideological disputes. The final area of disagreement was over whether the St Petersburg group should have an influence over Vpered! Lavorv, feeling isolated in exile, wished to break away, but Smirnov felt that the journal’s supporters in Russia were crucial and had to be taken into account (Pomper, 195). As a result of this split, Lavrov moved out of the commune and rented a flat at 21 Alfred Place, near Tottenham Court Road, between Chenies Street and Store Street (Pomper, p. 198). Lavrov was suffering very badly with his nerves by now, and only the peace of the British Museum calmed him (Pomper, p. 199). The journal carried on for a brief spell under Smirnov, but ceased publication in May 1877, and Lavrov left London.

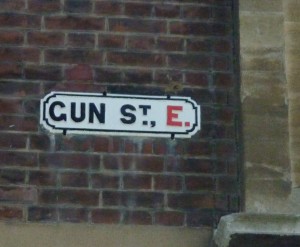

One of the compositors and designers for Vpered! and a member of the commune (who sided with Smirnov in the final dispute; Pomper, p. 195), who also wrote articles for the journal on Russian Jewish affairs (Sapir, pp. 33, 35-43) was Aaron Lieberman, nicknamed ‘Lobster’ (Pomper, p. 174). But Lieberman, originally from Vilno, was much better known as the founder of the first Jewish Socialist Union in London. He arrived in London in the summer of 1875 and sought employment as a teacher at a Jewish school, but was rejected because of his poor English (Fishman, p. 101). Before the end of the year he had joined the commune and was learning how to set type. As Fishman puts it, ‘Lieberman tramped the streets of East London and soaked himself in the atmosphere of the ghetto. Encouraged by Lavrov and Smirnov, he resolved to set up a permanent dual-purpose organisation: to spread socialism and unionise the Jewish workers at the same time’ (p. 103). With Lazar Goldenberg, another Jewish worker on Vpered! (Rocker, p. 54), Lieberman set up a meeting on 20 May 1876 at their friend Leib Wainer’s house at 40 Gun Street, Spitalfields, and the ten men present formed the Hebrew Socialist Union (Fishman, pp. 104). Lavrov and Smirnov were both present at the inaugral meeting (Rocker, p. 54), and the union met 26 times at East End addresses such as 8 Leman Street, and Zetland Hall, Mansell Street, Goodman’s Fields, between then and the end of the year, and had a maximum membership of 40 (Fishman, pp. 104-5). Its aims were mutual aid and education, and its programme was printed in Vpered! no. 37, before being translated into Hebrew and smuggled back into the Pale of Settlement (Fishman, pp. 107-10). Lieberman became unpopular, however, and left London in mid-December 1876; the union held its final meeting shortly after this (Fishman, p. 124).

One of the compositors and designers for Vpered! and a member of the commune (who sided with Smirnov in the final dispute; Pomper, p. 195), who also wrote articles for the journal on Russian Jewish affairs (Sapir, pp. 33, 35-43) was Aaron Lieberman, nicknamed ‘Lobster’ (Pomper, p. 174). But Lieberman, originally from Vilno, was much better known as the founder of the first Jewish Socialist Union in London. He arrived in London in the summer of 1875 and sought employment as a teacher at a Jewish school, but was rejected because of his poor English (Fishman, p. 101). Before the end of the year he had joined the commune and was learning how to set type. As Fishman puts it, ‘Lieberman tramped the streets of East London and soaked himself in the atmosphere of the ghetto. Encouraged by Lavrov and Smirnov, he resolved to set up a permanent dual-purpose organisation: to spread socialism and unionise the Jewish workers at the same time’ (p. 103). With Lazar Goldenberg, another Jewish worker on Vpered! (Rocker, p. 54), Lieberman set up a meeting on 20 May 1876 at their friend Leib Wainer’s house at 40 Gun Street, Spitalfields, and the ten men present formed the Hebrew Socialist Union (Fishman, pp. 104). Lavrov and Smirnov were both present at the inaugral meeting (Rocker, p. 54), and the union met 26 times at East End addresses such as 8 Leman Street, and Zetland Hall, Mansell Street, Goodman’s Fields, between then and the end of the year, and had a maximum membership of 40 (Fishman, pp. 104-5). Its aims were mutual aid and education, and its programme was printed in Vpered! no. 37, before being translated into Hebrew and smuggled back into the Pale of Settlement (Fishman, pp. 107-10). Lieberman became unpopular, however, and left London in mid-December 1876; the union held its final meeting shortly after this (Fishman, p. 124).

The end of Lieberman’s story is not a happy one; arrested in Vienna in February 1878 and, after a long period on remand, tried in Berlin in April 1879, he spent a further 8 months in prison. On his release, he returned to London almost destitute, taking lodgings at 21 Elder Street, Spitalfields (Fishman, pp. 128-9). The house looks smart today, but it was a very poor area, and the unrefurbished house next door reminds us of its humble past. Lieberman continued his propaganda activities, contributing articles on Russia to Johann Most’s London-based newspaper Freiheit, and offered his services to Narodnaia volia (The People’s Will; Fishman, p. 130), but was turned down as unreliable. Whether because of disillusionment with his hopes of contributing to the workers’ cause, as Rocker states (p. 56), or because of an unhappy love affair, as Fishman claims (p. 131), Lieberman left London for New York, and hanged himself in his lodging house in Syracuse on 18 November 1880.

One of Lieberman’s friends in his final months in London was Morris Winchevsky (real name Leopold Benzion Novokhovich), born near Kovno in Lithuania. He had been involved with Jewish socialist groups and publications prior to his arrival in London in 1879, and in 1884 he began the first Yiddish socialist newspaper, Der Poilisher Yidl (Rocker, p. 57). Its offices were at 137 Commercial Street, and the main focus of the paper was on immigrant life and helping newcomers settle in, and it also ‘held a watching brief on rising anti-Semitism’ (Fishman, p. 147). Poilisher Yidl only lasted nine months, but the following year, Winchevsky helped to found the socialist newspaper Arbeter Fraint, later edited by Rudolf Rocker. The new press was set up at 282 City Road, with editorial offices at 29a Fort Street, Spitalfields. The first editor was Philip Kranz, born Jacob Rombro in a stetl in Podolia, Russia. Fishman states that ‘The first editorial sounded the call for a united front of all socialist organisations against the capitalist system’ (p. 152).

Winchevsky was known for writing in a popular, folsky style that appealed to readers (Rocker, p. 57), and this explains his other main claim to fame, as an author of popular Jewish songs. This history is explored in a recent edition of The Cable, and a CD by Klezmer Klub, Whitechapel Mayn Vaytshepl, features some of Winchevsky’s songs. In 1894, Winchevsky, like many Jewish immigrants, left London for New York. Although he continued to work for radical causes, I assume it was his background in popular music rather than anarchist publishing that led to a school and community centre in Toronto being named after him. In any case, the fact that he wore these different hats conjours up a somewhat cuddlier image than East European anarchists usually gained in popular perception at that time.

That popular perception will be the subject of my final post in the series (for now – I will return to the subject later in the year when I’ve had chance to do some more research), as I conclude my consideration of this question of Russian and Jewish radicals by examining two significant incidents.

Sources

The Committee of Delegates of the Russian Socialist Groups in London, An Appeal to Public Opinion: Should the Russian Refugees be Deported? (London: National Labour Press, 1916)

Henry Eaton, ‘Marx and the Russians’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 14.1 (1980), 89-112

William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals, 1875-1914 (London: Duckworth, 1975)

Ben Halpern and Jehuda Reinharz, ‘Nationalism and Jewish Socialism: The Early Years’, Modern Judaism, 8.3 (1988), 217-48

Alan Kimball, ‘The Russian Past and the Socialist Future in the Thought of Peter Lavrov’, Slavic Review, 30.1 (1971), 28-44

Vivi Lachs, ‘Yiddish Song and the Politics of Jewish Prostitution’, The Cable, 14 (2010), 22-4

Philip Pomper, Peter Lavrov and the Russian Revolutionary Movement (Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1972)

Rudolf Rocker, The London Years, trans. Joseph Leftwich (Nottingham: Five Leaves; Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2005)

Boris Sapir, ‘Lieberman et le Socialisme Russe’, International Review for Social History, 3 (1938), 25-88

1 Comment