Now I’ve finished reading Oliver Twist, I can say for certain that the depiction of Fagin is undoubtedly the most problematic aspect of the novel. It is widely known to be a graphic example of anti-Semitism, but even so, it’s quite shocking. I say this as someone who’s used to reading Dostoevsky, but I would suggest that the way Fagin is described is worse than anything we see in Dostoevsky’s fiction (his journalistic work is another matter).

I have to admit I find Dickens’s attitude towards Fagin rather puzzling. Stephen Gill’s introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition (1999) suggests that it was somehow accidental, citing the author’s surprise at later charges of anti-Semitism and his revisions to the text for the 1867 edition, which removed numerous references to Fagin’s Jewishness.

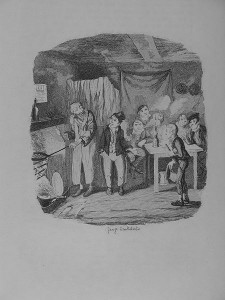

Although I’m very far from being a specialist on Dickens, I’m not convinced. It’s not just the associations with the devil, which begin from the moment he is introduced (and are evident in Cruikshank’s illustration), but the persistence with which Fagin is described as repulsive, ugly, dirty, disgusting, treacherous and evil — it’s pretty much every time he appears. Yes, as Gill states, the stereotype of the Jew as scapegoat was very strong, but Fagin isn’t just scapegoated by society, he’s scapegoated by the text as well. It’s not a commentary on that process, it participates in the process wholeheartedly — not even Bill Sikes, brutal as he is, has anything like the opprobrium heaped on him that Fagin gets. I can’t see any escape from that, and I can’t see that removing a few references to ‘the Jew’ would make that much difference either.

It doesn’t fit with Dickens’s usual sympathy for the marginalized — particularly in a novel which is primarily concerned with denunciation of the poor laws and marginalization/criminalization through poverty. So why is it there? To pander to popular prejudices? To me that seems unlikely; although he was, like Dostoevsky, anxious to maintain his popularity, the social concerns which dominate his novels suggest that his aim was more to undermine, not buttress, the received opinions of the day. In any case, the fact that he takes every opportunity to attack Fagin strikes me as bordering on the obsessive — it feels more fundamental than something intended just to entertain the audience.

Perhaps this is something that cannot be interpreted away, and perhaps we’re all the better for that. It’s often too easy to avoid confronting the most problematic aspects of literature, and the unpleasant attitudes and beliefs of writers whose works we love and (otherwise) respect, but a character like Fagin reminds us that we have to keep on questioning them. Which means I will tackle the complex and extremely unpalatable question of Dostoevsky’s anti-Semitism, and in particular its relationship to his religious faith, very soon.