At my next conference, the 14th International Dostoevsky Symposium, in Napoli this June (volcanic ash cloud permitting), I’ll be presenting a paper on Dostoevsky and the Crystal Palace. It’s a subject that has obviously been examined before, usually in relation to the narrator’s comments in Notes from Underground, but I’ve decided to tackle it partly because my reading has uncovered some features that haven’t really been commented on before, but also because I live in Crystal Palace and have been reading up on the palace itself and the area, exploring the ruins and generally gaining a new perspective. This is a good excuse for me to introduce Crystal Palace as a new theme to my blog, and from now on I will occasionally be writing on that topic, both in its Russian connections and more generally.

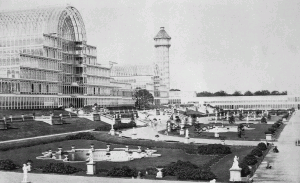

The Crystal Palace was a hugely important image in Russian literature of the mid-nineteenth century, and as part of the process of gathering my thoughts to write my conference paper, I want to start by retracing some of the discussion it provoked, starting with Chernyshevsky’s response. In the July 1854 issue of Fatherland Notes (Otechestevsnnye zapiski) Chernyshevsky wrote a 40-page article, ‘News on literature, art, science and industry’ (compiled from a number of European journals, including The Edinburgh Review, The Illustrated London News, and The Atheneum), half of which is devoted to the opening of the re-built Crystal Palace at Sydenham (the rest, dealing with advances in industry and communications leaves you in little doubt that the author considers the Crystal Palace to be the vanguard of progress and modernity).

The review contains lots of detail about the Palace and its construction, is full of facts and figures on its dimensions and cost, and gives a virtual tour of the interior, and a brief description of the grounds. There’s no mistaking the author’s enthusiasm, as he describes the Palace as a ‘miracle of art, beauty and splendour’ (section 7, p. 82). The historic courts particularly capture his imagination to the extent that he sees them as better than the real thing; the Egyptian Court is praised for bringing together different periods of Egyptian culture, so that one gets a view of the whole inaccessible to visitors to Egypt (p. 87), while the Alhambra Court is ‘a true copy of the beautiful original,’ which ‘shines with brightness and clarity of colour; it is a part of the Alhambra of the 15th century of which only a faded shadow survives in Granada’ (p. 88). Leaving aside the fact that this rather contradicts Chernyshevsky’s argument only a year later in The Aesthetic Relation of Art to Reality for the inherent superiority of life over art, it’s hard not to be caught up by his rhetoric as he describes the crowds flocking to the Palace and gardens and emphasizes the unanimity of positive opinion about it (evidently he hadn’t heard what John Ruskin had to say) to posit it as a universal idea: ‘there has not been a single voice that would be raised against the Palace itself, against its idea and its execution’ (p. 94).

At the time of writing, Chernyshevsky hadn’t visited the Crystal Palace, and it’s not entirely clear whether he ever did. He visited London for 5 days in 1859, to meet Herzen, and while it’s hard to imagine he wouldn’t have made the trip down to Sydenham — surely he would have wanted to see the structure on which he’d lavished so much praise — there doesn’t seem to be much evidence of anything he did in London. Most biographers simply tell us that little is known about his visit. Marshall Berman, in All That Is Sold Melts Into Air, has Chernyshevsky glimpsing the Crystal Palace from afar (p. 220), but this looks a bit like artistic licence and there’s no source to back it up. I need to look at Chernyshevsky’s correspondence to see if there’s anything conclusive.

Whether he did or not, the Crystal Palace resurfaces in Vera Pavlovna’s Fourth Dream in What is to be Done? (strangely, this early edition has had Vera’s dream cut out; the Russian is available here):

Здание, громадное, громадное здание, каких теперь лишь по нескольку в самых больших столицах, — или нет, теперь ни одного такого! … Но это здание, — что ж это, какой оно архитектуры? Теперь нет такой; нет, уж есть один намек на нее, — дворец, который стоит на Сайденгамском холме: чугун и стекло, чугун и стекло — только.

A building, a huge, huge building, such as only exists in a few of the biggest capitals — or rather, no, there’s no other building like it! … But this building — what on earth is it? What style of architecture? There’s nothing like it now; no, there is already one that hints at it – the palace that stands on Sydenham Hill: cast iron and glass, glass and cast iron — nothing else. (Chapter 4.xvi.8)

Here the universalizing power of the Palace to which Chernyshevsky referred in his earlier article comes into its own; 99 out of 100 people chose to live in the palaces because it is ‘приятнее и выгоднее’ (‘more pleasant and advantageous’; 4.xvi.9). If you can get over Chernyshevsky’s leaden prose, two features of Vera’s utopia stand out. The first, as Berman notes (p. 244), is that it is rural. The dream opens with lines from a poem by Goethe (‘Wie herrlich leuchtet / Mir die Natur! / Wie glanzt die Sonne! / Wie lacht die Flur!’; ‘How splendid the brightness / Of nature about me! How the sun shines! How the Fields laugh!), and launches into a bucolic description which comes as something of a surprise in so urban a book:

Золотистым отливом сияет нива; покрыто цветами поле, развертываются сотни, тысячи цветов на кустарнике, опоясывающем поле, зеленеет и шепчет подымающийся за кустарником лес, и он весь пестреет цветами; аромат несется с нивы, с луга, из кустарника, от наполняющих лес цветов; порхают по веткам птицы, и тысячи голосов несутся от ветвей вместе с ароматом…

The meadow glimmers with a golden tint; the field is covered with flowers, and hundreds, thousands of blossoms spread out on bushes surrounding the field, the forest that towers behind the bushes grows green, whispers, and is speckled with flowers; a fragrance is carried in from the field, the meadow, the bushes, the flowers that fill the forest; birds flutter among the branches, and their thousands of voices float down from the boughs along with the fragrance… (4.xvi)

Although some cities still exist, mainly for practical purposes, the only buildings on show are the crystal palaces dotted around this idyllic landscape, in which the inhabitants live and play, invigorated by their hard but joyful and healthy work (sorry if I sound a bit sceptical).

The second feature is, I think, more interesting: Vera’s utopia is based on an ideal of gender equality. The ‘светлая красавица’ (‘radiant beauty’; 4.xvi.3) who guides her through her vision of past and future shows her a series of women in slavery and semi-slavery; only after the revolution can equality exist, and with it, true beauty and love. This is perhaps no surprise as What is to be Done? as a whole is firmly engaged with the ‘woman question,’ but somehow this aspect of the utopia seems to have got lost.

My original intention was to discuss Dostoevsky’s references to the Crystal Palace as well today, but instead I’m going to come back to that in my next(ish) post, and I’ll think about how the ‘woman question’ fits in there in the mean time.

Alex

/ December 21, 2017I’m about to read all your posts about this. I’m studying Russian literature and this seems like a very accessible way to get introduced to these ideas 🙂